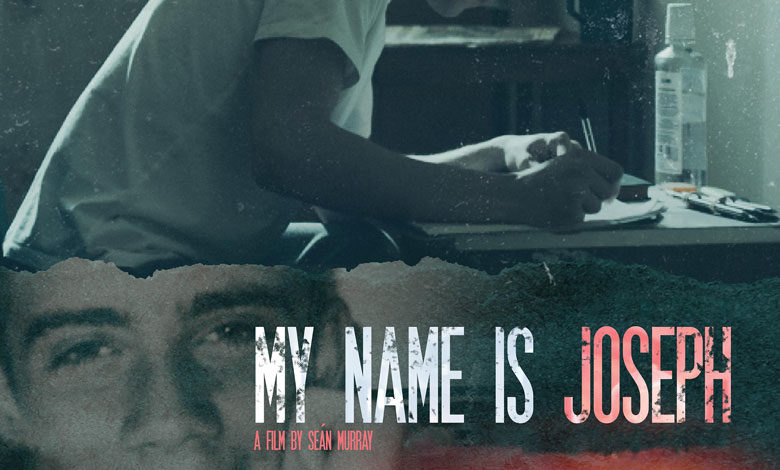

My name is Joseph

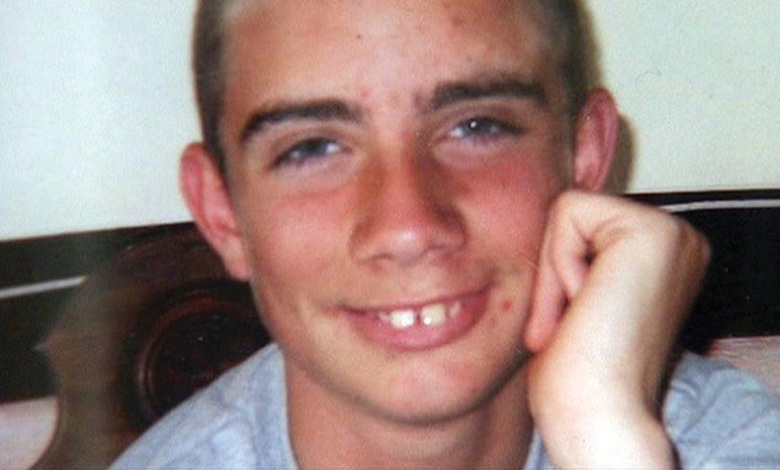

Institutional and systemic failures which contributed to the death in custody of 20-year-old Joseph Rainey are part of a short film by acclaimed director Seán Murray aimed at highlighting the need for cultural change in the Prison Service.

My Name is Joseph, a 12-minute short-film, which recently debuted at the Kerry International Film Festival and won best documentary short, offers an insight into the reality of circumstances leading up to what established authority on social justice, Phil Scraton, described as “one of the most serious inquest verdicts ever seen in Northern Ireland’s history”, given the jury’s severe criticisms of the Prison Service.

Joseph Rainey, a 20-year-old from west Belfast, attempted to take his own life just hours after being received in Hydebank Wood Young Offenders Centre in 2013. He died in hospital 10 days later. In February 2020, a 10-day inquest into the circumstances around his death delivered findings of six institutional failures on transfer to and reception prison; three institutional failures in the healthcare interview on his arrival; and six institutional failures in relation to a lack of care and failure to implement previous recommendations.

In addition, the findings included systemic failures in staff training, suicide awareness, essential documentation, and the observation of prisoners at risk.

The film, which Murray says takes a “warts and all” approach, opens with a scene on 7 April 2013, where an actor playing Joseph can be seen breaking into a shop in Belfast city centre and subsequently being apprehended by police, visibly displaying the anguish that would have come with the realisation that he would face prison for a fourth time in his young life.

What follows is a re-enactment of Joseph’s committal to prison and a harrowing insight into Joseph’s final actions and, most poignantly, missed opportunities for intervention by those responsible for his care.

At the time of his arrest, Joseph’s admission that he suffered from depression and felt suicidal was recorded at Musgrave custody suite and he was deemed not fit for interview until two days later. Following his appearance at Laganside Court, he was sent to Hydebank where documents from the police station confirming Joseph was suicidal were not read. Instead, a reception officer, with no training in suicide awareness, later said he relied on his own observation of new committals, rather than relevant documentation.

When entering the committal landing, the documents were not read again during the committal interview, nor where they passed to healthcare staff, as should have been the case. A nurse initiated a supporting prisoners at risk (SPAR) document when Joseph reported: “Actually I might kill myself with my bed sheets. Despite the Prison Service’s suicide and self-harm prevention policy dictating that a SPaR initiator should remain on duty until a ‘keep safe’ interview was completed, the nurse left the prison and the interview was carried out by an officer with no previous knowledge of the prisoner.

This interview subsequently lasted approximately 70 seconds and less than one hour later, Joseph asked for the Samaritan’s phone number and to be able to make a call, which, after a delay in access, took place and lasted around nine minutes. Shortly afterwards, Joseph is observed writing a letter at a desk in his cell, which would transpire to be his suicide note.

Within three-and-a-half hours, Joseph was found hanging in his cell, having used his bedsheets.

In February 2015, an investigation report by the Police Ombudsman into the circumstances surrounding the death of Joseph identified 15 matters requiring improvement, the majority of which related to poor communication. However, it was highlighted that five of the 14 recommendations had been made and accepted previously by the Northern Ireland Prison Service and the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust, dating back as early as 2008.

At the time the Ombudsman said: “Repeated failure to implement recommendations that have previously been accepted is a matter of concern.”

Worryingly, a similar finding was concluded by the jury in the 2020 inquest into Joseph’s death, advocated for by his family. The jury found that errors or omissions by both the Prison Service and the health trust contributed to Joseph’s death and concluded that recommendations and issues of concern previously raised by the Prison Ombudsman were not actioned by the prison service.

Speaking in My Name is Joseph, Brenda Campbell KC, who represented the family, said a cultural change is required.

“There needs to an appreciation that young people, when they first come into custody are in crisis for one reason or another. They are at their most vulnerable at that moment in time and there has to be a cultural change within prisons broadly, to appreciate that at that point, there is a duty to keep young people safe.”

Discussing the origins of the film, director Seán Murray, says that he hopes the film will not only shine a spotlight on the failings which occurred, but also act as a physical lobbying tool for families demanding change.

Murray, the director of Unquiet Graves, the feature-length documentary investigating the role the British Government played in the Glenanne gang’s murder of over 120 civilians in counties Armagh and Tyrone from July 1972 to 1978, works closely with human rights groups, lawyers, and academics, seeking to “expand marginalised voices”.

He says that as well as serving as a powerful advocate to Joseph’s family, he hoped the film would serve to raise international awareness around the issue.

Following its screening at the Kerry International Film Festival, in My Name is Joseph has also been submitted to the Dublin International Film Festival, as well as film festivals in the likes of France, Finland, Germany and Canada.

“Professor Phil Scraton described the inquest outcome to me as, in his eyes, the most damning verdict for a single case that has ever been seen on record in the North. The magnitude to that is unbelievable,” states Murray.

Murray comes from an academic background, and says that the decision to create a short film was driven by the desire to see the issues within the prison system, particularly for young people, brought to a wider audience.

“I understand that the length of time it takes to investigate and report on these issues is often years in some cases, and often the audience for these findings are within academic, government, or legal circles. A wider audience never sees the case details unless you have a good journalist that can shake these things out, and for me, the medium of documentary brings these issues to a wider audience.”

In the opening scenes of the film, the audience’s first encounter of the case is a hooded Joseph, armed with a crowbar, committing a crime. It is a scene that jars somewhat with the vulnerable young man seen entering prison and reaching out for help, and the person described by his parents as “a real good kid”, who “fell in with the wrong crowd”.

On his decision to open the film in this way, Murray says: “It had to be warts and all. As a filmmaker, you have to adhere to the truth. Joseph tried to break into a shop. The thing is, we stigmatise young people, we label them and there is little empathy for their situation. This film deconstructs that, because it is clear that a lot of these young people are stuck in a cycle. We are quick to blame individuals, but there is a social problem.

Since Joseph’s death, 39 deaths have been recorded in Northern Ireland’s prisons. Inquests have not been held on a number of these deaths in custody, but of those which have, five including Joseph’s have been confirmed as suicide by the coroner from 19 April 2013 to 30 September 2022.

Of those five deaths recorded by the coroner as suicide, two took place within 14 days of committal. For context of the scale of mental health challenges within the prison system, since Joseph’s death, 2,719 individuals have self-harmed in Northern Ireland’s prisons up to 30 September 2022.

Murray describes the failures depicted in My Name is Joseph as “culturally and institutionally, a damning indictment of the prison service”.

On the film’s ability to drive change, Murray concludes: “The film’s appearance at international film festivals will hopefully garner support for the families and raise awareness of the issues that need addressed. However, it also serves as a physical lobbying tool for families. There is an opportunity here to ask those authorities with responsibility for 12 minutes of their time.

“I do not think anyone could watch My Name is Joseph and not sympathise with the families and make a decision that something can be done that might change the culture.”

A spokesperson for the Northern Ireland Prison Service said: “Every death in custody is a tragedy and that is particularly the case when it involves a young person, as was the case with Joseph Rainey. While it will be little comfort to his family, since his death nine years ago, no other prisoner has died in custody at Hydebank Wood and incidents of self-harm have reduced.”

Highlighting that Hydebank has undergone a transition to a “secure college which focuses on rehabilitating the young men in our care through learning and skills”, the Prison Service says improvements since 2013 include:

a Joint Suicide and Self-Harm Risk Management Strategy and a Joint Management of Substance Misuse in Custody Strategy between the Prison Service and the South Eastern Trust;

- a new person-centred approach to Supporting Prisoners at Risk procedures (SPaR)

- the establishment of wellbeing hubs in each of Northern Ireland’s prisons; and

- an increase in Trust staff resources in their mental health teams and a dedicated team is in place in each establishment including a mental health assessment for everyone committed to prison.

The spokesperson concluded: “The Northern Ireland Prison Service is never complacent when it comes to the safety of people in our care and it will continue to review its processes and procedures while working closely with healthcare colleagues in the response to people who self-harm.”