Where have all the workers gone?

Despite a furlough scheme designed to keep employees linked with their employer and prevent high levels of unemployment, a labour shortage is evident in some sectors of the economy. Co-director of the Nevin Economic Research Institute Paul Mac Flynn examines where the workers have gone.

Despite a furlough scheme designed to keep employees linked with their employer and prevent high levels of unemployment, a labour shortage is evident in some sectors of the economy. Co-director of the Nevin Economic Research Institute Paul Mac Flynn examines where the workers have gone.

We are in the midst of one of the most serious economic disruptions since the financial crash of 2008. Skyrocketing energy prices are set to overwhelm businesses and households as we face into many months of double digit inflation. While much of our current predicament can be linked to the geopolitical and humanitarian disaster that is the war in Ukraine, there were serious concerns regarding inflation that predate the outbreak of the conflict.

As the economy eased out from the pandemic, we were facing serious production bottlenecks as supply desperately tried to catch up with a newly resurgent demand. Microchip shortages held up new phones and car sales, while building material shortages sent the cost of construction spiralling.

One of the other significant pressures on the economy was labour. The furlough scheme that was introduced in the UK during the pandemic protected earnings for many workers throughout the crisis. What it also did was it kept people connected to their employer. This was an important design feature of the scheme.

In the Republic of Ireland, many workers became unemployed and were supported through out-of-work benefits rather than remaining on the books with their employer. The thinking behind the furlough scheme was that if workers remained connected to their employer, it would be far easier to start the economy back up once the pandemic danger receded.

That was the plan. However, since the reopening of the economy, we have heard many anecdotes about businesses crying out for workers but unable to fill positions or retain staff. Where have all these workers gone then?

The first thing to say is that there has not been an appreciable drop in the population. The number of people in Northern Ireland and the number of people within that of working age has increased at pretty much the same pace as it did before the pandemic.

The next thing to look at is whether the pandemic dislocated lots of people out of their jobs. The main employment statistics show that the unemployment rate, at 2.6 per cent, is incredibly low by historical standards and close to its pre-pandemic low point of 2.3 per cent. The employment rate has dipped slightly on its pre-pandemic low, but is above the average rate of the previous few years.

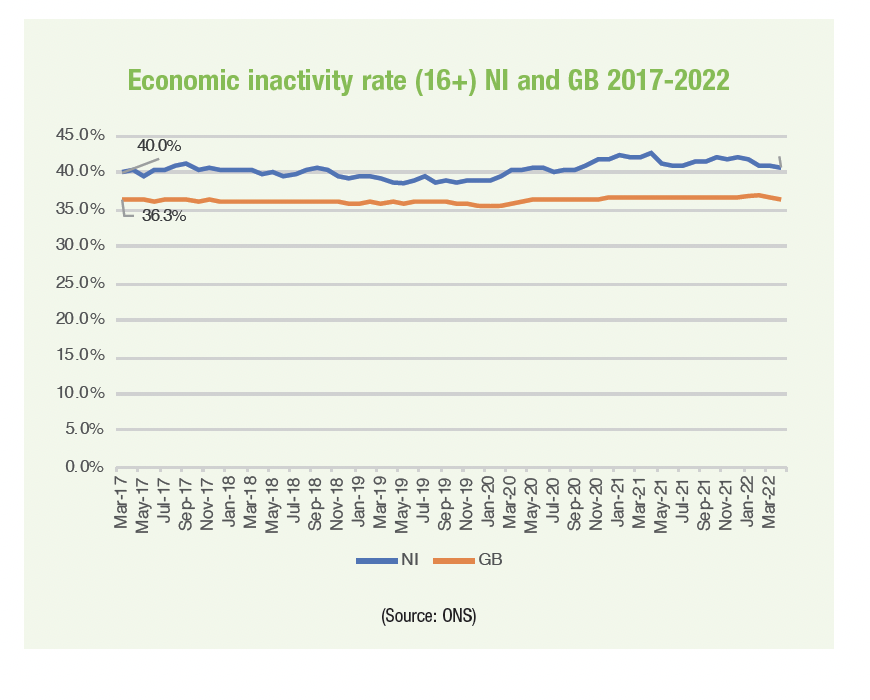

If high levels of unemployment are not what is causing a labour shortage, then perhaps there has been a large exit of workers from the active workforce. In statistical terms we refer to people outside the labour force rather clumsily as ‘economically inactive’. This proposition has gained traction at UK level with many suggesting that the departure of older workers has led to a sudden, and likely enduring, loss to the workforce.

Looking at the figures, we can see that there has been a marked increase in inactivity in both Great Britain and Northern Ireland. However, there are a number of points that need to be considered regarding that increase. Firstly, the increase in inactivity is significant compared with the pre pandemic period, but the current level is not significantly above the average of the last few years. Secondly, in Northern Ireland the increase in inactivity has been spread evenly enough amongst the age groups. In fact, the largest percentage increase was among the 16-24 age group.

The final point to be made is that Northern Ireland has always had an elevated and volatile level of economic inactivity. This has been attributed to many things, but chief among them is a higher level of long-term illness that prevents many potential workers from entering the workforce. So, while we have seen a bigger increase in economic inactivity than Great Britain over the pandemic, the truth is that we have experienced these levels of economic inactivity in the recent past and it has not led to the type of labour shortage we are experiencing now.

Shortage

So, if we do not have masses of people unemployed and if the proportion of workers outside the workforce is only marginally higher, where is this shortage coming from? The next place to look is inside the workforce and the people who are at work. Is it possible that while the number of people at work is not at issue, but where they are working is?

“Hours worked in the economy has still not recovered from the pandemic.”

We may have the same numbers and proportion of people at work, but they may be working in different sectors or industries. When we did start up the economy again, staffing bottlenecks became apparent fairly immediately. Restaurants and the hospitality industry were among the most prominent examples. When we look at the figures though, the number of people employed in the accommodation and food sector is almost identical to what it was before the pandemic. The retail and construction sectors both saw significant reductions in employment in the last two years, but they also saw almost outsized increases in the two years that preceded the pandemic. If anything, the pandemic just evened that out.

So, people moving between industries might explain disruption in some sectors, but not others. As with economic inactivity though, it does not feel like these figures have the necessary scale to really explain why we are seeing such disruption in our labour market.

The last statistic to look at is one that is less reported than the others and that is hours worked. It was a pretty good indicator of the labour market at the start of the pandemic, but since then, we have paid less and less attention to it. Hours worked in the economy has still not recovered from the pandemic.

In April 2022 the total average hours worked in Northern Ireland was 32.8 hours. That is up from a low of 27.4 in April 2020, but well below 33.9 in 2019. The decrease in average hours is almost exclusively confined to full-time workers. Part-timers are working the same hours as they did pre-crisis, whereas full-timers are working an average of two hours less per week.

So, what we can gleam from these statistics is that:

• a certain number of people have left the workforce since the pandemic;

• some sectors have lost and gained employment but others, including hospitality remain the same; and

• the average number of hours worked for full-timers has still not recovered.

A combination of all these effects likely explains our current labour market predicament. What we have to think about is why people leave the workforce or chose to work fewer hours within it. That brings us to other significant labour market issue of our time, pay.

While pay has certainly rebounded since the pandemic, the years that preceded it produced less than impressive wage growth. In order to build a strong and resilient labour force, pay growth and progression needs to be seen as a necessity and not a hindrance.