Union or unity: What does public opinion say?

Jon Tonge of University of Liverpool assesses whether there is evidence of a post-Brexit shift in opinion towards support for a united Ireland.

Since the June 2016 Brexit referendum, there have been 24 opinion polls and surveys asking respondents their views on the constitutional question. What are they saying and how much do such studies matter?

Polls and surveys provide a lot of noise, usually from those liking or disliking the result. For such people, the poll’s validity tends to rest on whether they agree with the headline result, even if their knowledge of weighted quotas, or stratified or random sampling, or indeed any polling methodology whatsoever, is non-existent.

Yet polls and the discussion surrounding them cannot be dismissed as froth. They have the potential to shape constitutional outcomes. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement (GFA) declares:

“The Secretary of State shall exercise the power [to call a referendum] … if at any time it appears likely to him (sic) that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the United Kingdom and form part of a united Ireland.”

There remains a lack of clarity over what evidence the Secretary of State will use to form such a judgement. Attempts to provide any such clarification have fallen on stony ground. Summarising his High Court rejection of such efforts, Mr Justice Girvan insisted:

“The precise circumstances and the political context of a decision are variable and highly political. Decision-making in this area requires a political assessment on the part of the Secretary of State and in this case political flexibility and judgement are called for… I am wholly unpersuaded that the Secretary of State is bound to be bound by a policy detailing the way in which that flexible and politically sensitive power is bound to be exercised. In essence it must be for the Secretary of State to decide what matters should be taken into account on the political question of the appropriateness of a poll.”

Subsequently, the UK Supreme Court refused to hear a case attempting to force the UK Government to publish the criteria. Yet it is difficult to see how anything other than studies of public opinion can be used to provide such criteria. Here though, there are significant differences according to the type of survey conducted.

Of the 24 studies since the Brexit referendum, four have shown more support for a united Ireland than for Northern Ireland remaining in the UK. One, conducted by OFCOC/Deltapoll in September 2018, even gave a united Ireland overall majority support, at 52 per cent compared to 39 per cent for the status quo. Polls conducted by LucidTalk in December 2017 (48 per cent to 45 per cent) and October 2020 (35 per cent to 34 per cent) and a Lord Ashcroft poll in September 2019 (46 per cent to 45 per cent) have indicated a slight favouring for unity but without an overall majority for either constitutional option.

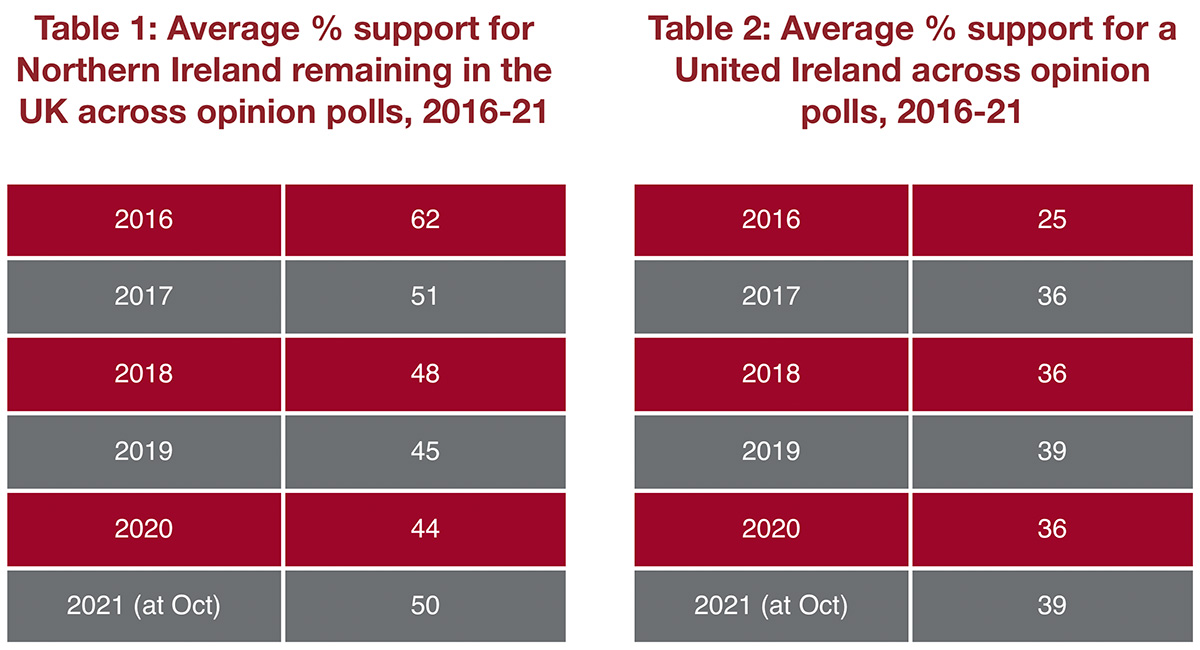

All other studies show more support for Northern Ireland remaining in the UK than for a united Ireland. However, the range is considerable. The highest figure in favour of the constitutional status quo was 63 per cent (Ipsos Mori) in September 2016. From 2016 until 2020 there appeared to be a steady ebbing of support for the union, as the Table 1 annual poll of polls indicates, but this was reversed in 2021. Support for a united Ireland leapt in 2017 but has been steady since. Much caution is needed though as the number of annual polls varies and there are methodological controversies.

The polls have not been bereft of controversy. Support for a united Ireland is invariably higher in online polls than it is in face-to-face surveys. Support for Northern Ireland remaining in the UK is not hugely different between online and face-to-face methods: the difference lies in the figure for support for a united Ireland.

Face-to-face surveys cover the entire electorate, including the one-third of the population who do not normally vote in elections. They find far more ‘don’t knows’ than do online polls, where participants tend to be the already politically committed. The vast bulk of online poll respondents have a firm view on the constitutional future. The united Ireland figure is lower among face-to-face respondents as it is an unknown: many therefore respond ‘don’t know’ although it is a moot point whether they will be converted to the unity project.

Online polls might be criticised as less capable of checking the bona fides of respondents. Face-to-face surveys might inhibit certain responses, including that of support for Irish unity, in front of a stranger from a survey company. Regardless, what matters most is accurate sampling. The Northern Ireland Life and Times face-to-face surveys have been criticised for hugely under-reporting the Sinn Féin vote and as such almost certainly under-reporting support for a united Ireland. Its 2020 survey had the following improbable figures for party support: Alliance 24 per cent, DUP 18 per cent, SDLP 12 per cent, Sinn Féin 10 per cent, UUP 10 per cent.

The near absence of non-voters in online polls is problematic, as some will probably vote in a referendum. Turnout in the GFA referendum, at 81 per cent, was 18 per cent above the general election mean. According to our University of Liverpool study, 31 per cent of non-voters at the 2019 General Election are ‘don’t knows’ on the united Ireland versus UK question, compared to only 7 per cent of voters.

Those ‘don’t knows’ are one set of potential swing voters. Others might be some Alliance voters, 58 per cent of whom said in the 2019 election study that they wanted Northern Ireland to remain in the UK. Some 20 per cent of SDLP voters indicated they would vote for Northern Ireland to remain in the UK, although some were non-natural, tactical voters for the party in 2019.

Controversies over polls and surveys may continue but it is difficult to envisage alternative measures of public opinion beyond elections and the size of support for unionist and nationalist blocs. Since the Good Friday Agreement, they show a decline in support for the unionist bloc (that is, the combined percentage vote share won by unionist parties) from 51 per cent at the last pre-GFA general election in 1997 to 43 per cent in 2019. However, this has not been accompanied by a growth in the nationalist bloc vote, which has remained largely static, at 39 per cent in 2019, compared to 40 per cent in 1997.

In conclusion, the overall picture from polls and surveys is that Northern Ireland remaining in the UK continues to command more support than a united Ireland. In that respect there is no pressure on the Secretary of State to call a border poll. Nonetheless, the prospect of Sinn Féin topping the poll at the looming Assembly election, alongside evidence from the polls that Northern Ireland’s position in the UK merits a bare overall majority of the electorate, means that debates over a border poll – and the significance and veracity of studies of public opinion – will not subside.