UK unplugged?

Chatham House’s Antony Froggatt discusses the impacts of Brexit on energy and climate policy with Owen McQuade during a recent visit to Belfast.

Anthony Froggatt is a senior research fellow at London think tank Chatham House and spoke recently at the Northern Ireland Energy Forum in Belfast. He starts by highlighting the central role the European Union has played in addressing the competiveness, security and climate dimensions of energy policy amongst its member states over the last 30 years. He also details the role the UK has had in driving forward integration of the European energy market, with the UK being a strong advocate of liberalised energy markets and some climate change mitigation policies. This is in the context of the UK being increasingly reliant on imported energy, including from and through Europe, and its energy market is now deeply integrated with that of its European neighbours.

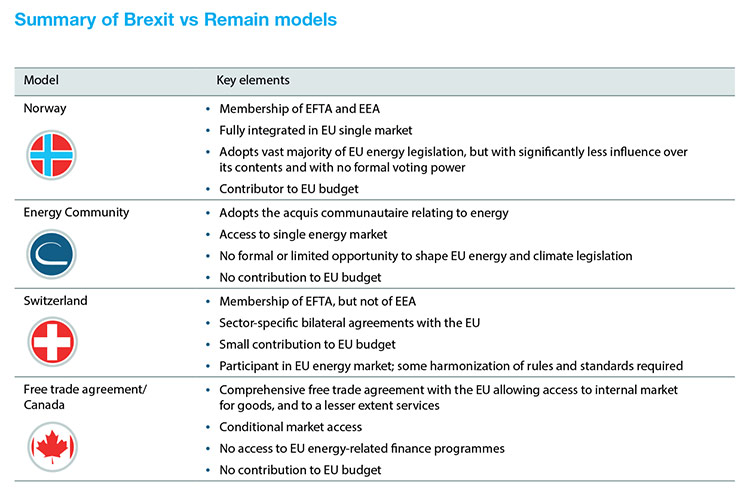

In a report written just before the referendum votes, Froggatt and his colleagues reviewed the risks and trade-offs associated with five possible options for a post-exit relationship between the UK and the EU. The five Brexit models considered were:

1. Norway option (Brexit-light);

2. Swiss option (EFTA not EEA);

3. Free Trade Agreement/Canada option;

4. No deal/WTO option; and

5. Energy Community option.

The report shows the Norway and the Energy Community, which was established in 2005 to integrate the energy market of the 28 member states and eight neighbouring territories, models would be the least disruptive. However, the Energy Community was set up to assist countries whose energy sectors were making the transition towards greater market orientation and therefore membership may not be open to, or appropriate for, a highly developed economy and energy sector such as the UK’s. Both models would enable the UK to continue in energy market access, regulatory frameworks and investment but would come at the cost of accepting the vast majority of legislation whilst giving up any say in its creation.

The Swiss, Canada and WTO models offer the possibility of greater sovereignty in a number of energy policy areas such as buildings and infrastructure standards as well as state aid to the sector. However, all three would entail higher risks with greater uncertainty over market access, investment and electricity prices. These models would reduce or even eliminate the UK’s contribution to the EU budget, but would also limit or cut off access to EU funding mechanisms.

The report makes it clear that all five Brexit models would undermine the UK’s influence in international energy and climate diplomacy. Froggatt argues that although much of the wider European referendum debate has focused on Europe’s influence on the UK, in terms of energy policy the UK plays a key role in the direction in which EU policy is currently moving. “In 2005 there was a real change within UK energy policy towards looking to shape the future energy policy direction of the EU and since then UK policy makers have had a huge influence in terms of energy market liberalisation in Europe.”

“In terms of where European energy policy is going with more renewables and more integration, saying to the UK that we don’t want you to be part of the single European energy market doesn’t make sense but it is caught up in the bigger politics of Brexit.”

An important short-term consequence of Brexit will be the UK no longer holding the Presidency of the EU in the second half of 2017. This will change the political balance within the EU, particularly within the European Council. There are a number of energy and climate policy packages that will be adopted during this period including the climate and transport package, the energy efficiency package and the important renewable energy and market issues package (end 2016). Turning his attention to the 2030 Renewable Energy Directive he says that the UK’s influence has not always been positive. “I would argue that the impact of the UK was to say that we are not going to have binding targets on renewables – it will be binding on the EU as a whole but not on member states.”

Domestic uncertainty

The report concludes that “unplugging from Europe is not an option”. However, since the referendum vote, there has been a change of government ministers and a change in the structure of government departments. This domestic policy volatility has exasperated the uncertainty in the wake of the Brexit vote. Speaking to investors in the energy sector in September, Froggatt says that they were highlighting the fact that they have faced “turmoil” in the energy sector with huge changes in the electricity market over the past 18 months and now they are facing another set of changes on domestic energy policy. This is not perhaps the best environment to attract investment into the sector.

Pragmatically, the UK may still have access to the European energy market. “It doesn’t make sense for any of our neighbouring countries for the UK not to be integrated with them – it is particularly beneficial for the French. But that may not happen because of the bigger politics of Brexit.” When asked could energy be a special case? “Every sector will argue it is a special case. However, I would hope that the Irish Single Electricity Market would be a special case as it doesn’t affect anyone else in Europe.”

The over-arching relationship between the EU and UK will not be determined by the energy sector and there will undoubtedly be unavoidable uncertainty from all the Brexit options over the coming negotiation period that will start once Article 50 is triggered. “The UK has been important in driving much of the European policy on the two key pillars of market liberalisation and climate change. In terms of where European energy policy is going with more renewables and more integration, saying to the UK that we don’t want you to be part of the single European energy market doesn’t make sense but it is caught up in the bigger politics of Brexit,” concludes Froggatt.