Tony Blair on Northern Ireland

Peter Cheney considers what Tony Blair’s biography says about Northern Ireland.

Peter Cheney considers what Tony Blair’s biography says about Northern Ireland.

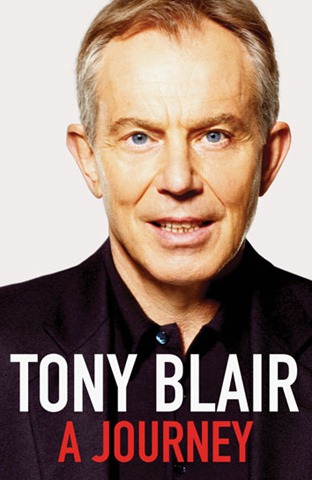

Only five living people know what it’s like to be the UK’s Prime Minister – a fact which in itself makes ‘A Journey’ an intriguing read.

It’s not the first, nor the most comprehensive, book penned about the Blair years so many of the anecdotes are well-known. For an intensively detailed history, read Anthony Seldon’s biographies. But this is the inside story, written in an informal, almost conversational style.

Northern Ireland readers may find the 47 pages on the province predictable as he retells the conflict from scratch. However, all this is necessary for most readers who know little of the “dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone”.

Many compliments are paid, whether to the “extraordinary couple” of Adams and McGuinness, Bertie Ahern, George Mitchell or Sylvia Hermon. Jonathan Powell’s role is highlighted as vital. Sharp criticism is reserved for both sides at Drumcree and how Irish-Americans would “happily raise money used to kill innocent civilians and British soldiers.”

No side could win, but the Republic’s economic transformation, he contends, broke new ground. Ireland was embarrassed by the North and unionists could no longer write off the South.

Truth was stretched “past breaking point”, he openly admits, in many of the peace process decisions. Two murders by the IRA, when apparently on ceasefire, were a “real crisis” but only led to a brief suspension of peace talks. Words were reinterpreted. ‘Side letters’ were written. Deadlines were “always rejected by the parties” but nonetheless progress was made. Ultimately, the governments can claim it was for the greater good.

“We were in a cocoon,” he says of the 1998 talks but this also reflects how most of his time here was spent. Occasionally, he was out and about whether addressing the “ruddy-faced farmers” of Balmoral or being ambushed by “very angry protesting grannies” in the Connswater shopping centre.

He is, at times, cut off from reality. It leads to small, but significant mistakes. His surprise at seeing Palestinian and Israeli flags in Belfast comes as no surprise here; those links go back to the 1970s at least. The two policemen murdered in Lurgan in 1997 were on duty, not off duty.

Small anecdotes are the most interesting parts. The “hand of history” was his own soundbite, with Powell and Campbell cringing in the background. “Some lunatic” chose the austere Castle Buildings as a talks venue which partly explains a preference for stately homes later on.

He ordered the NIO to “raze” the British-Irish office at Maryfield “to the ground”, to please unionists, and adds that “probably everyone forgot about it”. It still stands at 100 Belfast Road, Holywood.

He vividly recalls his great aunt Lizzie’s damp house and mouldy cake in Donegal.

And only Blair can tell his own Irish story. Son of a Donegal-born mother, he learnt to swim, drank his first Guinness and was taught his first guitar chords at Rossnowlagh. The now-converted Blair, grandson of an Orange Grand Master, was warned never to marry a Catholic by his granny. It’s in his blood and it became his driving passion.

His decisions can be questioned but not his commitment. And the Northern Ireland of 2010 is undoubtedly a more peaceful and stable place than it was in 1997.