The UK’s productivity crisis

Chris Giles, economics commentator of the Financial Times, speaks to agendaNi about how the UK’s economic recovery has been hindered by a productivity crisis.

“The UK economy is not in a healthy state, but it is probably not as bad as people outside the UK view it at the moment,” Giles says, summarising developments at the end of 2023.

The most significant problem facing the UK economy, he explains, is a crisis in productivity growth. “Almost every advanced economy around the world has had a decline in productivity growth after the financial crisis of 2008, but the UK’s is bigger than almost anyone else’s,” he says.

The scale of the problem is evident in the challenges posed to forecasting the economic outlook. In April 2008, the IMF predicted growth per annum of about 2.75 per cent out to 2013. In September 2008, the financial crash hit, and since then there has been a gradual but consistent decrease in what economic forecasters think the UK can achieve.

Had the predicted 2.75 per cent growth rate become reality, Giles says that the UK would have a “bright outlook” where public finances would be generating rapid tax revenues with strong real growth. Instead, at 1.5 per cent, “it is tough”, and “if it goes below that, which some people think it will, it is really tough”.

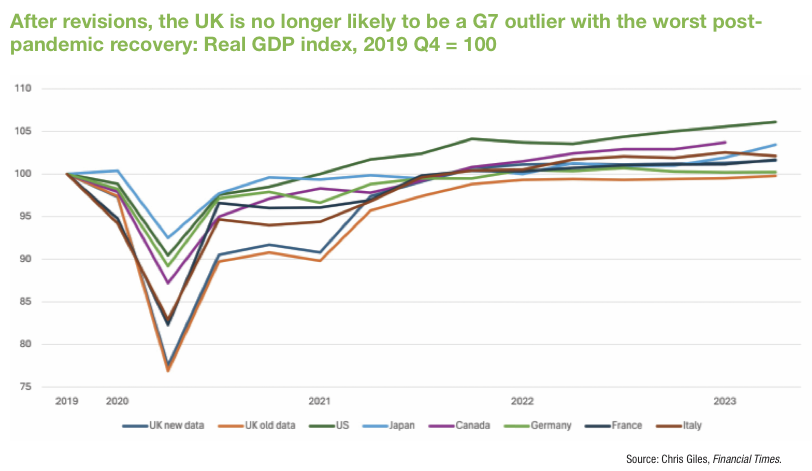

In comparison to the UK, the US has recovered from both the financial crisis of 2008 and more recent economic shocks much faster. Since 2008, the US economy has grown by 30 per cent while the UK’s has grown by 16 per cent, a gap that is mirrored in the recovery figures since the Covid crisis.

While the recovery from Covid-19 has “definitely been [and gone] now”, the UK economy is still between 2 and 3 per cent below “where we thought we would be in 2019” just as Covid began. The crisis led to significant amounts of borrowing, which has left the UK with a debt of roughly 95 per cent of its GDP. With interest rates at 5.25 per cent, such high levels of debt make the debt interest component of government spending significantly higher than previous years.

Inflation

“What has happened in the world in the last year-and-a-half has been the inflation shock, which we are still trying to understand properly,” Giles says. “We are now realising that a lot of it was supply, not demand. There was a demand shock as well, but it was mostly a supply shock, which has now improved and that is helping to bring US inflation down, but US price levels are about 15 per cent higher than they were before the shock, and that is what people feel.”

The inflationary peak was particularly felt in Europe, Giles says, due to the spike in gas prices caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. While gas prices now remain at roughly twice the wholesale price when compared to prices prior to the invasion, they are no longer rising as rapidly as they were in early 2022, with inflation falling to 2.4 per cent in the eurozone, 3 per cent in the US, and 4.6 per cent in the UK.

“We have had a more persistent shock, and this is one thing that the Bank of England is concerned about, that we might have more persistence in our inflation,” Giles says. “I think that is a legitimate concern for now but hopefully that will go away reasonably quickly. The Government can say that they have halved inflation in 2023 although that was always generally going to happen, and the public are unlikely to give the Government credit for that because they will see that prices are 16 per cent higher than they were two years ago and their wages have not risen by 16 per cent, so they are worse off.

“All of this means that people are not happy. The Bank of England is very concerned and has reason to be very concerned. It is an independent, unelected bureaucracy and if it loses public trust, that is a real problem. It has pretty much lost public trust due to this inflation episode and I would have thought that it would absolutely want to have inflation licked before interest rates start coming down. You have to maintain your credibility and central banks have lost quite a bit of credibility over the last year.”

Neither the UK Government nor private sector forecasts predict significant growth in the years ahead, with an average of 1 per cent growth per year predicted over the course of the next five years. This is partly, Giles says, because there is still work to do to lower inflation, with high interest rates designed to “cause some pain” to companies and households and lower spending.

While the Bank of England, the body that essentially controls economic growth through determining interest rates, are pessimistic, Giles believes they are too pessimistic: “Their latest forecast from November 2023 has inflation being more sustained than I think it probably will be, but if they are right, they will need to keep interest rates higher for longer and that will depress the outlook to a point that we will have very little growth over the next few years. The labour market, however, is relatively strong. Employment is not the problem, it is productivity. We have low unemployment and high employment rates, but this is not the problem.”

There are signs for optimism that things may improve earlier than expected, Giles says. Wage growth now outpaces price growth, and business confidence surveys have seen upticks recently, although Giles caveats this by saying they are growing “at quite a low level, but at least going in the right direction”.

Consumer confidence is still low when considered in the long term but has at least begun to recover from its autumn 2022 low point. All of these factors continuing to improve could allow the Bank of England to drop interest rates sooner than expected, which could allow more demand into the economy.

Following a sustained period of economic shocks – from the financial crisis of 2008 to Brexit to Covid and then the inflationary crisis – Giles stresses that the economy could also deteriorate, especially depending upon the result of 2024 US presidential election and the possibility of the latest stage of the Israel-Palestine conflict escalating beyond the Holy Land.

In the UK, public finances improved throughout 2023, with wage growth higher than expected leading to tax revenues also being higher than expected. However, Giles points out that Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt MP’s response to this was not to give the extra revenue to public services, meaning that real increases that were expected in departments are now being replaced by real cuts in government expenditure. “There is something that is going to be very difficult for whoever wins the next election: another period of austerity, or there will be more money put into public services, but then that probably means that the tax cuts we have just been given will be taken back in some other form,” Giles says.

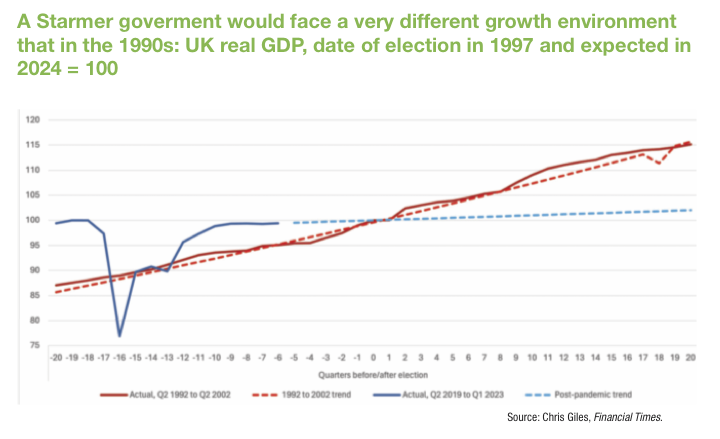

“For Labour, who we expect to win the election given the polls, it is much more difficult than it was in 1997, when they last won an election after a period of being out of power. The other way of looking at it is that they might feel like they have to spend more money but will have to raise taxes as well to fund that.

“It is going to be a tough period, I do not think it is as bad as other countries see the UK at the moment, but it is a pretty sober outlook.”