The state of languages

Language teaching in primary schools “has all but collapsed due to Covid-19”, a 2021 language trend assessment has found.

The finding was part of a wide-ranging survey to assess the current state of language teaching in primary and post-primary schools in Northern Ireland.

Other headline findings included a feeling amongst students of a greater level difficulty in online learning for languages when compared to other subjects, an imbalance between the time grammar schools and secondary schools devote to compulsory language learning and a majority of pupils failing to see languages as part of their future careers.

The Language Trends Northern Ireland 2021 report was carried out by the Director of the Northern Ireland Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research at Queen’s University Belfast and commissioned by the British Council Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland currently has the shortest timeframe for compulsory language learning in any country in the continent of Europe (Key Stage 3, ages 11-14) and there is no guidance from government on how much time should be spent on language learning.

The 2012 Northern Ireland Languages Strategy made 18 main recommendations but to date none have been implemented at a system-wide level.

The 2021 study comes on the back of an inaugural report in 2019 that found 55 per cent of primary schools (surveyed) provided some form of language teaching but that from 2010 to 2018, the number of pupils learning languages at GCSE level had declined by 19 per cent.

The 2021 report acknowledges that the pandemic “brought challenges to language learning at school level unlike anything we could have imagined”. The survey consisted of feedback from a sample of primary school principals, post-primary heads of department and Year 9 pupils.

Post-primary

Over 70 per cent of schools reported some impact on language learning as a result of school closures in January and February 2021. These impacts appeared to disproportionately affect schools where deprivation was greater. More than half of schools in the most deprived category reported a “big impact” compared to just 28 per cent of those classed as least deprived.

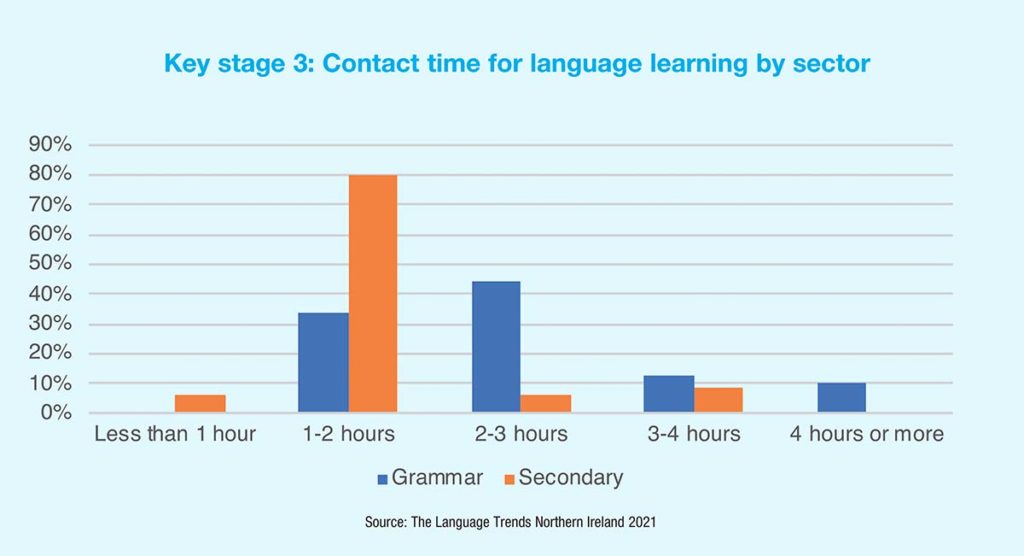

This imbalance continues when considering the time allowed for language learning at Key Stage 3, the compulsory timeframe. Figure 1 shows that grammar schools tended to allow more time for languages than their secondary counterparts in a given week.

In terms of languages on offer, the survey found that French is offered at Key Stage 3 in 90 per cent of responding schools, Spanish in 75 per cent, Irish in 35 per cent and German in 20 per cent.

Interestingly, while over 75 per cent of Year 9 pupils reported to either liking or loving languages, only 44 per cent said they planned to do a language for GCSE and only 10 per cent had plans to do a language for A-level. Potentially telling as to why the drop off rate is so large is a finding that 92 per cent responded negatively when asked how likely it would be that they would use languages in their job upon leaving school.

“This is clear evidence that pupils do not see languages as being part of their careers. There is thus work to be done in helping pupils to see the potential of languages as a career-enhancing skill and to better understand their future self,” the report states.

Key Stage 4

The current Northern Ireland Curriculum provides pupils with the opportunity to continue with a language beyond age 14. A minority of schools retain compulsion as part of their school’s curriculum policy, though this practice is now the exception.

Over half of the responding schools said that 20 per cent or less of their Year 11 cohort was currently studying a language for GCSE or equivalent level 2 qualification. Again, there is a stark contrast between secondary and grammar teaching in this regard. Over 65 per cent of Year 11 pupils is grammar schools are estimated to be taking a language compared to 23 per cent in non-grammar schools.

Overall, more than half of teachers reported that fewer pupils in their school take a language to GCSE than three years ago.

On what languages pupils are choosing to pursue, based on entry data for modern languages at GCSE between 1995 to 2020, the report states: “French has undergone a steep decline since the turn of the millennium; Spanish has grown, albeit from a small base, and is expected to overtake French as the most popular GCSE language within the next couple of years; and Irish and German have both declined overall.”

Languages post-16

Figures attained from heads of departments would suggest that, on average, just three pupils per school in Northern Ireland study languages for A-level

The inaugural Language Trends Northern Ireland report found that from 2010 to 2018, the number of pupils learning languages at A-level fell by 40 per cent for French, 29 per cent for German and six per cent for Spanish. Irish was reported to be stable. Since the last report, entries for French have continued to decline, but Spanish and Irish have both shown some growth.

Barriers to uptake

When asked to identify barriers to uptake across all levels. Teachers gave the following reasons:

- The nature and content of external exams (35.6 per cent).

- The way external exams are marked and graded (26.1 per cent).

- Lack of opportunities for learners to practise their language outside the classroom (14.4 per cent).

- Global English, i.e. the importance of English as a world language (14.4 per cent).

- Timetabling of options in Key Stage 4 (14.1 per cent).

Primary schools

Northern Ireland is the only part of the UK and Ireland where pupils at primary school do not have an entitlement to learn a language as part of the curriculum.

The 2021 study found that just 15 per cent of responding primary schools were teaching a language, compared to 55 per cent in 2019. The report’s authors point out that 38 per cent of respondents point to the pandemic as a reason for temporary suspension of language teaching.

“We can conclude that primary languages are currently in a state of stasis,” state the authors.

Of those schools not teaching languages, over half indicated that they have done so in the past. Lack of funding was listed by over 75 per cent of respondents as the reason for no longer teaching a language, while other curriculum priorities (48.3 per cent), lack of external support/and or teaching resources (48.3 per cent) and no expertise within school (44.8 per cent) were also cited.

Compulsory?

Unlike England, Scotland and Wales, Northern Ireland has not lowered the age at which instructed language learning begins in the last decade.

Interestingly, despite the impact of the pandemic, 70 per cent of primary school principals who responded to the study believe that language learning should be statutory in primary schools in Northern Ireland.

“It is clear from our research that the non-statutory position of languages on the primary curriculum has meant that instructed languages have all but disappeared from participating primary schools due to the Covid-19 pandemic,” the report concludes.

“If languages are to become a part of the curriculum, substantial funding will be required to ensure pupils can make progress. Transition to post-primary language provision will also need to be assured.”

Key statistics

Northern Ireland has the shortest timeframe for compulsory language learning in any country in the continent of Europe

- 19% decline in pupils learning GCSE level languages from 2010–2018

- 92% of pupils responded negatively when asked how likely it would be that they would use languages in their job upon leaving school

- 65% grammar vs 23% non-grammar Year 11 pupils studying a language for GCSE

- 3 pupils per school in Northern Ireland studying languages for A-level

- 70% primary school principals in favour of statutory language learning