The service of last resort

Better data, clear mapping of outcomes and improved collaboration between justice and health are recommended structural changes needed to address the trend of Northern Ireland’s justice system increasingly being used as a service of last resort for people with mental health issues.

In Northern Ireland, one in five people will experience mental health problems in their life, a significantly increased number from even a decade ago. This recognition of more complex and growing mental health issues in society are not only reflected in the criminal justice system but are potentially exacerbated by the system, contributing to reoffending levels.

In Northern Ireland around 24,000 people are convicted of committing a criminal offence each year. Around 3,000 of these receive a custodial sentence and 3,500 are supervised in the community by the Probation Board of Northern Ireland. Recent analysis from the Department of Justice shows that around 41 per cent of those completing a custodial sentence reoffend within one year of release, while 35 per cent of those sentenced to community supervision also reoffend.

Organisations across all stages of the justice system are facing significant pressures as a result of growing mental health needs amongst the general population. This is in part due to the fact that the health system has struggled to deal with this growth, meaning increasing numbers of people are entering the justice system with little to no previous access to necessary health and social services.

A report by the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) analysing mental health in the criminal justice system has outlined the extent to which various organisations are facing increased demands in relation to mental health needs. For example, in policing, the PSNI currently receives over 20,000 reports annually where individuals are experiencing mental health crises but a crime has not necessarily been committed.

While it is true that the overall volume of cases proceeding through the system has decreased over recent years (recorded crimes were down 1 per cent in 2017–18, compared to 2012–13 and police arrests were down 12 per cent in the same period), justice organisations argue that decreasing volumes mask an increasing complexity of needs among those they deal with.

These reports tend to be significantly more complex and time and are being carried out by a police service which has seen its budget cut by some 22 per cent from 2011–12.

A similar pattern is evident throughout the justice system where increasingly complex demands are being dealt with amidst increasing financial pressures. Since 2011–12, all criminal justice organisations have seen significant reductions in their resources including the Department of Justice (42 per cent), PSNI (22 per cent), NIPS (38 per cent) and PBNI (14 per cent).

In Northern Ireland, currently around 64 per cent of people arrested by police are identified, or had previously been identified as having a mental health issue. However, the NIAO report highlights how the “PSNI have found it difficult to implement effective arrangements to ensure effective assessment and provision of necessary health services for these individuals”.

The report identifies the cause of this as a number of structural issues affecting the provision of mental health services across Northern Ireland, drawing attention to the fact that as the health system here has found it challenging to respond to this growth, the justice system is coming into contact with increasing numbers of people who have not been able to access key health and social services that they need.

“Expenditure has not kept pace with demand and individuals can struggle to access the care they need. Where such individuals offend, the justice system can become the service of last resort,” says Comptroller and Auditor General, Kieran Donnelly.

Adding: “The justice system recognises that it has not been able to meet responsibility consistently in a way that supports its wider rehabilitative objectives. The system has found it difficult to evolve in line with the increasing prevalence of mental health issues amongst those it is required to prosecute and rehabilitate.”

As well as the operational complexities of dealing with an individual experiencing a mental health or emotional crisis, the report points to a recognition that for those prosecuted and convicted, the current sentencing framework is generally considered to be “ineffective in supporting rehabilitation”. Key to this consideration is the nature of a high proportion of short custodial sentences, challenges in ensuring the prison system is a safe and healthy environment for those detained and barriers for those exiting the justice system from accessing health and social care services to support continues rehabilitation and resettlement in the community.

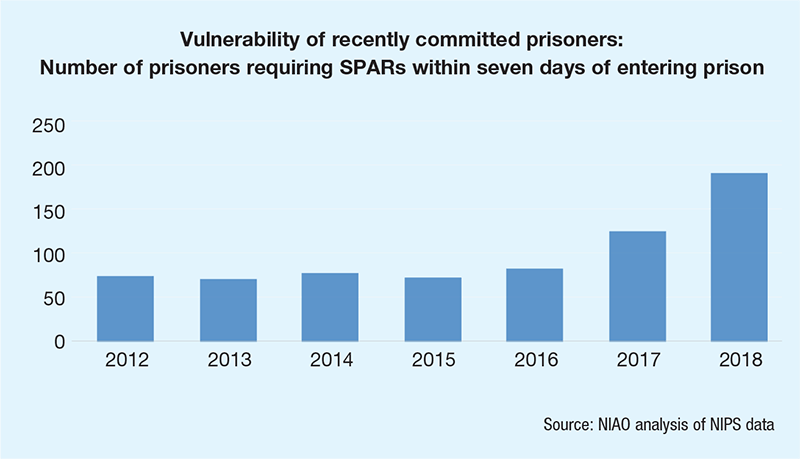

A study by the NIAO of Northern Ireland Prison Service data found that one-third of prisoners between May 2014 and September 2018 reported having already been engaged with mental health service prior to their first night. The increased level of demand being placed on the justice system is evident in the below chart which maps the volume of prisoners needing to be placed in the Supporting Prisoners at Risk (SPAR) programme, part of the NIPS’s suicide and self-harm prevention strategy, within seven days of entering prison.

A similar trend is evident in an increasing number of people leaving prison whilst under a SPAR and currently there is no outreach system for health or social services to help manage the safe return of these individuals to the community. The NIAO report found that within prison, people who require mental health support but who may not be in immediate risk, may have been receiving higher levels of treatment or intervention than would be provided in the community for someone with similar problems.

“Practitioners described prisoners referred for further work after their release being assessed and almost immediately discharged by local community health services as a regular occurrence.”

Reform

Recognition exists that these issues are often compounded by the “disconnected nature of the wider public service network”, and while structural barriers to more effective working practices between justice and health organisations remain, current relationships are positive and contributing to progress.

These include:

- no high level leadership group directing and overseeing implementation of the reform programme as a whole;

- a lack of precision and clarity around what success for the reform programme looks like; and

- the inability of the justice system and its partners to collect enough quality data about mental health and other key vulnerabilities amongst offenders.

To address these, the report recommends a range of measures including the creation of a similar group to the Criminal Justice Board, who have significant potential to overcome general and specific barriers to the development of system-wide responses in relation to justice, to lead on delivering a programme of reforms to improve the justice process for offenders with, mental health issues. It also highlights the need for a framework of shared definitions of key terms and the transparent mapping of outcomes for offenders, believing this will support better management of reform and better communication of progress. Finally, the report outlines the need for the establishment of consistent definitions to support better quality, measurement of issues across individual organisational boundaries and the progress individuals make once they have left the system.

Discussing the reports findings, Kieran Donnelly says: “Justice organisations are increasingly working with individuals with mental health issues who have fallen between the gaps in wider public service. While the justice system is pursuing a range of reform measures to meet this challenge, the evidence to date suggests that more effective co-ordination is required between justice agencies and other key services, particularly health, education and housing services.

“My report recommends stronger cross-departmental leadership, greater clarity and agreement between organisations on what the justice system can and hopes to achieve, and better recording of mental health issues and outcomes for individuals.”