The public arena

Tighter rules on public protests will restrict the quality of democracy, contends John O’Farrell. Politics must be a public activity rather than for private consumption.

Tighter rules on public protests will restrict the quality of democracy, contends John O’Farrell. Politics must be a public activity rather than for private consumption.

These are days in which the political class constantly worry about the viability of their trade. The general election just saw another slide in participation from the electorate in Northern Ireland and few expect next year’s Assembly elections to buck the trend. Oddly, however, the pattern of non-voting stalled in England, widely believed to have been part of the ‘Clegg factor’, as the young felt enthused at the prospect of taking part in a genuine contest rather than a coronation. If that is so, then there are lessons for Northern Ireland.

Here, as elsewhere, political parties have made considerable investments in new technology, in the belief that they can better ‘reach’ the young through Facebook or Twitter than through the traditional routes of newspapers, television or knocking on voters’ doors.

Politics, to have any meaning, should be participatory. People should feel a greater ownership than the right to vote every few years and to spout off on some blog every now and then. Politics needs to be public property; it cannot belong to a minority of specialists, but that is they way we are heading.

The past two decades has seen the emergence of a political class in the truest meaning of the term – we are ruled by people who have done nothing else apart from politics. The Prime Minister, his Deputy, most of the UK Cabinet and all five contenders for the leadership of the Labour Party have never worked at anything else apart from ‘politics’.

This is not a metropolitan disorder. A majority of the Northern Ireland Executive have little or no experience of employment other than ‘politics’. This is even more pronounced among the upcoming generation of MLAs and councillors.

If there was one lesson from the ‘Clegg factor’, it is that the public can get engaged with a politician who seems newer and fresher than the others. Irish Labour leader Eamon Gilmore is currently benefiting from such a bounce. Barack Obama certainly did in 2008. But the voters need more than novelty; they require substance and credibility, intelligence as well as passion. In other words policy matters as much as personality. People will not accept simply being told that there is no alternative to the prevailing wisdom. And they want somewhere to discuss the alternatives.

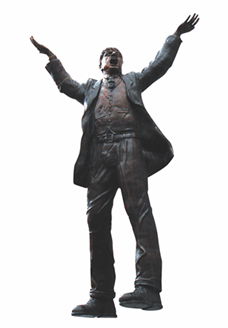

People need and politics requires “a theatre in modern societies in which political participation is enacted through the medium of talk”. A bridge is necessary between the ‘private sphere’ of friends and family and the ‘sphere of public authority’. That space is the ‘public sphere’, defined by the great German philosopher Jurgen Habermas as “the sphere where private people come together as a public.”

“Through the vehicle of public opinion it puts the state in touch with the needs of society,” and it acts “as a regulatory institution against the authority of the state itself.”

Being in public matters. The primary ailment of modern politics has been the effective privatisation of politics itself – the consumer passively reading the views of others in the comfort and isolation of their own home.

This is one of the many reasons why the proposed Public Assemblies, Parades and Protests Bill is wrong. The proposal to implement a uniform requirement for all protests and public exercises in participative democracy marks a further shrinkage of the public sphere. Rallies are meant to stop the traffic – metaphorically speaking at least. They have to be noticed by the public so that they can carry out their educational function, from library closures to May Day to gay pride. And if people object to the latter, they have every right to say so.

Previous legislation marked out the difference between public gatherings and contentious parades. It is disingenuous to suggest that the Public Assemblies Bill is about anything else apart from parades, and a tiny number of those.

Around 1 per cent of all parades and rallies required a determination from the Parades Commission. But to deal properly with these, Sinn Féin and the DUP would have to confront their core supporters with some uncomfortable facts.

Instead, we have this catch-all exercise in denial which flies in the face of civil liberties and human rights. This society requires an active and robust public sphere, publicly and loudly engaging in politics in shared open spaces.