The productivity problem

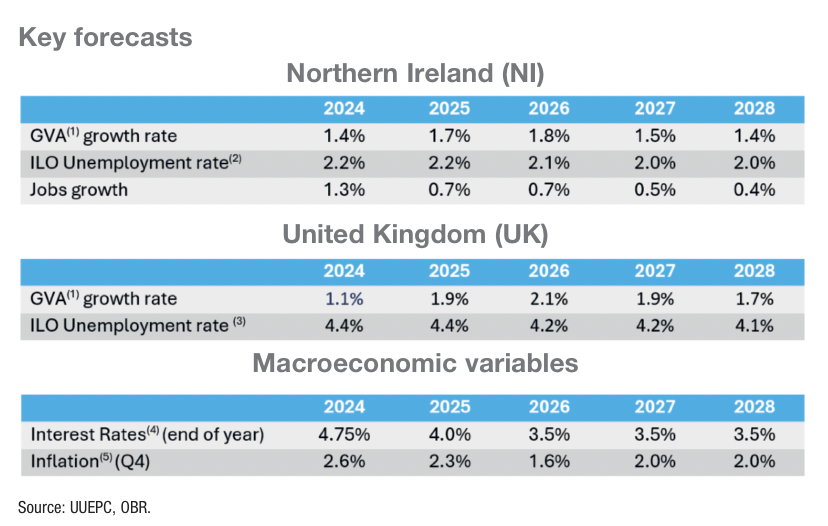

With annual growth of some 1.1 per cent now putting Northern Ireland’s economy 7.6 per cent above pandemic level, signs of improvement are evident. However, short-term growth measurements fail to fully reflect the impact of longstanding structural challenges which have meant little improvement in almost two decades.

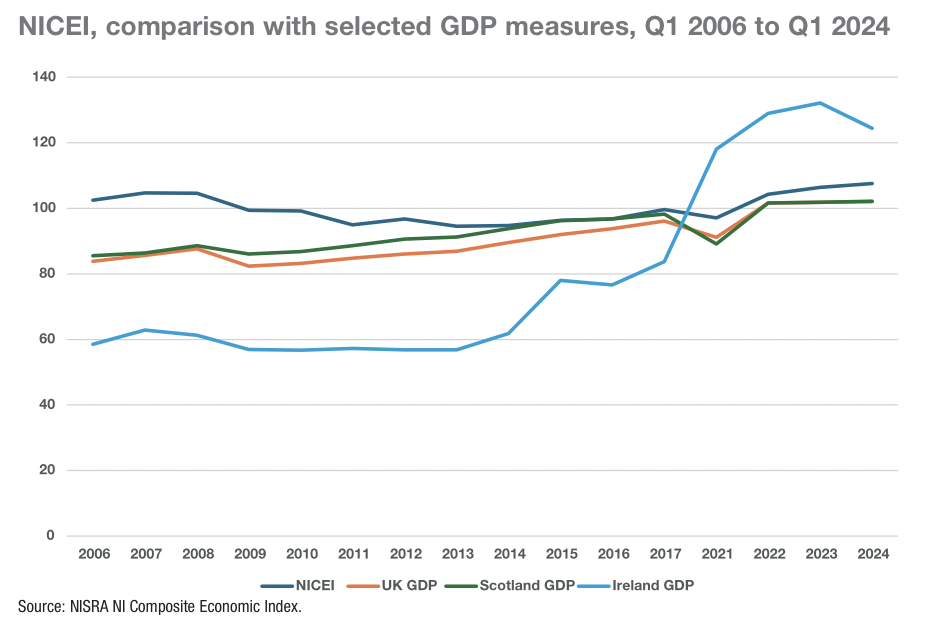

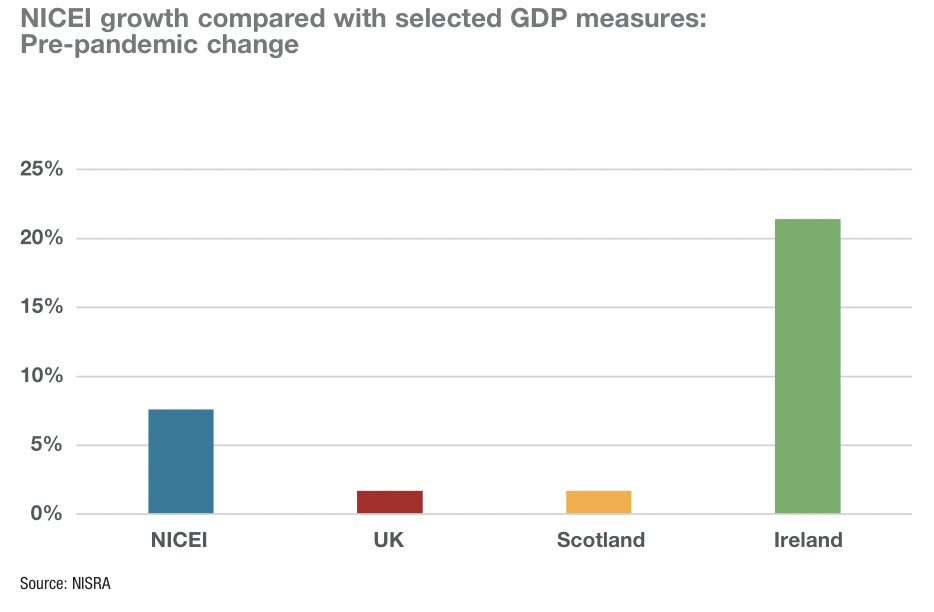

Headline figures suggest that Northern Ireland is on a growth trajectory far greater than that of the UK. An annual increase of 1.1 per cent for Northern Ireland compares to 0.2 per cent for the UK. Similarly, the 7.6 per cent increase from pre-pandemic levels in Northern Ireland compares to a 1.7 per cent GDP improvement for the UK in the same timeframe.

However, what these figures fail to reflect is a larger picture whereby Northern Ireland’s starting point for growth is much lower, thereby exacerbating the scale of percentage point growth. Quarter 2 in 2023 was the first time Northern Ireland’s economy returned to levels last observed at the end of 2007, immediately prior to the financial crash.

Despite itself being a poor performing economy by global comparison (the UK’s real GDP percentage growth from pre-pandemic levels is 2.3 per cent, compared to the 4 per cent eurozone average), the UK economy has recorded GDP growth in 32 of the last 40 quarters of the past decade, compared to the Northern Ireland Composite Economic Index (NICEI) comparison of growth in just 23 of the last 40 quarters.

UK GDP is now estimated to be 16.4 per cent higher compared to its pre-economic downturn peak at the beginning of 2008, compared to Northern Ireland which is now just 2 per cent higher than its 2007 high.

Similarly, comparing the Republic of Ireland’s 5.9 per cent annual decline in economic output to Northern Ireland’s 1.1 per cent increase fails to reflect that the Republic’s GDP is now 21.4 per cent above pre-pandemic levels.

Services

Services make up the majority (52 per cent) of Northern Ireland’s GVA, and a 1.5 per cent annual growth in the sector is a large factor in overall growth across the year. Smaller contributions to growth from the construction (0.4 per cent) and the public sector (0.2 per cent), have offset a decrease in the production sector (-0.6 per cent).

Northern Ireland’s unique market access, including alignment with the EU single market rules for goods, growth in the public sector, which makes up about one-quarter of employment in the region, and the return of an Executive and Assembly in February 2024 are all attributed to recent improved performance.

A prime example of how headline figures for Northern Ireland’s economy often mask long-lasting challenges in the labour market, and in particular, productivity.

Productivity

In August 2024, Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate dropped to a record low of less than 2 per cent. This figure does not reflect the some 320,000 people classified as economically inactive, meaning they are neither in employment nor classified as unemployed.

Evidence suggests that Northern Ireland’s employment growth in the past decade has been dominated by growth in low productivity areas. The UUEPC estimates that 73 per cent of employment expansion between 2013 and 2023 was in sectors with ‘below-average wages’.

“The greater employment increase in below average productivity sectors has resulted in low overall average wage growth,” it states.

Importantly, while Northern Ireland continues to record a steady annual increase in the total number of hours worked since the pandemic, the overall figure remains 0.6 per cent below the pre-pandemic position recorded in October-December 2019.

The UUEPC’s Summer Outlook points to a 5.9 per cent average nominal wage increase for all employees in 2023, building upon similar rises in the two previous years. Despite this, Northern Ireland has the second lowest annual growth rates across all 12 UK regions. When inflation is factored in, average real wages actually declined in 2022 and 2023, meaning that real wages have only increased by 0.6 per cent in the decade to 2023.

Productivity is a key driver of higher wages and better living standards, however, recent data suggests that Northern Ireland is 11 per cent below the UK productivity average, which itself is 8 per cent below the productivity rate recorded for the Republic of Ireland.

Looking deeper, productivity challenges are complex. Existing and future reliance on migration for labour supply are limited by existing and potential future immigration rules. Added to this is existing disparity in the labour market, employment rates in the most deprived areas of Northern Ireland are significantly lower in the least deprived areas. It is estimated that if the employment rate in Northern Ireland’s most deprived areas was increased to match the Northern Ireland average, there would be almost 29,000 more people in employment – equivalent to more than 3 per cent of Northern Ireland’s GDP.

Education

Northern Ireland’s education system has also been linked to historic levels of low productivity. The continued use of academic selection in some schools in Northern Ireland has been linked to poor educational outcomes, and the disparity in outcomes depending on socioeconomic background.

In 2022/23, just 56.5 per cent of those entitled to free school meals – a measure of socioeconomic background – achieved at least five GCSEs at grades A*-C or equivalent, including GCSE English and maths, compared to an almost 90 per cent average for the wider school leaver population.

Northern Ireland has the highest proportion of individuals with no or low (NVQ1) skills of any UK region, at almost 20 per cent. While the proportion of those with a tertiary education (NVQ4+) has increased significantly in recent years, Northern Ireland suffers from a documented ‘brain drain’.

A tight labour market, an ageing working population, and a long-standing inability to address structural problems means that even small projected growth in the short term is not necessarily sustainable in the medium to long term. Renewed focus on economic growth driven by the return of the Executive in February 2024 offers a potential change to the economic outlook.