The lost decade

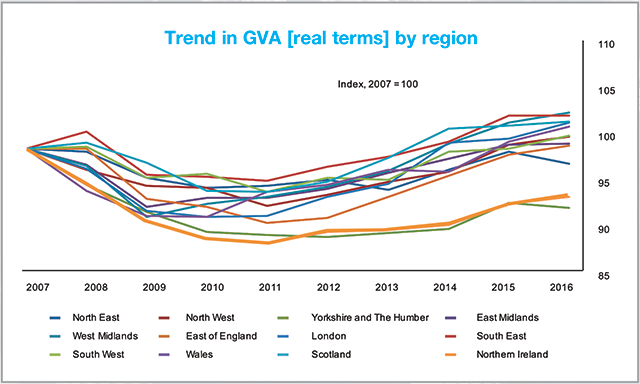

Economic output in Northern Ireland declined sharply with the financial crisis and since then it has flatlined with output in real terms [GVA] failing to recover to pre-crash levels, writes Owen McQuade.

The UK economy as a whole took nearly 10 years to recover from the financial crash. However, the Northern Ireland economy has not yet returned to pre-crash levels. While London’s economy recovered reasonably quickly, and other regions eventually returned to pre-crisis levels, two regions did not, including Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland’s plight is doubly difficult as the region’s GVA per head is 24.1 per cent below that of the UK average (2016). After such a sharp drop and then a decade of stagnation the local economy faces the challenge of Brexit, which will undoubtedly hit core sectors of the economy.

At the helm

Over the last decade, economic policy has been overseen by three DUP ministers. Their collective performance put paid to the DUP’s reputation as being strong on the economy. Arlene Foster served the longest and appeared to have little real understanding of the drivers of the economy. Despite extensive travel her tenure included the failure for nearly seven years to bring a tourism strategy to the Executive. Jonathan Bell’s tenure was particularly non-descript and perhaps the most disappointing performance was from Simon Hamilton. The former accountant said little of substance and had a reputation amongst his officials of avoiding decisions. He achieved little during his tenure. Perhaps the best insight into their collective performance was the RHI fiasco which is now playing out in a very public manner. Whilst much of the media focus has been on the more salacious aspects of the RHI scandal, the failure of the local economy has gone almost unnoticed in the media.

Northern Ireland in context

Looking into the region’s GVA in more detail, Belfast continues to dominate in terms of GVA per capita. The west of the region has lower economic activity than the east and Derry and Strabane is particularly low with the City of Derry not driving the local economy in the same way other cities on the island are driving their local economies.

Over 100 years ago the six counties that comprise Northern Ireland was the economic powerhouse of the island, accounting for 80 per cent of economic activity. Today it accounts for 16 per cent.

The gap in both economies looks set to widen further as the economic growth in the Republic is forecast to continue to significantly outstrip that north of the border. This year’s EY forecast for the Republic of Ireland for this year is 4.9 per cent compared to 1.1 per cent for Northern Ireland. For 2019 the figures are 3.8 per cent for the Republic and 1.2 per cent for Northern Ireland.

Outlook

The outlook for the Northern Ireland economy is for the sluggish growth to continue. The obvious threat of Brexit could see the economy decline sharply and a ‘no deal’ scenario could see a dramatic negative impact. The EY Economic Eye Summer Forecast forecasts 1.1 per cent growth for 2018 and 1.2 per cent for 2019. This is in line with Danske Bank’s 1.0 per cent for this year and 1.2 per cent for 2019.

The Northern Ireland Composite Economic Index (NICEI) for the first quarter of 2018 published by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) highlights the sluggish growth with economic activity estimated to have decreased by 0.3 per cent in real terms between quarter 4 2017 and quarter 1 2018. This decrease was driven by decreases in the construction sector (0.6 per cent decrease) and the public sector (0.2 per cent decrease). These decreases were partially offset by the increase in the services sector (0.4 per cent increase). The lost decade is highlighted in the NICEI, which is currently 6.3 per cent below the quarter 4 2006 value. This is in contrast to the quarter 1 2018 UK GDP which was estimated to have been 10.5 per cent above the pre-economic downturn peak in quarter 1 2008. The latest NICIE results clearly show that, unlike the UK economy, Northern Ireland has had a ‘lost decade’ of economic activity and is in a particularly weak position as it faces the economic uncertainty of Brexit.