The Brexit economy

Owen McQuade looks at the unfolding Brexit chaos and its impact on the Northern Ireland economy.

Despite warnings of a calamitous downturn in the immediate wake of the vote to leave the European Union, the UK economy proved surprisingly resilient in the months after the vote. That all changed over this summer period as the chaos in the UK Government became clear for all to see and the economy began to slow.

Perhaps the most obvious impact of Brexit has been the impact on the sterling-euro exchange rate. At the time of writing in late August the pound was at an eight year low against the euro at just over 92p – some 20 per cent below pre-Brexit levels. Many analysts, including HSBC and Morgan Stanley, are predicting the fall in sterling to continue towards parity with the euro later this year. The immediate impact of the fall in sterling has been the rise in inflation as the UK is a net importer. Consumer prices are expected to rise above three per cent in the near future. Exports have been volatile but export market shares have not risen. This is perhaps a reflection of the steep decline in the UK’s export base over the last 20 years. OECD forecast a 0.1 per cent increase in exports for 2017 and 3.9 per cent increase for imports. The UK has not seen the expected surge in exports from the collapse in sterling.

Slowdown

As 2017 has unfolded GDP forecasts for the UK have continued to be revised downwards in the face of the unfolding uncertainty around Brexit. The last Office of National Statistics (ONS) figures show growth of 0.3 per cent between April and June of this year. However, household spending slumped to a three-year low. Analysts attribute this fall in what is a key driver of the UK economy to the higher inflation figures. This growth figure puts the UK in the laggard position of the G7 economies and has been eclipsed by the 3.8 per cent growth rate forecast [ESRI] for 2017 in the Republic of Ireland.

Wage growth continues to be subdued despite the lowest unemployment rate since 1975. Investment has remained flat and is expected to slow as the Brexit uncertainty continues. The overall figure hides some trends within sectors. For example, in spite of the much heralded Nissan investment, the car manufacturing sector has seen investment drop to a quarter of previous years. This is thought to be the minimum investment to keep the plants going and any more significant investment is in abeyance until the Brexit situation becomes clearer.

The Bank of England will have a real dilemma this Autumn whether to put up interest rates to address growing inflation, against a backdrop of a slowing economy.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland lags the rest of the UK and can expect economic growth of 1.0 per cent in 2017, falling to around 0.9 per cent in 2018 according to a number of analysts. This will make Northern Ireland the lowest amongst the UK regions.

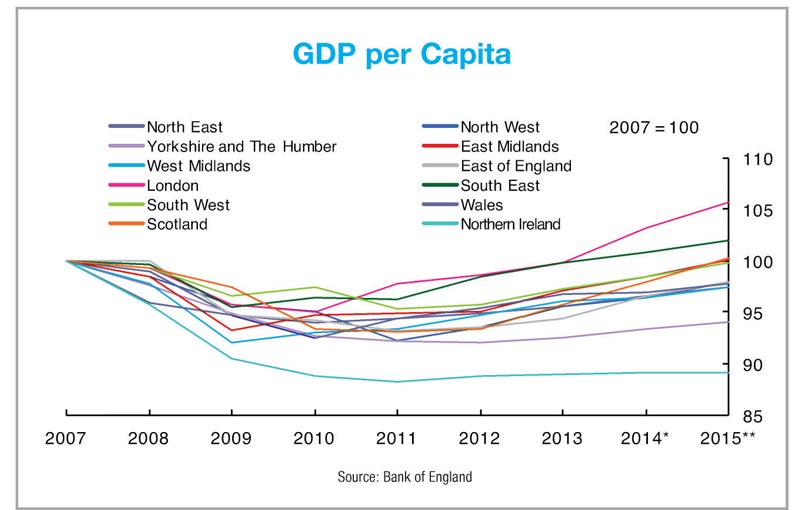

While the ‘confidence and supply’ arrangement between the DUP and the Tories brings an additional £1 billion in new money to the region it will not fundamentally alter the economic performance for the coming year. The deal which brings £200 million a year for two years for infrastructure is welcome but this is dwarfed by the sums involved in the Investment Strategy with runs from 2012 to 2021 and has seen £11 billion already invested and a further £8 billion planned before the end of the plan. The local economy in real terms has not recovered to its 2007 level with GVA in real terms for the region flat-lining since then. This was highlighted in a presentation by the chief economist of the Bank of England in June last year. The Northern Ireland economy is particularly vulnerable to any Brexit downturn.

The recent drop in house prices in Northern Ireland is perhaps another indicator of the economic slowdown in the wake of Brexit. The stalling house prices and the decrease in mortgage applications by nearly 30 per cent on the same period last year are another sign of a slowing economy. Northern Ireland property prices are still significantly behind the pre-recession peak. Brexit will only add further pressures to a slowing economy and two sectors are particularly at risk: agri-food and manufacturing.

Agri-food meltdown

One sector that faces the biggest challenge of Brexit is the agri-food sector. 87 per cent of farm incomes come from farm payments under the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy. This is an astounding figure and one which I felt obliged to go to primary data sources to check when I first came across it some time ago. With its higher ratio of small farms Northern Ireland accounts for nearly 10 per cent of the UK’s CAP subsidy. UK Agriculture Minister Michael Gove is believed to favour using the Barnett Formula to distribute future farm subsidies to the devolved administrations post-Brexit. That would see payments fall to a third of current levels.

One issue that has not got the media attention it should, is the fact that agriculture does not form any part of the single market. Agriculture trade comes under the CAP and is specially excluded. Any trade deal on the single market will therefore exclude agriculture. When it comes to agricultural produce, Europe operates a “Fortress Europe” approach with limited imports of food into the European Union. No country has a comprehensive agricultural trade deal with the EU, something the UK hopes to achieve post-Brexit.

Customs union

The UK Government’s recent policy paper on ‘Future Customs Arrangements’ has been called everything from fantasy to absurd. Reading the paper is puzzling in that it clearly goes against the logic of a customs union: those within the union have common tariffs with those countries outside the union, effectively the union makes the members one whole country from a customs perspective. For the UK to have its own trade deals and tariffs with other countries and yet seek to effectively remain within the European customs union is nonsensical. Striking deals with other countries such as China and India will also open up the UK’s food and manufacturing sectors to cheap imports. Trade deals are two way and many commentators forecast the demise of UK manufacturing and agri-food sectors as a direct result of such trade deals.

Looking to the future it is hard to see any positive economic outlook in the wake of Brexit. Northern Ireland is particularly vulnerable to the UK leaving both the customs union and the single market. Whilst the agri-food and manufacturing sectors look particularly vulnerable the economic impact of Brexit will be felt across many sectors. Indeed it is hard to see any sector being totally immune from the impact of Brexit.