The 2014 centenaries

1914 was one of the most transformative years in Irish and European history. agendaNi recalls the key centenaries to be marked next year.

1914 was one of the most transformative years in Irish and European history. agendaNi recalls the key centenaries to be marked next year.

As 1914 dawned, Ireland appeared to be approaching conflict while most of Europe continued to enjoy peace and stability. The British Government, under Herbert Asquith, was urgently seeking a compromise between unionists and nationalists as Ulster’s opposition to home rule increased. The Ulster Volunteer Force and Irish Volunteer Force had been formed to fight on either side.

By March of that year, the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party had accepted the temporary exclusion (for six years) of part of Ulster from home rule. Each county would hold a referendum: Antrim, Armagh, Down and Londonderry were certain to opt out. Unionist leaders were also keen to secure the exclusion of Tyrone and Fermanagh where unionism held a large minority.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, proposed a military show of strength in Ulster to demonstrate the Government’s resolve. In protest, 58 senior army officers stated on 20 March that they would rather resign than obey those orders. This was termed the Curragh mutiny – although it was not precisely a mutiny because those involved were so senior. The officers backed down when the War Office assured them that political opposition to home rule would not be opposed by force.

The UVF had already imported arms into Ireland in 1913, to resist home rule but royal proclamations in December 1913 outlawed any further imports of arms or ammunition. Fred Crawford, a Belfast businessman and former army officer, won the backing of the Ulster Unionist Council in January to arrange another large shipment.

Purchased through a private arms dealer in Hamburg, these arms amounted to 24,600 rifles and 3 million rounds of ammunition. They were landed on the night of 24-25 April, mainly at Larne but also along the North Down coast, and were rapidly distributed to UVF units. Asquith threatened to bring prosecutions for the gun-running but held back due to the political risks.

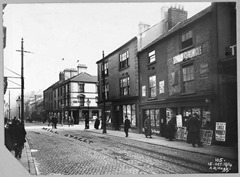

Nationalists were increasingly frustrated by this apparent impunity. Recruitment to the Irish Volunteers rapidly rose and Erskine Childers organised a smaller arms shipment, also from Hamburg. The landing of 1,500 rifles and 45,000 rounds of ammunition took place at Howth on 26 July. Unlike in Larne, policemen and soldiers tried to seize the arms. The troops also opened fire on a rioting crowd at Bachelor’s Walk, killing three.

A spiral of violence appeared inevitable. The Buckingham Palace conference, involving all the key players, had just taken place (21-24 July) but failed to reach agreement on Tyrone and Fermanagh.

Events in Ireland, though, were quickly overshadowed by those in Europe. Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, had been assassinated by a Serbian nationalist in Sarajevo on 28 June. The two countries went to war on 28 July.

Germany sided with Austro-Hungary and Russia with Serbia, thus starting a war between those two major empires on 1 August. Germany then declared war on France (allied to Russia) on 3 August and, in return, Britain (allied to France) went to war against Germany a day later.

Unionism automatically backed the war effort. John Redmond, the nationalist leader, waited until the Home Rule Bill reached the statute book on 18 September. Devolution would be delayed until after the peace treaty was signed and Ulster was still unresolved. Many Irish volunteers joined up but a smaller, more militant group stayed at home and would later fight in 1916.

“Civil war seemed unavoidable, but at the eleventh hour a greater tragedy supervened,” the historian FSL Lyons has recorded. “When the time came to attempt the final settlement the situation over most of Ireland had completely changed.”

In the meantime, by the end of 1914, Ireland was at peace at home yet Europe was now engulfed in – what was by then – the greatest conflict of its history.