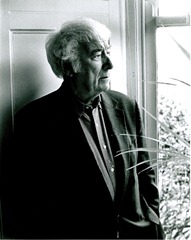

Seamus Heaney: Human Chain

“Mysterious, dream-like markers of the soul” is how Seamus Heaney describes his latest poems. Meadhbh Monahan was in the audience at the Aspects Literature Festival in Bangor when he revealed the thinking behind his most intimate work to date.

“Mysterious, dream-like markers of the soul” is how Seamus Heaney describes his latest poems. Meadhbh Monahan was in the audience at the Aspects Literature Festival in Bangor when he revealed the thinking behind his most intimate work to date.

“Warm hand, hand that I could not feel you lift / And lag in yours throughout that journey / When it lay flop-heavy as a bellpull.”

This is one of the poignant lines written by Seamus Heaney in his poem ‘Chanson d’Adventure’ to describe his trip to hospital with his wife after he had a mild stroke in 2006.

The Nobel laureate’s most recent work, ‘Human Chain’, is his most revealing to date and was part written while Heaney was hospitalised for six weeks, undergoing physiotherapy to regain feeling in his left side.

Dealing with ageing, death and the afterlife, Heaney admits his latest poems are a response to his own experience of ageing and memories of others who grew old and passed away.

It took Heaney around 10 years to accept that he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995.

“The invitations kept coming to the ‘Nobel laureate’ and not to me,” he recalls. Always busy with engagements, university lectures and writing, Heaney decided to keep working despite his “little turn”, and at the age of 71 he is still producing beautiful poetry.

When he was in hospital all engagements were cancelled. Heaney recalls: “There was something terrifically releasing about having nothing on your calendar. I wrote one of my favourite poems in hospital, and when I came out I was alive and free.”

His poem ‘Miracle’ also proved to be the “tuning fork” for the rest of the book. Heaney explains that it is based on the New Testament story of the sick man who is carried by his friends to be cured by Jesus and is lowered through the roof when they can’t get through the crowds.

“The people who don’t get much attention are the friends who carry him,” said Heaney, who was carried to the ambulance by friends and family when he had the stroke.

“Not the one who takes up his bed and walks / But the ones who have known him all along … Be mindful as they stand and wait / For … their slight lightheadedness and incredulity / To pass,” the poem reads. “I realised that these four people were part of the miracle,” Heaney states.

“The human chain is central to our lives and to family life,” he claims. The title ‘Human Chain’ was also inspired by a memory of his then three-year-old daughter saying: “didn’t you and mammy make me and God made the thread?”

Heaney’s father “haunts” the poems on and off. This is particularly apparent in ‘The Butts’. “I realised that the English and Americans [understand this as] the hind end of the human anatomy,” Heaney laughed.

Focusing on finding cigarette butts in his father’s suits which are hanging in a wardrobe, the poem turns into a memory of when Heaney’s father was ill and reads: “And we must learn to reach well in beneath / Each meagre armpit / To lift and sponge him.”

The final poem, ‘A Kite for Aibhín’, was written for the birth of his second grandchild and recalls ‘A Kite for Michael and Christopher’ from his 1984 collection ‘Station Island’. In the latter, Heaney’s young sons are told “you were born fit for it, stand here and take the strain”.

The theme of strain has two important meanings for poets, Heaney claimed. “We begin taking strains musically, waiting for the note that will start us off.” Referring to the “dark times” of the Troubles, he added that “you had to take the strain of what you were living through, that’s the reason for the good heavy-weight poetry in Northern Ireland over the last three decades.”

However, in ‘A Kite of Aibhín’ where “the kite takes off, itself alone” Heaney was focusing on wind as inspiration. It represents the concept of “keeping your feet on the ground while letting your imagination take you.”