Reversing the race to the bottom

Northern Ireland’s productivity doesn’t only rely on resources and investment. It also requires a skilled, stable and motivated workforce, writes economist Paul Mac Flynn.

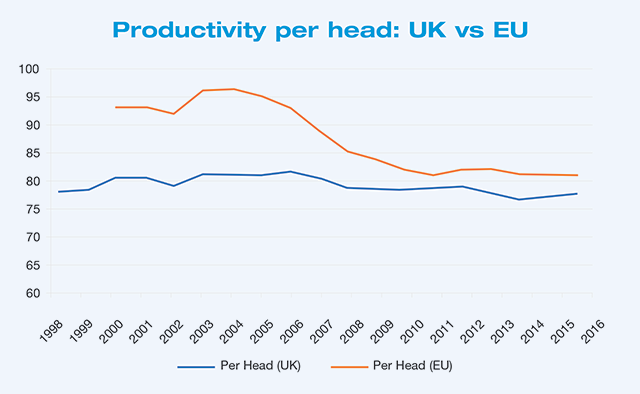

Productivity has become one of the most concerning economic trends facing the Northern Ireland economy for some years now. Employment in Northern Ireland is at record high levels, but we’re not seeing the growth to match it. Put simply, Northern Ireland appears to be either producing less output with the same resources or the same output with more resources. Either way, the direction of travel is not good. We are falling further behind the other regions of the United Kingdom, which is even more concerning given the fact that the United Kingdom is falling behind nearly all other large, developed economies. The chart (right) shows how output per head in Northern Ireland compares with the UK average and the EU average over the last 20 years.

Northern Ireland has fallen from 81.5 per cent of the UK average in 2006 to 77.6 per cent in 2016, lower than it was in 1997. Most of that drop-off occurred after the financial crisis. More startlingly, when compared with the EU average, Northern Ireland started out in a much better position at the beginning of the last decade and has experienced a sharp and prolonged fall-off in comparative productivity performance since then.

As can be seen in the chart, up until 2008, Northern Ireland had been improving its position. The UK was also performing adequately compared to other G7 economies, but then the financial crash happened. Since then, economists have sought to explain the fall off in productivity growth at UK level as a structural change in the financial sector coupled with a falloff in investment by large companies.

Both of these explanations may have some role in explaining the decline in productivity at UK level, but it’s hard to see how these trends could have impacted Northern Ireland to a greater extent than any other region. While Northern Ireland does have a growing financial sector and some large companies, it seems unlikely that they could explain the scale of our underperformance, particularly since 2008. In order to understand our productivity performance, we have to take a closer look at what else has changed in our economy.

Another key trend that has been observed since the financial crash in 2008 concerns the world of work. We have come to know this trend as the ‘gig economy’, but such a characterisation is actually quite deceptive. When the gig economy is mentioned, people automatically think of Uber and Deliveroo and a form of employment which allows people to pick up work whenever they need it with no strings attached. Sounds great doesn’t it? But the gig economy is merely one face of an increasing trend toward forms of employment which are less secure, less stable and quite possibly less productive.

The seeds of this change lie in a body of research that began in early 1990s known as flexible labour markets theory. It was at a time when many western European economies were experiencing prolonged periods of elevated unemployment. While the US had experienced high unemployment, it did not continue to be as a persistent issue for their economy. Research sought to make a link between the labour market policies of the US and its apparently superior unemployment experience. The US had a much weaker system of employment protections, regulations and rights than existed in many European economies.

Flexible labour markets

It was proposed by some researchers that Europe’s systems of employment protections were now a cause of ‘rigidity’ in the labour market that was preventing the economy from reaching full employment. Regardless of the fact that many of these policies had been instrumental in building up the welfare state that had underpinned and supported the sustained period of growth that had followed the Second World War, they had to go. Illustrious research outfits such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank produced voluminous reports claiming that a more ‘flexible’ labour market would not only reduce unemployment but would also deliver greater economic growth and higher productivity.

This body of research became the basis for numerous recommendations in country reports filed by the IMF and became a necessary component of any support packages they offered. The European Commission also became a giddy advocate for such polices and slowly but surely employee rights, employment regulation and related elements of the welfare state were slowly but surely diluted and then eradicated.

The key problem with flexible labour markets theory is that it was based on some fairly broad assumptions and not a whole lot of empirical evidence. Whilst there is some weak evidence for a correlation between some flexible labour market reforms and decreased unemployment, there is almost no evidence to suggest it leads to superior growth outcomes such as increased productivity.

Workers misled

Furthermore, when the flexible labour markets theory was first put forward, it envisaged flexibility for both the employee and the employer, finding an equilibrium where workers could manage their job around competing family and social demands and employers could optimise talent in their workforce. It didn’t quite work out that way. Instead, the removal of key employment regulations and protections brought ultimate flexibility for employers and insecurity for workers.

Flexible labour markets theory gave birth to zero hours contracts, exclusivity clauses in employment contracts and bogus self-employment. This is why the term ‘gig economy’ can be so misleading. Services such as Deliveroo and Uber like to market themselves as companies which exist to provide flexibility for workers. While it is undeniably true that some workers such as students may value such spontaneity, the truth is that these forms of employment have spread well beyond these types of platform companies to more mainstream employers and beyond casual workers to those who need certainty and security.

It is worth reiterating that flexible forms of employment such as part-time or temporary work are not necessarily bad. Indeed, they provide an avenue into the workforce for many people who would otherwise be constrained from participating. It is the way in which these forms of employment have been used. There is a distinct difference in the quality of jobs which are under these forms of flexible employment compared to the more standard forms of employment that most people enjoy.

It isn’t difficult to see how more flexible forms of employment could be enticing for hyper cost-sensitive employers, but in fact, the evidence suggests that some employers don’t know what’s good for them. Productivity requires investment in resources to boost technology and innovation. It also requires a committed, skilled and stable workforce to make it all come together. It is not difficult to see, therefore, how creating a section of the workforce that is insecure, transient and demotivated may have led to a problem with productivity.

Companies which operate flexible forms of employment tend to have much larger turnovers in staff and suffer from inefficiencies that are created when working relationships and institutional knowledge is regularly depleted. Part-time and temporary workers are less likely to be involved in workplace training and upskilling, constraining efforts toward innovation. Furthermore, these companies also tend to have much higher managerial costs associated with managing a workforce that is constantly in flux.

Flexible labour markets theory has therefore not delivered on its original promise, but it’s also possible that it may have made things significantly worse. In a forthcoming NERI research paper, a sector by sector analysis reveals that key productivity gaps within the Northern Ireland economy can be linked to an increase in one form of flexible employment or another.

The policy implications of this are significant. In terms of productivity we do not just need to be more mindful of where employment is being created in terms of sectors, but also the quality of that employment wherever it is created. Flexible employment can be seen in some of the most productive parts of our economy and it may be constraining growth within those sectors.

Abolishing flexible employment is not the answer. However, the problem we have is that flexibility has become synonymous with insecurity. There is no reason why workers should not have guaranteed or predictable hours in established companies. Regulation should make it clear who is and who is not an employee in order to end bogus self-employment. Recognizing the stabilising role of trade unions in the workplace can help reduce large turnovers in staff.

All of these reforms would help workers but just as importantly they would also help firms. They would create a level playing field and end what has become a senseless and self-defeating race to the bottom in employment standards.