Remote learning: Learning loss

While it is difficult to measure the impact the switch to remote learning has had on children and young people, one evident trend is that those who entered the pandemic with the fewest academic opportunities are on track to exit with the greatest learning loss.

Described as a global experiment, remote education, necessitated by the pandemic, has taken many forms as nations sought to manage the spread of the virus within their own restrictions. Pinpointing the outcomes of remote learning for children and young people has proven difficult when considering the many variables, not least the different lengths of school closures, different delivery methods and differing levels of accessibility.

While it is obvious that remote learning has brought benefits in relation to access to education that would not have existed had schools simply remained closed, the overwhelming indication from research is that remote learning remains a poor substitute for being back in the classroom and that students have paid a heavy price in lost learning.

A common theme emerging from current research is a divide in relation to remote education outcomes.

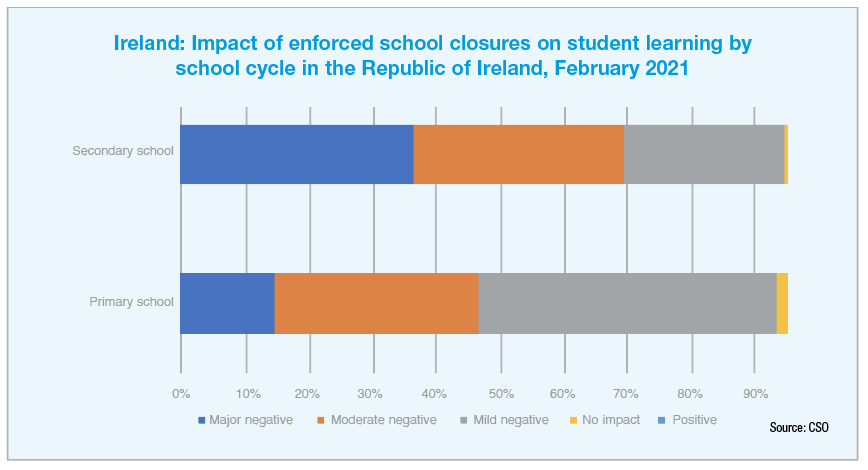

In February 2021, the Republic of Ireland’s Central Statistics Office (CSO) offered some insight into the divide when it published data in relation to the impact of school closures on students’ learning and social development, informed by input of more than 1,600 parents.

The data sought to capture opinions on the different outcomes for different age groups within education. It suggests that the negative impact of school closures is less prevalent when moving down the sliding scale of age groups, for example, almost half of parents with a child in fifth or sixth year of secondary education reported a major negative impact on their learning, compared to just over a third for the whole of secondary education. These figures fell further when assessing the impact of school closures on primary school children, where almost 15 per cent reported a major negative impact.

Looking at it from another perspective, the data outlines that only 9 per cent of parents with a child in fifth or sixth year reported a positive effect of remote education on their child’s learning and this figure fell significantly further for children in junior cycle secondary education, where the rate was just 1.5 per cent.

Disadvantage

However, research carried out globally would suggest the need for closer analysis, not just of the outcomes for children and young people of different ages, but also the impact on the different levels of disadvantage.

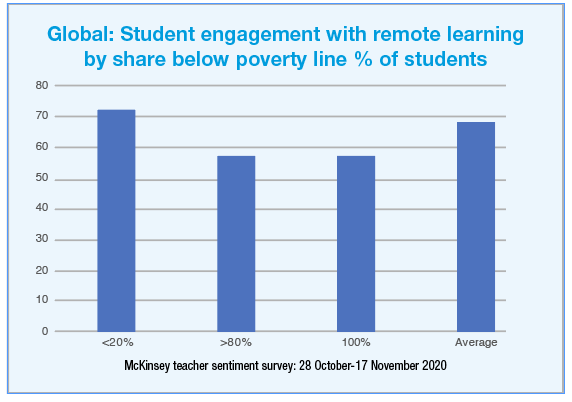

A report by McKinsey and Company has sought to look into the cost of remote working on pupils, with a particular focus on vulnerable students. Unlike the CSO data, the McKinsey report surveyed teachers, recognising their unique viewpoint in “deciphering the long-term impact of this protracted learning experiment”.

UNESCO estimates that by mid-April 2020, 1.6 billion children were no longer being taught in a physical classroom and while it is recognised that many nations used different timelines in relation to school attendance restrictions and that within that there were various models and experiences of remote learning, the broad consensus was that remote learning is a poor substitute for being in the classroom.

Recognising the value of face-to-face learning, amidst the pandemic, The World Health Organization released guidelines which states that school closures should be “considered only if there is no other alternative”.

A trend recognised as a result of teacher feedback from various nations is that while remote learning has improved as schools adopt best practices, it remains difficult for students who struggle with issues such as learning challenges, isolation or lack of resource.

“Teachers in schools where more than 80 per cent of students live in households under the poverty line reported an average of 2.5 months of learning loss, compared with a reported loss of 1.6 months in schools where more than 80 per cent of students live in households above the poverty line,” the report stated.

Although different countries reported different experiences of the effectiveness of instruction once classes went online, one of the most telling trends is an almost universal outcome that teachers in private and wealthy schools are more likely to report effective remote learning, access, and engagement.

In a score out of 10, of the teachers surveyed, those who taught in public schools gave remote learning an average global score of 4.8, which compares to a 6.2 average rating by those who teach in private schools, where it is assumed there is better access to learning tools.

This disadvantage trend is analysed further in assessing the scale of poverty within public schools. Teachers working in high-poverty schools flagged an ineffectiveness of virtual classrooms, rating it just 3.5 out of 10, a finding which feeds into concerns that the pandemic has exacerbated educational inequalities. Teachers in wealthy and private schools reported a much higher rate of students logging in and completing assignments, linked to higher levels of reporting that their students were more likely to report that their students were well equipped with internet access and devices for remote learning.

The report adds: “The full impact of this unprecedented global shift to remote learning will likely play out for years to come. For students who have lacked access to the tools and teachers they need to succeed academically, the results could be devastating.”