Record hospital waiting times

The pre-existing crisis of waiting lists in Northern Ireland has been compounded further by the pandemic. agendaNi assesses the scale of the challenge and the need for dramatic intervention.

Almost 140,000 patients are waiting for a diagnostic service, over 300,000 outpatients are waiting for their first appointments and almost 3,5000 patients were left waiting over 12 hours in emergency departments in March 2021. Northern Ireland’s health system is left with waiting lists that ‘could take 10 years to tackle’.

A governmental target states that at least 75 per cent of patients should be waiting no longer than nine weeks for a diagnostic test. By December 2020, the inverse of the targets, with 75 per cent of patients waiting over nine weeks was closer to being a reality than its achievement. 62.8 per cent of patients, a total of 90,463 were left to wait over nine weeks for a diagnostic service.

None of the health trust areas met the 75 per cent target amongst their own patients, although the location of a patient’s treatment does increase or decrease their chance of having their diagnostic test on time. Patients served by the Western Trust were most likely to be served outside of target times, with only 53.1 per cent of patients seen within nine weeks; patients served by the Southern Trust were most likely to have their diagnostic test on time, with 74.7 per cent happening within nine weeks.

The 62.8 per cent overall rate of those waiting over nine weeks showed a decrease on the quarter ending September 2020, when 65.4 per cent of patients (103,085 in total) were waiting over nine weeks. However, there has been a year-on-year increase, with December 2019 having had a 57.5 per cent rate of these patients (81,286 in total) were waiting over nine weeks for a diagnostic test.

Perhaps even more critical than the missing of the nine-week target is the complete failure to meet the 26-week target that states that no patient should be waiting longer than 26 weeks for a diagnostic test. 40 per cent of patients overall (a total of 57,818) were waiting longer than 26 weeks for a diagnostic test as of 31 December. Again, these figures show a decrease from the quarter ending September 2020, when a 44.8 per cent figure rate meant that 71,968 people were waiting over 26 weeks, and an increase on December 2019 figures, when 30.4 per cent of patients (42,895 in total) were waiting over 26 weeks.

The likelihood of a patient waiting over 26 weeks, again, depended on their trust area, with the rate of the worst performing trust (the Southern Trust, 52.2 per cent) almost double that of the best performing trust (Western Trust, 26.5 per cent). Still, these figures show that a best-case scenario was having an over one-in-four chance of waiting over 26 weeks for a diagnostic test, while the worst-case scenario meant it being more likely than not that a patient would be waiting over 26 weeks.

These quarterly decreases and annual increases in the rates of those waiting for diagnostic tests are reflected in the total number of tests carried out, 361,248 diagnostic tests were reported on in hospitals in Northern Ireland during the quarter ending December 2020, showing a 3.6 per cent increase on the previous quarter, leaving less people waiting. However, a 14.6 per cent decrease on the amount reported on in December 2019 points to the impact that Covid-19 has had on an already strained health system.

Unsurprisingly, attendances at emergency departments began to drop with the outbreak of the pandemic, with attendance figures dropping from 7,571 in February 2020 to 5,909 in March 2020. Following a significant rise during the first reopening of summer 2020, attendance again dropped but has begun to climb again as of March 2021 when 6,438 patients attended Type 1 emergency departments.

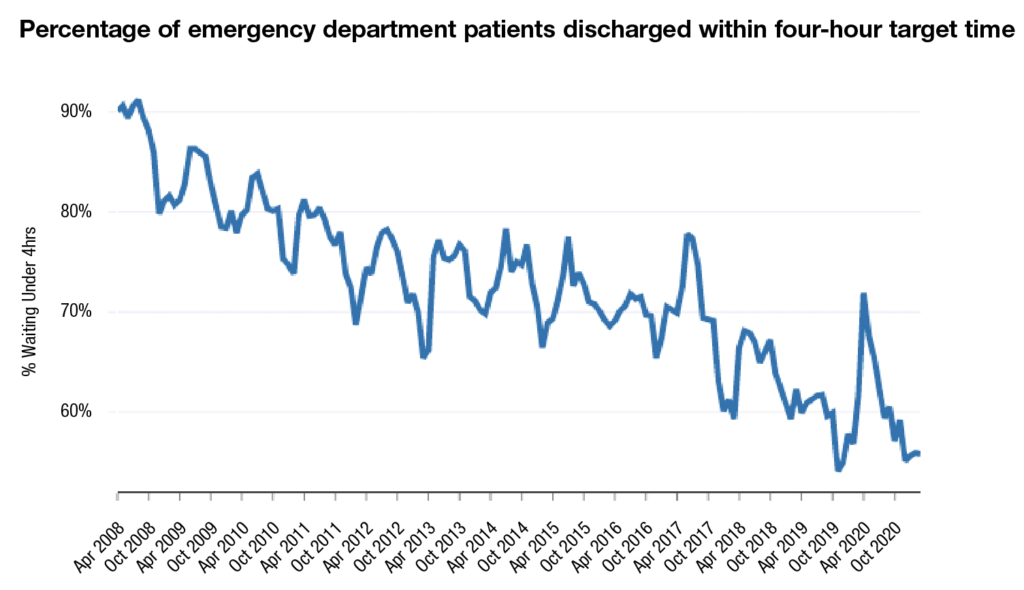

NHS targets state that 95 per cent of patients should be waiting no longer than four hours between arrival and discharge from the emergency department; in March 2021, just 55.8 per cent of patients in Northern Ireland emergency departments were discharged within four hours. While not the lowest rate on record (54.1 per cent in November 2019), the low rate continues a long-term decline that has existed long before the pandemic. Since its peak of 91.2 per cent in August 2008, the rate has steadily nosedived save for yearly recoveries in the summer months. However, each summer recovery tends not to reach the highs of the previous summer, leaving the rate to decrease significantly over time.

The four-hour target is just one indicator of a range of delays and extensive waiting times in emergency departments, with 3,489 patients left waiting over 12 hours to be discharged in March 2021, as few as 20 were forced to wait for such times in 2009.

Outpatients

The overall bleak image of waiting times is not simply confined to hospitals, with numbers of outpatients awaiting their first appointment having increased by 6 per cent year-on-year from December 2019 to December 2020. Like most figures, these show an improvement from the quarter ending September 2020, showing a 1.2 per cent decrease from then. Again, a patient’s location affects their likelihood of waiting, with the Belfast Trust area making up almost one-third (103,836) of those waiting.

Two targets for March 2021 in relation to outpatient treatments are also on course to be missed by significant margins; as of December 2020, 85.3 per cent of patients were waiting longer than nine weeks for their first appointment, significantly higher than the target of no more than 50 per cent; and despite a target of zero patients waiting over 52 weeks by March 2021, there were 167,806 waiting over a year as of December 2020, meaning that one of the few concrete aims within the New Decade, New Approach agreement will most likely not be achieved.

Fully aware of the backlog of patients awaiting treatments across differing categories, Health Minister Robin Swann MLA told the Assembly in April 2021 that people are waiting “too long for treatment”. Following a warning from Department of Health officials that current waiting lists could take between five and 10 years to tackle without adequate finding, Swann told the Assembly that without a joint executive approach, Northern Ireland would be “fighting the scourge of waiting lists with at least one hand tied behind its back”.

Swann stated that the current health funding model is “not fit for purpose”, a sentiment that Finance Minister Conor Murphy MLA expressed in January 2021, when he stated the budget for the forthcoming year was “difficult and effectively a standstill of our 2020-21 budget position”.

The budget published in January 2-21 included a 5.7 per cent increase for health, taking day-to-day spending to £6.5 billion for 2021-22, but the health and social care arms-length bodies leaders stated in their respond to the budget that financial planning was extremely difficult without multi-year budgets and that addressing waiting times will “require significant additional resource and will cost many hundreds of millions of pounds over a number of years”.