Racial equality strategy

Peter Cheney analyses the draft racial equality strategy, which sets out ambitious aims but lacks detail about how they will be achieved.

Peter Cheney analyses the draft racial equality strategy, which sets out ambitious aims but lacks detail about how they will be achieved.

Northern Ireland’s racial equality strategy has finally been published in draft form but contains relatively little detail on how racism will be tackled by government and society. The document was published on 19 June following a series of high profile attacks and Anna Lo’s outspoken criticism of racism in the province. It will run to 2024.

The first racial equality strategy was published by the direct rule administration in July 2005 and covered the five years up to 2010. The current Programme for Government, published in 2012, refers to a racial equality strategy as a ‘building block’ even though the previous version had expired two years previously and a replacement was not yet in place.

All sections of society need to take action against racism, the draft strategy states. Racism in Northern Ireland is partly “shaped by sectarianism” and the department admits that “we cannot hope to tackle one [problem] without tackling the other.”

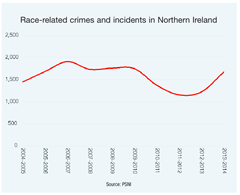

Resentment towards migrants increased alongside the rise in unemployment during the economic downturn. However, the number of racial incidents reported to the PSNI had peaked at 1,908 in 2006-2007 well before the recession began. The number of incidents remained high over the next three years before falling and then rising again to 1,673 in 2013-2014. That increase coincided with a general rise in sectarian tension.

A review by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (February 2013) found that people from ethnic minorities frequently worked in low paid jobs despite many of them having high level skills and qualifications. Others were poorly educated and disproportionally affected by the recession. Poor housing was a regular problem and ethnic minority representatives sensed that there was a “policy vacuum” within government.

OFMDFM’s overall vision is a society in which racial equality and diversity is “supported, understood, valued and respected”. The definition of ethnic minority is extended to cover people from non-Christian faith backgrounds.

Five main aims are set out: the elimination of racial inequality; combating racism and hate crime; equality of service provision; increased participation; and social cohesion.

There has been some pressure for a further aim – to maintain a cultural identity – although OFMDFM is reluctant to take this forward as culture can be expressed in an intolerant way. Officials see a strong case for a separate ‘refugee integration strategy’ but want to assess the level of support for this before formally proposing it.

Guidance on monitoring the effectiveness of racial equality work was published in July 2011 and ethnic monitoring is already carried out by the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. OFMDFM wants more departments and agencies to take this up.

The Prevention of Incitement to Hatred Act (Northern Ireland) 1970 covered incitement on the grounds of colour, race or ethnic or national origins. The Race Relations (Northern Ireland) Order 1997 outlawed racial discrimination in employment, education, goods, facilities and services. Regulations were introduced in 2009 to ban indirect discrimination i.e. actions that would put a person at a disadvantage at some point in the future. Further regulations in 2012 extended existing laws to seafarers, including fishermen.

The Equality Commission wants to strengthen the law against discrimination and harassment carried out by public bodies or by a person’s clients and customers. OFMDFM is asking for the public’s views on whether extra legislation is needed.

The Equality Commission wants to strengthen the law against discrimination and harassment carried out by public bodies or by a person’s clients and customers. OFMDFM is asking for the public’s views on whether extra legislation is needed.

The strategy sets out a broad framework rather than explaining the actions that the Executive will take. OFMDFM will abolish the “very unwieldy” Racial Equality Forum – which now has more than 50 members from different nationalities – and the smaller Racial Equality Panel will draft priorities for the whole Executive. These will go to the OFMDFM ministers for approval but officials warn against drawing up “long lists” of “what we were going to do anyway”.

There is no discussion of the fears and stereotypes which can contribute to racism or how a person with racist attitudes can be encouraged to change them if they wish to do so. The strategy contains several calls for leadership but no agreed summary of the language and conduct which leaders should demonstrate.

OFMDFM allocates £1.1 million per annum to race relations work through its Minority Ethnic Development Fund and there is no clear commitment to increase this funding. Instead, the draft says that “the immediate effect on current funding will be largely neutral”.

The consultation will close on 10 October and will include public meetings in the autumn. In the light of previous delays in OFMDFM’s workload, it is likely that the strategy will be finalised in 2015.

Main ethnic minorities

A total of 32,414 people from non-white backgrounds were recorded in the 2011 census. The largest communities were Chinese (6,303 people), Indian (6,198), African (2,345) and Filipino (2,053).

The national identity question incorporates migrants from white backgrounds. The most common foreign nationality was Polish (18,618 people), followed by Lithuanian (6,590), Indian (2,905) and Slovak (2,375). The census recorded 3,832 Muslims – mainly from South Asia and the Middle East – but the Belfast Islamic Centre estimates that the current number is over 10,000. The difference could be explained by recent migration and a reluctance to state the religion on the census form.