Prisoner Ombudsman: Tom McGonigle

Prior to his pending retirement in May 2017, Prison Ombudsman Tom McGonigle talks to David Whelan about the role of his office and the latest annual report.

In March 2016, the Northern Ireland Assembly passed legislation to support placing the Prisoner Ombudsman for Northern Ireland on a statutory footing. Tom McGonigle believes this is a very positive step but admits that it will not represent a huge change on current operations.

“Right now our basis of operation is in the prison rules and that’s not the proper place to have an independent ombudsman’s office referred to,” he says. “It will give this office statutory authority to enter a prison, to obtain records and to interview staff. The same will apply to the South Eastern Health and Social Care Trust, (who have a responsibility for prison healthcare), for death in custody investigations.

“It’s positive because it clearly spells out the independence of the office from the prison service. We are independent but this makes it clear in legislation and it gives us statutory authority. The reason I say it will not instigate major changes is because the Prison Service has never failed, within my time, to give us anything we have ever asked for. However, this will remove any of those blurred lines around things like access.”

Notably, while the statutory footing will give the Ombudsman greater powers, it does not stretch to including enforcement powers. McGonigle believes that the degree of authority of the office is pitched at the right level under the new legislation. He states that enforcement powers would require a much bigger staffing operation. “We publish annual reports which set out a relatively high uphold rate for complaints, mostly on a procedural basis, and the Trust and Prison Service respond to those, as they do to the deaths in custody reports. There is also a moral imperative on these organisations to apply accepted recommendations. One of our greatest tools is the power of publicity. Engaging with the media in its various forms applies a certain degree of pressure.

“Thankfully we are not dealing with gross violations of human rights, we have a Western, sophisticated prison system. That being said we must never get complacent.”

Complaints

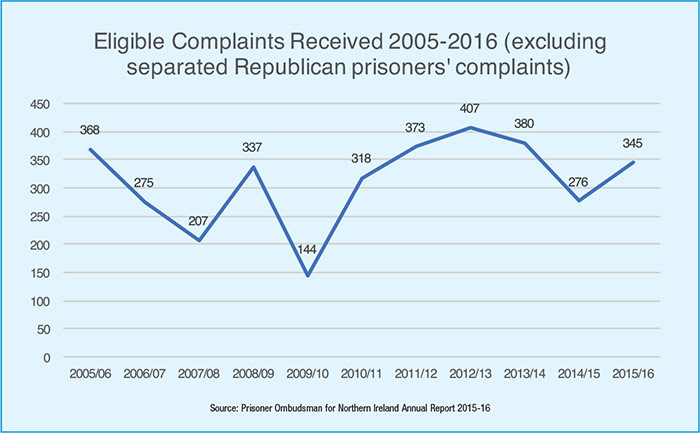

Last year the Prison Ombudsman’s office received 1,593 complaints, around 10 per cent of the total volume of complaints made to the prison service. However, it is noted that around three quarters of all complaints came from separated republican prisoners held on Maghaberry’s Roe 4 landing. Of the complaints made to the office, 41 per cent were upheld.

“A major issue for prisoners evolves around lockdowns. This is a big deal for prisoners and unpredictable lock ups, which can often be based on a staff shortage, give rise to other associated complaints.”

Prisoners or visitors attending Northern Ireland’s jails must first lodge their complaint with the Prison Service and receive a response before the complaint can be passed on to the Ombudsman. Asked whether the high level of complaints upheld reflects a more direct line to the Ombudsman from complainants, McGonigle answers both yes and no.

“No, in so far that any ombudsman system is predicated on the basis that the body against whom the complaint is being made should have a chance to answer first. Yes, in that our operation of a freephone and freepost system already offers the direct line. If a prisoner is not happy with how their complaint is being handled they can lift the phone to us, as they do daily, and it means that no prisoner will have a fear of their complaint being blocked or overlooked.

“As well as that, I am regularly in the prisons and issues raised with me directly or indirectly are forwarded by me to the Governor or to the Director General of the Prison Service. I think the system is as sophisticated as it can be right now. There is simply no perfect way of allowing prisoners independent access, but I think the freephone and freepost system is working well.”

McGonigle points to issues surrounding property and cash, staff attitude and treatment by prison officers being the most frequent of complaints upheld, rather than serious abuses of human rights.

He adds: “We uphold a lot because the Prison Service didn’t adhere to its own policies and procedures. It’s procedural issues mainly, rather than serious human rights abuse concerns. If those concerns were raised I would be going straight to the minister but so far I haven’t had to do that.

“A major issue for prisoners evolves around lockdowns. This is a big deal for prisoners and unpredictable lock ups, which can often be based on a staff shortage, give rise to other associated complaints.”

Prisoner deaths

The issue of appropriate staffing and financial resources also relates to the Ombudsman’s other, and probably most high profile job, of investigating prisoner deaths in custody. McGonigle is clear that his role starts and ends at the prison gates and it is the job of politicians, rather than his office, to decide on the level of finance being put into the penal system.

“Maghaberry is not ‘Dickensian’, I have been in prisons in England and Wales that are considerably more Dickensian.”

Asked whether he believes that financial constraints played a part in a doubling of prison deaths in Northern Ireland in 2016 to six from the previous year, McGonigle is resolute that they did not lead directly to any deaths. “Most of our commentary around deaths in prisons will be about procedural improvements. They might look small, especially in the face of a tragic death, but my attitude is that by attending to them you can start to change the procedural culture.

“Where resources do play a factor is, for instance, the pressure that the Trust are under to see prisoners. Doctors are on a very tight timescale and nurses are stretched dispensing medication and ensuring the prisoners take them. In Northern Ireland we have always invested more in our prison system, we had to because of the Troubles. England and Wales started a programme of cuts around four to five years earlier than Northern Ireland. The situation is considerably worse there where the likelihood of prison mortality is now 45 per cent greater than the general population. I don’t want to see Northern Ireland going the same way.

Speaking about the 2015 Criminal Justice Inspectorate report on Maghaberry, Northern Ireland’s largest prison, which found the internal complaints process was “in disarray”, he agrees that the prison was “not in a good place” at that point in time. However, he also points out that since then the prison has had two much more positive inspections and believes that steps are being taken to mitigate risk.

“Of the three prison establishments here, Hydebank Wood and Magilligan received good inspection reports. Maghaberry was not in a good place at this time but I wouldn’t agree with some of the terminology used in the report. Maghaberry is not ‘Dickensian’, I have been in prisons in England and Wales that are considerably more Dickensian.

“Following the three deaths in November the concerns for me were whether there was a pattern or trend and what could be done to prevent further deaths. Both the Trust and the Prison Service took tangible measures at that time including a consultation action bringing together all stakeholders, while Maghaberry moved around 80 prisoners to Magilligan to counter a steady rise in the prison population and provide better management. That’s what I am looking to see, are they doing all that is possible to minimise the future risk.”

Mental health

Five out of the six deaths last year appeared to have been self-inflicted, though only the Coroner’s inquest can determine a final verdict, and recent statistics, including that around one third of prisoners in Northern Ireland have mental health problems, have raised questions about whether prisons are suitable for dealing with people with mental health problems.

Following three of the deaths in November, Justice Minister Claire Sugden announced a review of services for vulnerable prisoners and talks are ongoing between the Department of Health and the Department of Justice about how to tackle the problem of mental illness in prisons.

McGonigle says: “I certainly see people with serious mental health problems ending up in prison. There has been a steady trend between the psychiatric hospital population going down and the prison population going up. However, it is not my role to comment on the appropriateness of prisoner placement. That is decided by the criminal courts.

“What I will say is that I am delighted that mental health has moved considerably up the agenda.”

Speaking about the challenges for his successor when they take up the reins in the second half of 2017, he said points to ensuring organisation under the proposed new statutory footing. Adding: “I have serious concerns that as the prison population continues to rise steadily, that if mental health problems and the abuse of prescription medication either stay at current levels or increase, in a time of less money for staffing, that we are going to see more deaths in custody.”

“Our prison system is undergoing a generational change in both its prisoner and staff population. There are plenty of challenges and it will always require a strong political system to improve our penal system, if that’s not there then this office will face considerable challenges moving forward.”