Painting history

Peter Cheney explores the Bogside’s famous murals.

Unlike many of Northern Ireland’s murals, those along the gables of Derry’s Rossville Street tell a place’s history rather than taking sides in the Troubles. The work of The Bogside Artists – Tom Kelly, his brother William, and Kevin Hasson – has changed the face of the former trouble-spot over the last 16 years.

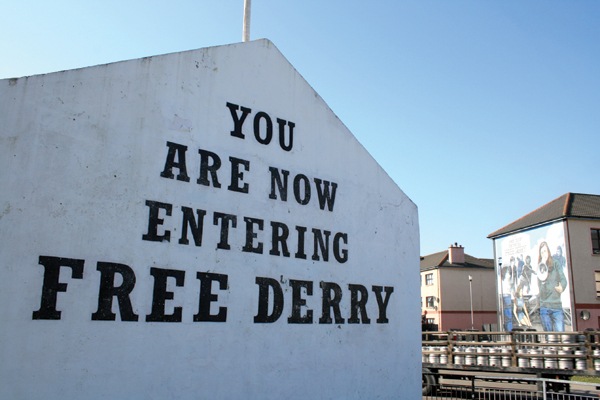

The street was the scene for the Battle of the Bogside, where the Troubles began in August 1969. Free Derry Corner also dates from that time; it was firstly written in graffiti before being properly painted. Bloody Sunday then took place around the same area less than three years later.

“In 1994, we had a vision that we would do a series of murals along the length of Rossville Street in the Bogside. Rossville Street, we would consider in the context of the history of the conflict in Northern Ireland as probably one of the most historical streets,” says Kevin.

The artists have always been first and foremost an arts group, although they have had to paint political content to cover the area’s history properly. They have also been heavily involved in cross-community art work, including painting a Siege of Derry mural in the loyalist Fountain estate at the height of the Troubles.

An 11-year old boy with a gas mask and petrol bomb was the first scene depicted on the street; it was prepared in time for the 25th anniversary of the Battle of the Bogside back in 1994.

Kevin recalls: “The Battle of the Bogside is held in very high esteem in this community, not glorifying violence or celebrating violence, but a lot of people will see that in the community as a moment where, for want of a better word, they made their stand.”

To the artists, the challenge was to see if they could actually do the project on the 30-foot walls. However, they and the local people were pleased with the final outcome.

A lot of previous murals had been “fly-by-night” and linked with paramilitaries. In Kevin’s words, The Bogside Artists are not there to wave anyone’s flag or beat their drum.

“What we set out to do was simply to try and tell the story of this community in a very visual way, not to glorify violence,” he states. All three men lost relatives in the conflict so the subjects have a deep personal meaning for them.

Once the idea to paint along the length of the street was formulated, the artists collected a petition of 2,000 signatures in support. The Housing Executive, in turn, rendered, smoothed and plastered the gables so they could start work.

One mural would be erected each year. The artists would go around with an A4 sketch of the latest addition and show it to local people, asking them to make a contribution if they liked the content. The response was “totally overwhelming” with residents also storing paints in their back gardens and sustaining the men with cups of tea.

In their reconciliation work, the artists knew that sometimes young people from each community went away to workshops but then never saw each other again. They therefore brought the same group of children from Protestant and Catholic areas together over several years, to paint bottles, banners and murals. Some of them went on to forge lasting friendships.

When they reached the far end of the street in 2004, the end result was a peace mural designed by Protestant and Catholic schoolchildren.

“We felt throughout the series of murals that we depicted on the street here telling the story about this community broadly spoke to everyone within nationalism regardless of their own political thinking,” Kevin comments.

Tourists often stop by to view the murals, the French and Italians noting there was nothing like in it their illustrious art history while German and Dutch visitors enquire about planning permission and red tape. Most have made their way from Belfast and remark on .how different the murals look compared to that city’s republican and loyalist ones.

For them, the most powerful is the Death of Innocents, showing 14-year old Annette McGavigan, who was shot dead by the British army in September 1971.

“It’s a mural that’s dedicated to all the young children that has lost their lives in the Northern Ireland conflict whether they were Protestants or Catholic or English or Irish,” Kevin remarks. It was not possible to paint them all as so many young lives had been lost so Annette was used as a symbol.

Her death “sent shockwaves” through the Bogside at a time when the province seemed to spiralling out of control and hers was reportedly the largest funeral in the city’s history. It is also an art piece with global significance as most fatalities in most wars are civilians.

When it was unveiled in 1997, journalists asked why the butterfly on the mural was coloured grey but the plan was to paint it in full colour when “true and lasting peace” came. As they returned to give it that finishing touch three years ago, the street also has something to say about future hopes as well as history.