Nursing and midwifery workforce gaps

Deficiencies in workforce planning for nurses and midwives in Northern Ireland, with vacancies common and growth not meeting demand, expose a sector ill-equipped to meet the exceptional demands of the Covid-19 pandemic or the demands of an increasing and ageing population, according to the Northern Ireland Audit Office.

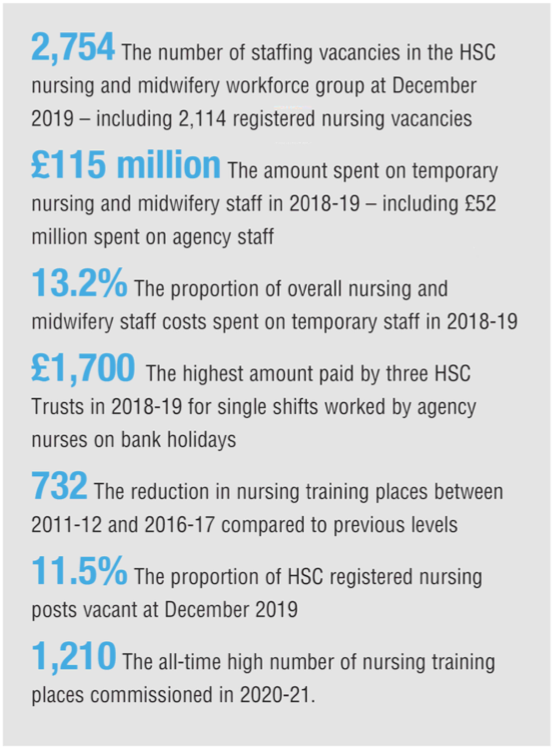

More than one in 10 registered nursing posts in Northern Ireland were found to have been vacant in late 2019 according to the Northern Ireland Audit Office (NIAO) report, with annual spend on temporary nursing staff reaching £115 million by 2018–19, an almost 688 per cent rise on the £14.6 million spent in 2006–07. In that same time period, agency spending has risen almost 523 per cent, from £8.6 million to £52 million, an increase that “has provided particularly poor value for money” according to the report.

The reliance on temporary and agency staff has occurred “against a background of inadequate workforce planning, rising demand for care, high vacancy levels, the need to provide safe staffing levels, and over sickness and maternity absence”. The £115 million spent on temporary and agency nurses and midwives accounts for 13.2 per cent of total staffing costs, which stood at £870 million in 2018-19, a 28 per cent rise from the £680 million spent in 2011-12.

By March 2019, the HSC’s nursing and midwifery workforce group was made up of 22,493 staff or 19,737 whole time equivalent (WTE), with over 16,000 nurses, 1,300 midwives and almost 5,100 nursing and midwifery support staff. The report states that the variance between staff in post numbers and WTE figures are accounted for by the fact that “significant numbers of staff” work “part time to varying degrees”, with 37 per cent of HSC nurses and 63 per cent of midwives registered as part time as of March 2019.

It is in midwifery that the largest challenges appear to be rising for workforce planning in this area. While the number of WTE HSC nurses has increased by 11.7 per cent between 2012 and 2019, and WTE nursing and midwifery support staff increased by 15 per cent in the same period, midwifery WTE fell by 1.1 per cent. Coupled with a workforce comprised of 63 per cent of those in post working some variance of part-time hours, the midwifery stream appears to be the worst affected of the three streams within the sector.

Despite the overall growth in the sector in terms of employment, the report finds the increases to have been “insufficient” in dealing with the increased demand the healthcare system has been put under by a “growing population which is living longer and developing more long-term conditions”. The 8.8 per cent rise in HSC registered nurses from 2012 to 2019 should have been a rise of over 23 per cent, “assuming similar delivery structures”, in order to meet the increased level of demand.

The failure to meet increasing demand is perhaps best illustrated by the more than tripling of total vacancies between 2013 and 2019. Total vacancies rose from 770 to 2,700 in that period, with 2,100 of the December 2019 vacancies made up of registered nursing vacancies, which also goes some way to accounting for the overreliance on temporary and agency staff in the healthcare sector. Between 2014 and 2019, the registered nursing vacancy rate rose from 3.2 per cent to 11.5 per cent, just 1 per cent off one in every eight registered nursing posts being left vacant.

On top of the 2,100 nursing vacancies the report states that a further 1,600 “nurses are required to ensure safe staffing levels” and notes that a “recurrent funding gap of almost £40 million” has made the recruitment required to fill these gaps harder. The temporary and agency staff who are brought in to fill the workforce gaps caused by these vacancies and the lack of funding are said to “incur higher costs than permanent staff, and are less likely to deliver satisfactory patient outcomes”.

The report also states that “some key previous workforce planning decisions have also contributed to the current staffing pressures”, one such example cited is a Departmental Nursing and Midwifery Workforce Review from 2009 to 2013 that recommended that no changes be made to the number of pre-registration nursing training places being commissioned; this review did not consider the impact of the rising demand for care. In the aftermath of this review, funding for these pre-registration nursing was reduced. Having allocated an annual average of £30.1 million for the places between 2009–09 and 2010–11, these figures fell to an annual average of £28.8 million between 2011–12 and 2016–17, which resulted in 732 fewer nursing training places being commissioned during that period when compared to 2009-10 levels.

These cuts occurred at a time when demand continued to rise, with the Department telling the NIAO that the “decision was taken in the face of wider financial and affordability pressures”, but the report finds that the significant and prolonged reduction in training places has had longer-term consequences, including contributing to the rising vacancy levels and increased reliance on more expensive temporary staff”. Funding for post-registration training, which allows for specialisation, was also reduced, falling from almost £9.5 million in 2008-09 and 2009–10 to an annual average of £8 million between 2010–11 and 2018–19.

The Department has recognised these failings in its HSC Workforce Strategy, which is planned out to 2026, and is now following steps to fill the staffing holes according to the NIAO. An updated workforce plan published in 2016 had attempted to tackle the issue of demand outstripping supply but delays in its implementation meant that the number of training places commissioned in 2015–16 and 2016–17 was 129 fewer than recommended. The Department and trusts launched an international recruitment campaign in 2016, with the goal of 622 additional HSC nurses by March 2020.

By March 2020, 504 overseas staff had been secured, 458 of which are still in post, but “stringent requirements for achieving UK nursing registration, and visa criteria meant that substantial delays are common before nurses can commence HSC employment”. In the wake of Covid-19, the Department has begun using web-based interviews in an effort to reach the 622 goal quicker.

The report states: “To date, it is unclear whether the actions taken will effectively align staffing supply with the rising demand. The Department will need to continually monitor the situation to consider what further longer terms action may be necessary.”

In May 2020, Minister for Health Robin Swann announced that funding had been secured for an extra 300 nursing and midwifery undergraduate places, bringing the overall number to a record 1,325. “This was a problem before Covid and will remain so after Covid, however the pandemic has only exacerbated it,” the Minister said. “It is clear that there are no quick fixes, and sustainable multi-year funding is required.”