Northern Ireland’s productivity challenge: Picturing success

Whether the goal is the status quo or constitutional change, raising the game for Northern Ireland’s economy is a necessary and immediate task, writes co-director of the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI), Paul Mac Flynn.

It would not be unfair to say that Northern Ireland has an economy that has never really lived up to expectations. It is consistently ranked as one of the lowest performing regions of the UK and trails the Republic of Ireland by a considerable distance.

This performance was brought to light in the recent debates about Northern Ireland’s constitutional future. In evaluating the prospect of a united Ireland, many point to this gap in performance as an insurmountable barrier to integration, while others see it as a measure of the potential gains from a unified economy.

Many argue that it is the status quo that has brought about this underperformance, while others argue that constitutional change will only degrade the situation further.

All of these opinions are valid. However, what they all have in common is a desire to see Northern Ireland’s economic performance improve. Whether the goal is the status quo or constitutional change, raising the game for Northern Ireland’s economy is a necessary and immediate task.

While there has been much work detailing how the failings of policy and the legacy of the past have brought us to our present circumstances, there has perhaps been less commentary about where exactly we want policy to take us in the future. We all want Northern Ireland’s economy to be successful, so what might that success look like?

A new NERI report seeks to begin that debate by looking at the comparative performance of productivity between Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland and the UK. Looking at the overall gap in performance, but also looking at the sectoral level allows us to see more accurately what the scale of the task will be. Delving down to the sectoral level also allows us to look at issues of structure and what the economy produces along with how it produces it.

Seeing the gaps in productivity levels north-south and east-west reveals the scale of the task at hand. But in which direction should Northern Ireland look for transformation? The answer is not as obvious as the figures would suggest.

While the Republic is clearly the best performing economy, many elements of its performance are simply not realistically replicable in a Northern Ireland context. Seeking to match many of the Republic’s policies, such as low corporation tax, may simply not be feasible or fruitful in the current global economic climate. But equally, the UK has been one of the worst productivity performers of the G7 and hardly a candidate emulation.

The answer may be to seek the best of both worlds. As with the post-Brexit trade arrangements, Northern Ireland should seek to take advantage of convergence possibilities with both economies. In some sectors, there should be no barrier to Northern Ireland converging with the Republic, but in others it may be more realistic to aim for UK levels of productivity. Structural changes also matter and how we apportion resources within our economy will also be key to success.

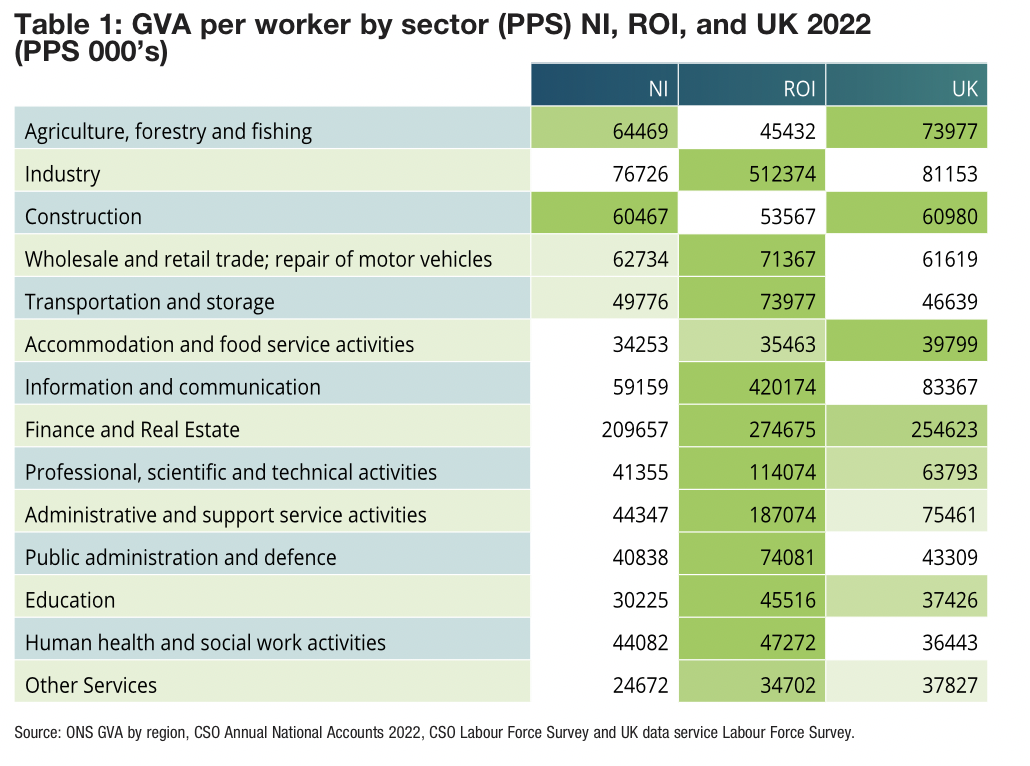

Table 1 sets out the productivity levels (PPP-adjusted gross value added per worker employed) in each sector for Northern Ireland, the Republic, and UK. It shows that in all but three sectors of economic activity, the Republic has the highest productivity performance.

Northern Ireland, compared to the UK and the Republic, does not lead productivity in any sector. It comes ahead of the Republic in construction, while it comes ahead of the UK in health. The UK exceeds the Republic’s performance in agriculture, construction, accommodation and food and other services. The UK also comes close to the Republic’s productivity performance in finance and real estate. The Republic reports very high productivity in industry (which includes manufacturing), administration (which includes the aircraft leasing activities) and information and communication. The three sectors contribute to significantly increasing the Republic’s total productivity performance but are distorted by the relocation of IP assets (and profits) to Ireland. UK output per worker is 42 per cent of the of the Republic, while for Northern Ireland, it is 36 per cent of total Republic of Ireland productivity.

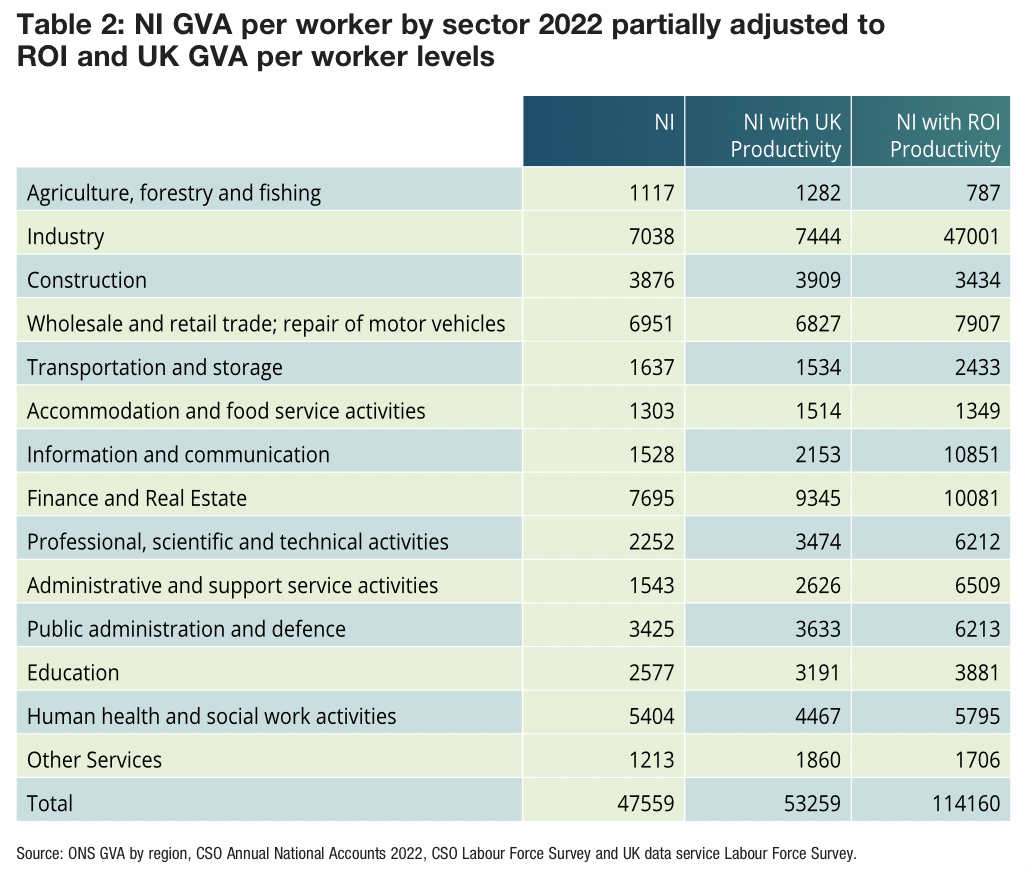

Northern Ireland’s overall productivity performance would increase significantly with UK sectoral productivity levels and would increase dramatically with the Republic’s productivity levels. In first case, UK productivity levels would increase overall productivity level in Northern Ireland by 12 per cent, whereas Republic of Ireland productivity levels would increase it by 140 per cent.

As mentioned previously, the scale of output recorded in the Republic for some sectors is so heavily distorted by the activities of foreign controlled firms that it is not a realistic target for any economy to achieve. Northern Ireland could still seek to meet the Republic’s productivity levels in sectors covering hospitality, transport, and public services, but could not hope to reach productivity levels in other sectors covering manufacturing, ICT, and head office functions which are dominated by foreign firms.

In these sectors where Northern Ireland cannot match the performance of the Republic, it may be more realistic to aim for the performance of that sector at UK level. In this scenario sectors dominated by foreign firms in the Republic and also sectors where Northern Ireland underperforms are adjusted to the UK productivity level. Table 2 shows what this would look like for productivity levels in Northern Ireland, showing a jump of almost 25 per cent in Northern Ireland’s overall productivity performance.

Obviously, switching about productivity levels between regions like this is just a thought exercise. The real job of work will be immense. But we need to start the debate on how we define success in economic policymaking in Northern Ireland.

Yes, the scale of the task may still be considerable, but there needs to be a long-term plan to lift Northern Ireland’s performance. Targets can seed motivation and also allow proper evaluation of success.

If Northern Ireland is to be a successful economy, we need to be more specific and realistic about what the success looks like.