Northern Ireland economy: Overview Protocol boost masks structural problems

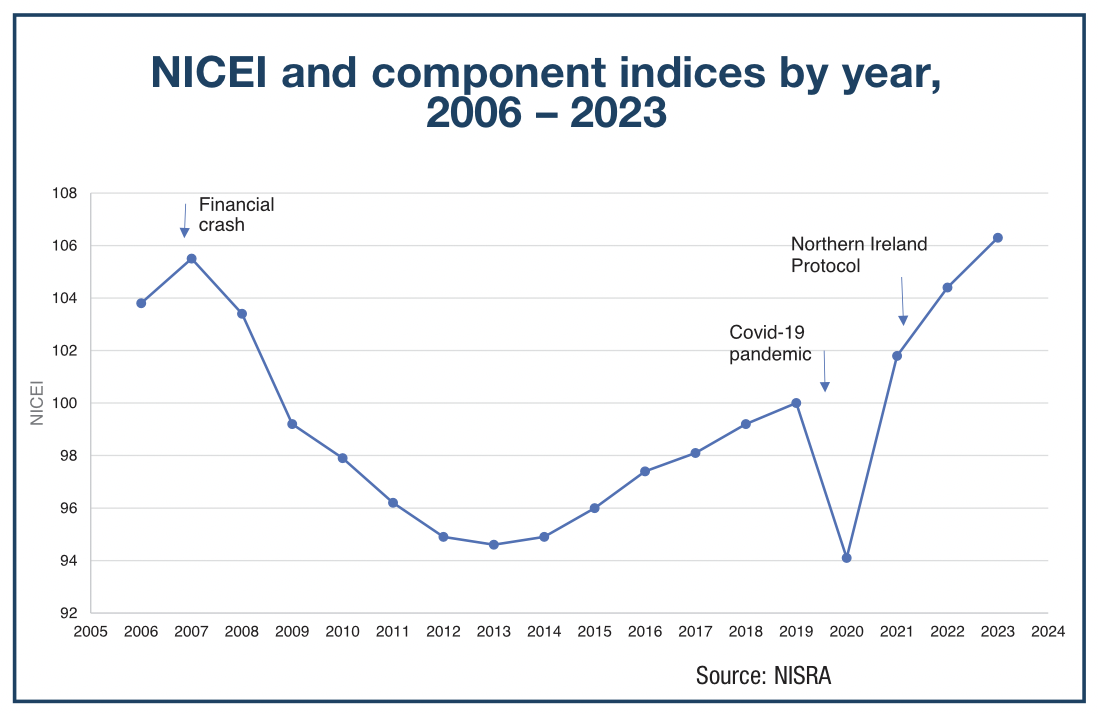

As Northern Ireland’s economy jostles its way out the other side of the Covid-pandemic shock, short-term growth is occurring in the long-term context of a slow return to pre-pandemic economic output, constrained by evident structural problems.

On the face of it, Northern Ireland’s economy is doing well, but the post-Protocol boost is masking long-term structural problems.

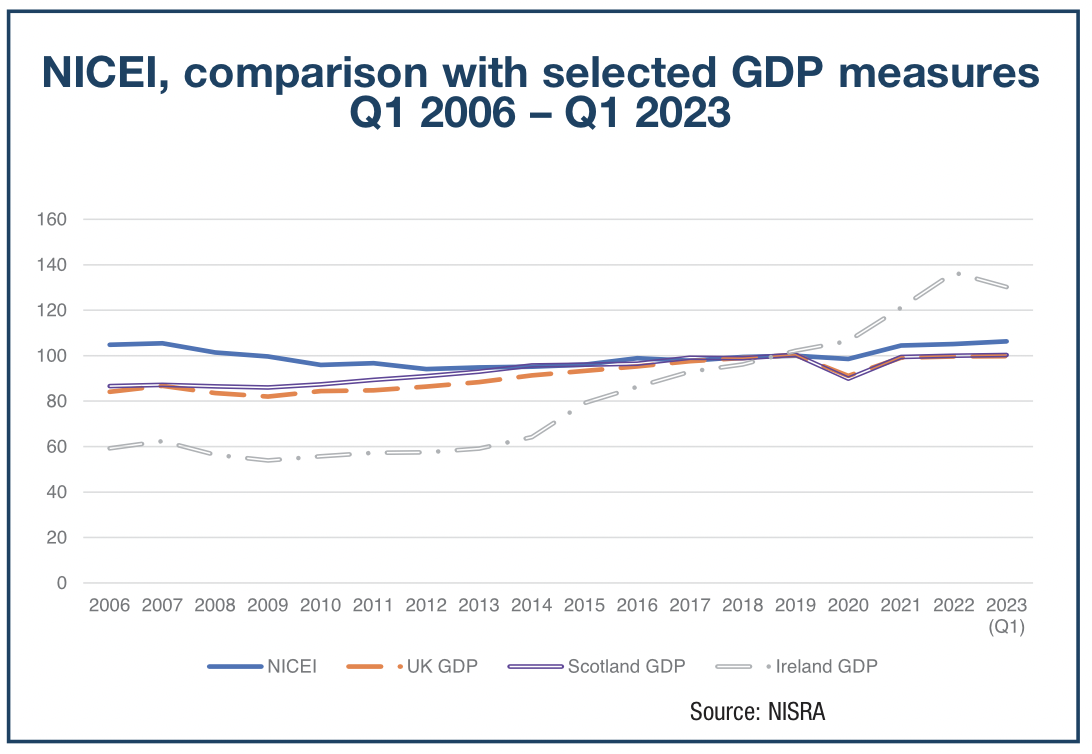

Figures for the beginning of 2023 show an annual growth rate of almost 2 per cent. In the first quarter of 2023, an output increase of 1.7 per cent for Northern Ireland compares favorably to growth of just 0.1 per cent for the UK and a decrease of 4.6 per cent for the Republic of Ireland.

However, such figures fail to accurately depict the extent of the long-term structural problems which have seen little to no significant progress on long-standing plans to transform the region’s economy.

Take for example the Republic of Ireland’s 0.3 per cent decline in GDP over the year compared to Northern Ireland’s 1.7 per cent increase. What these figures fail to depict is that the Republic of Ireland’s GDP is 27.4 per cent above pre-pandemic levels, compared to just 6.3 per cent in Northern Ireland.

Emerging from a technical recession in the second and third quarter of 2022, the NI Composite Economic Index (NICEI) shows that Northern Ireland’s economy has grown significantly faster than the UK economy in the early months of 2023, however, of note is the fact that Q1 2023 is the first time Northern Ireland’s economy has returned to, and risen above, the pre-financial crash high of Q3 2007.

By comparison, UK GDP in the first quarter of 2023 is estimated to be 14.6 per cent higher than its pre-economic downturn peak in quarter one of 2008.

Productivity

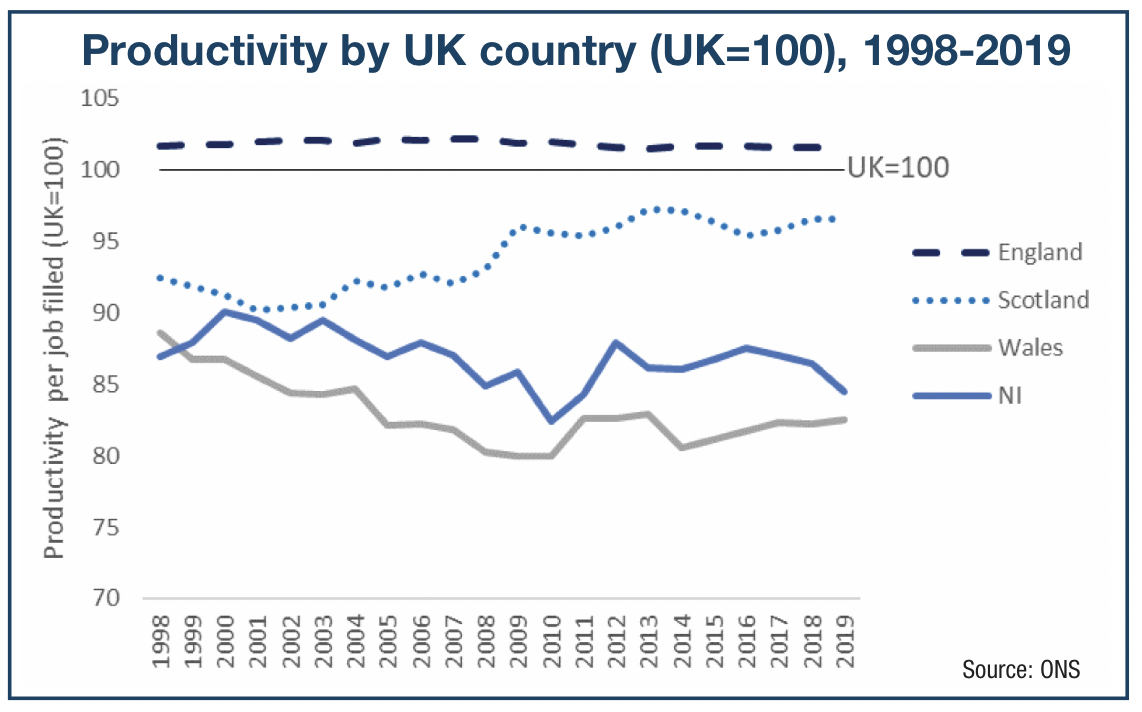

One of the central planks of Northern Ireland’s poor economic performance in recent decades has been around productivity. The Northern Ireland Productivity Dashboard 2022 recently assessed a productivity gap of some 17 per cent between Northern Ireland and the UK average, placing Northern Ireland as the poorest performing UK region for productivity.

Of note is the fact that the UK itself is a productivity laggard when compared to major G7 economies such as France, Germany, and the US.

At the same time, research delivered by the ESRI estimates that since 2000, when productivity on the island of Ireland was largely similar, a productivity gap of almost 40 per cent has emerged – even after the exclusion of economic sectors with high concentrations of multinational companies which are recognised as having a distortionary impact.

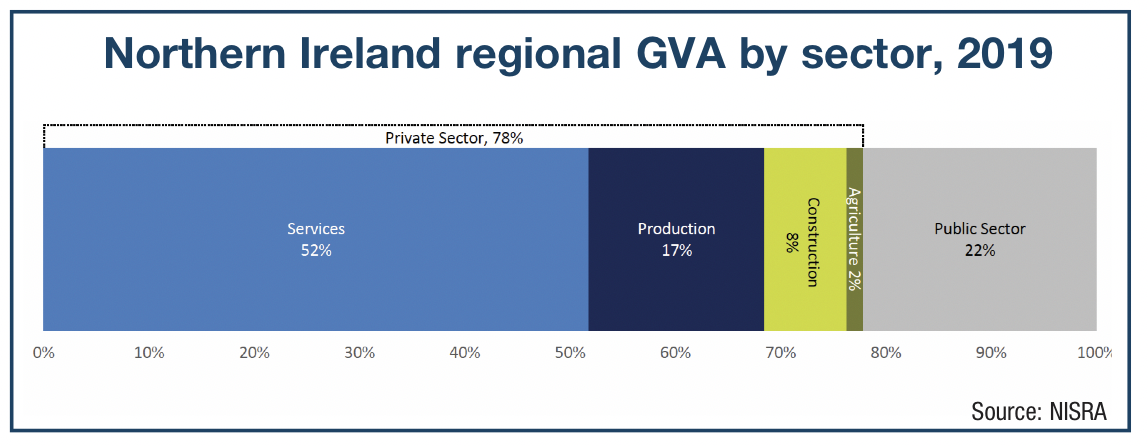

Productivity is a recognised key driver of higher wages and living standards, and Northern Ireland’s long-standing challenge cannot be attributed to one problem alone. Multiple reasons offered include the evolution of the economy away from heavy industry to one with a high concentration of low productivity industries.

For example, one in five (23 per cent) private sector jobs in Northern Ireland are now in the ‘wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles’ industry. The make-up of Northern Ireland’s private sector is also unique in that it is highly concentrated with smaller businesses than many of its neighbouring counterparts. Northern Ireland accounted for just 2.2 per cent of all UK businesses in 2020.

Just over one in 10 private sector businesses generated a turnover of £1 million or more and 90 per cent of private sector businesses have fewer than 10 employees. Northern Ireland also has one of the lowest shares of high-growth businesses at 3.8 per cent of the UK total, or just 285 businesses.

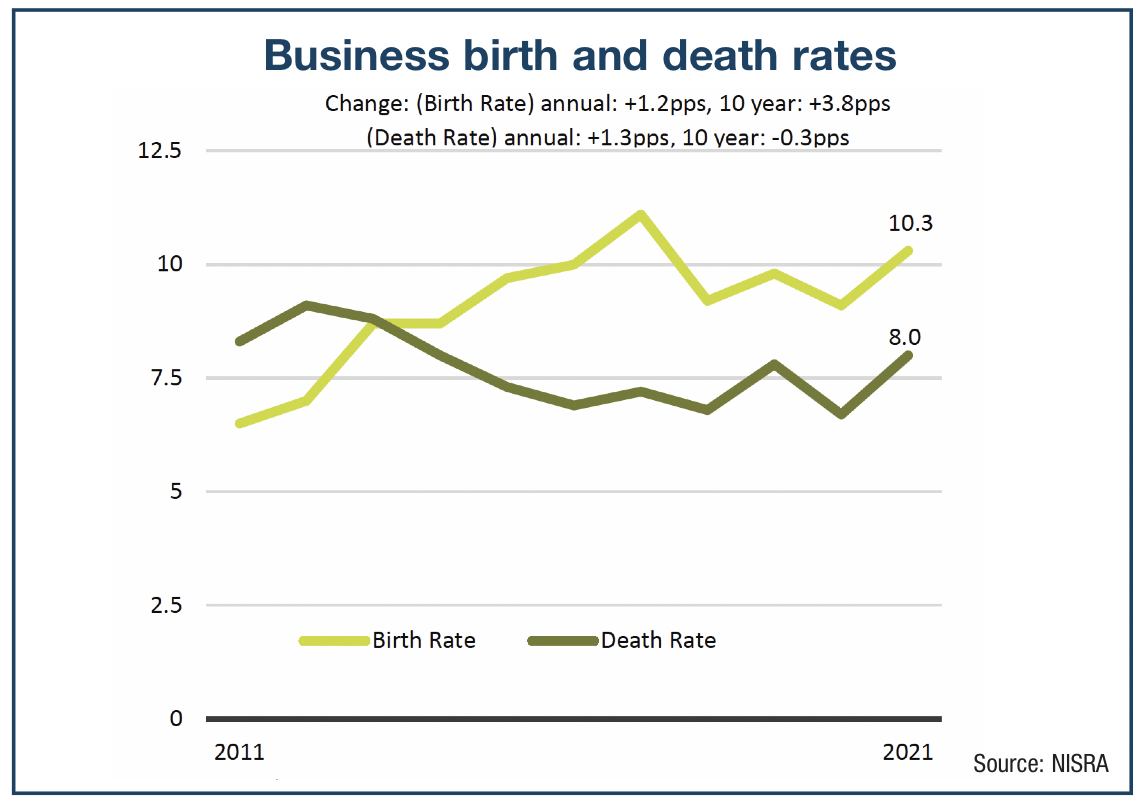

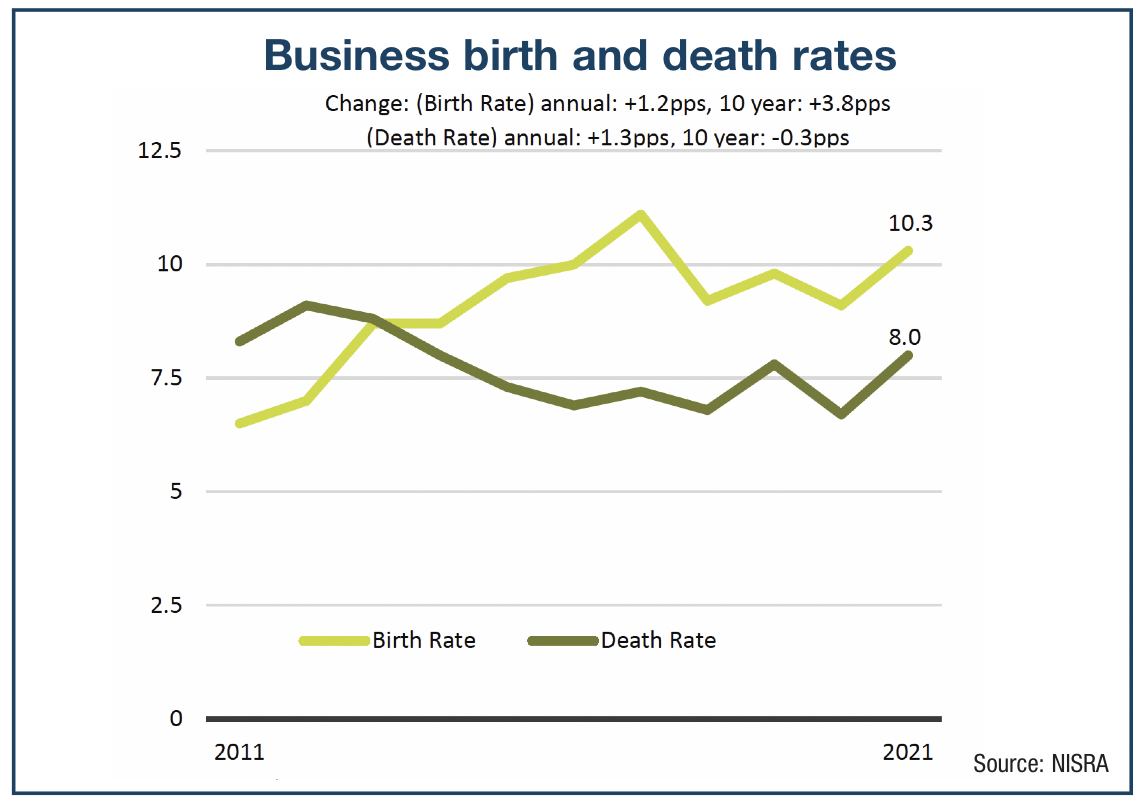

Recent analysis by the Ulster University Economic Policy Centre (UUEPC) points out that Northern Ireland has the lowest business birth and death rates, meaning that the business churn rate (birth rate plus death rate) at 18 per cent (2021) is the lowest in the UK.

“This low business churn rate indicates a less dynamic economy and potentially contributes to Northern Ireland’s lower level of productivity,” it highlights.

Another major pillar of productivity is expenditure in research and development, a key indicator of innovation. Although Northern Ireland’s R&D spending had increased to £880.2 million in real terms in 2021 (up from £718.3 million in 2018), only around two in five businesses in Northern Ireland are classed as ‘innovation active’. Northern Ireland has held the position of having the lowest amount of innovation active businesses across the UK regions for the past decade.

Labour market

Since 2012, Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate has declined significantly and sits at 2.2 per cent. The furlough scheme introduced during the pandemic was highly successful in maintaining the connection between employee and employer, meaning that the number of working age adults in a job (72 per cent) in Q1 of 2023 is close to the pre-pandemic peak of 72.4 per cent.

An important productivity metric to measure is not just the levels of employment, but also the quality of the jobs being performed. Northern Ireland had the third highest proportion of low-paid jobs of all regions in the UK in 2022, despite recording a domestic record low for the proportion of low-paid jobs (13 per cent).

Historically, Northern Ireland has one of the lowest average wages of any UK region. In 2022, median gross weekly earnings for full-time employees in Northern Ireland increased by 2.9 per cent over the year. Northern Ireland’s earnings in 2022 were 11 per cent higher than the pre-pandemic position, meaning it had the highest increase of all UK regions.

However, while the gap between average wages in Northern Ireland and the UK appears to be narrowing, Northern Ireland’s median wage of £575 per week is lower than the UK average of £610. Northern Ireland also has the highest share of employee jobs across all regions of the UK with earnings below the real living wage.

The impact of inflation means that despite increases in median gross weekly earnings, real weekly earnings in Northern Ireland recorded the largest annual decrease on record (4.5 per cent) in 2022.

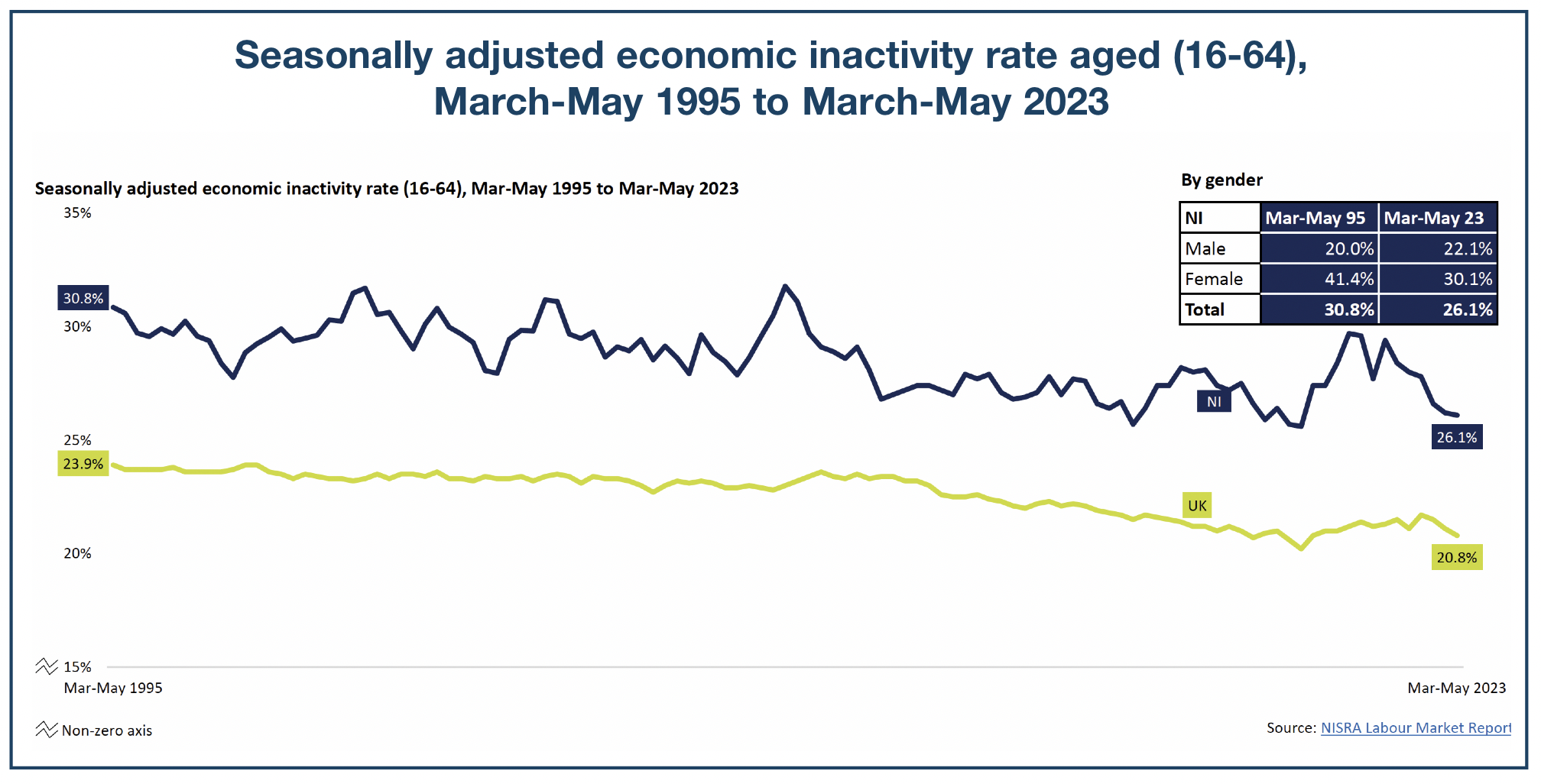

Beyond wages and job quality, Northern Ireland also has a recognised challenge in that it boasts the highest economic inactivity rate of any of the UK regions. The rate is based on those between the ages of 16 to 64 who are not active in the labour market. Northern Ireland’s 26.2 per cent rate is well above the UK average of 21.1 per cent. According to long-term data gathered by NISRA, while high economic inactivity is a long-standing issue, the underlying reason for this high figure has changed with a reduction in the proportion of those inactive due to family and home care reasons, but with long-term sickness now the largest contributor to inactivity.

Education

In parallel with high levels of economic inactivity, Northern Ireland’s economy suffers from a ‘brain drain’ of its highest educated talent. The 2021 UUEPC skills barometer predicted an undersupply of 5,130 jobs annually over the next decade of National Qualifications Framework (NQF) levels 3 and above. This expected skills shortage of the future is underpinned by two main features. Firstly, Northern Ireland’s education disparity, highlighted by the fact that, in 2021, 44 per cent of students were educated to level 4 or above, yet Northern Ireland still has the highest proportion of individuals with low or no qualifications across the UK regions. In 2021, 12 per cent of working age adults in Northern Ireland had no qualifications, double the rate of the UK average. Similarly, Northern Ireland’s lifelong learning rate (18 per cent) has remained persistently lower than the UK average (25 per cent).

In terms of talent retention, 77 per cent of graduates in Northern Ireland in 2020/21 stayed in the region to study compared to 96 per cent for England and 94 per cent for Scotland. The region has the smallest inflow of students from the rest of the UK than any other region and has a low share of foreign students.

Forecast

Recent budget announcements for Northern Ireland indicate a scaling back of spending on public services, which will have a knock-on effect on the private sector, and ultimately limit future expansion of the local economy. Many economists forecast that Northern Ireland will avoid a recession in 2023, with growth estimates ranging from between 0.1 to 0.3 per cent, providing there are no significant economic shocks.

From a broader perspective, recovery of Northern Ireland’s economy has just about returned to pre- financial crisis levels, essentially meaning an extension of what some economists branded the ‘lost decade’. The long-term structural problems that hinder economic growth in Northern Ireland are clearly identifiable, however, policy interventions have failed to make significant impact.

A beacon of hope for the Northern Ireland economy is the opportunity presented by the region’s size and geography within the global push towards decarbonisation. In the recent past, Northern Ireland was hailed as a leader in renewable energy, however, progress has stagnated, again related to the absence of concrete policy and decision-making. An opportunity for economic transformation exists if the region can act as a front-runner of the energy transition, however, current political appetite to seize such an opportunity appears absent.