Oxford Economics regional forecast

In a stark warning, Neil Gibson and Alan Mitchell call on Northern Ireland’s economic policy-makers to plan ahead for further cuts in the block grant and unstable export markets. Radical decisions are needed to avoid future hardship, even if they prove politically unpopular.

Sadly the outlook for the Northern Ireland economy remains broadly unchanged. In crude terms, the forecast can be characterised as ‘challenging in the short term with recovery to come next year, accelerating thereafter’. Worryingly ‘next year’ never seems to come; and the much anticipated recovery seems to be as elusive as ever. This is worrying for traditional economists, obsessed with ‘output gaps’ and ‘spare capacity’.

Their models are not able to explain the unfortunate situation we find ourselves in. External conditions are adding considerably to the headwinds. Uncertainty in the euro zone and a slowing Chinese economy is unwelcome in the face of Northern Ireland’s newly affirmed strategic drive towards ‘export-led growth’. Perhaps economic models are failing us and perhaps recovery is not around the corner. Is it time to devise more radical policy responses?

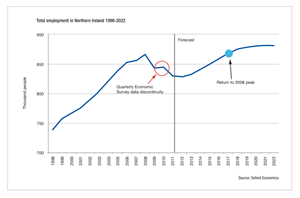

The Oxford Economics autumn 2012 forecast predicts that it will be 2018 before there are as many people in work as there were in 2008, with considerable downside risk attached to this central case. The problems in the Northern Ireland labour market have been dominated by the difficulties in the construction sector (which has lost an estimated 36,000 jobs since 2008). But retail and now public administration are shedding significant numbers of jobs, adding to the gloom.

Professional services and, perhaps rather surprisingly given their dependence on consumer spending, the arts and leisure sectors have been the only private sectors to enjoy expanding employment levels since 2008.

Looking ahead to 2022, professional services and administrative and support services (excluding public administration and defence) are projected to dominate in terms of job creation, with retailing regaining losses and growing in line with the expanding economy. Though manufacturing contributes positively to GDP growth, it is forecast to continue to shed jobs alongside public services which are expected to face even more austerity cuts as UK public finances only slightly improve.

Table 1: Employment by sector 2008-2022

| 2022008-2012 | 2012-2022 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thousand jobs (2008-2012) |

% | Thousand jobs (2012-2022) |

% | |

| Accommodation & food | -0.1 | -0.2 | 6.0 | 13.0 |

| Administrative & support | -4.1 | -8.1 | 12.7 | 27.7 |

| Agriculture | 0.1 |

0.3 | -4.7 | -13.7 |

| Arts & entertainment | 0.8 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 21.1 |

| Construction | -19.6 | -25.2 | 7.4 | 12.8 |

| Education | 0.0 | 0.0 | -2.5 | -3.4 |

| Electricity, gas & steam | 0.2 | 14.3 | -0.2 | -16.2 |

| Financial & insurance | -2.2 | -9.9 | 0.8 | 4.0 |

| Human health & social work | 1.6 | 1.3 | 4.8 | 3.9 |

| Information & communication | -0.7 | -3.5 | 3.1 | 16.5 |

| Manufacturing | -7.5 | -8.4 | -3.5 | -4.2 |

| Mining & quarrying | -0.5 | -25.9 | -0.4 | -22.4 |

| Professional activities | 2.5 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 24.5 |

| Public administration & defence | -3.4 | -5.4 | -4.0 | -6.8 |

| Real estate | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.9 | 23.1 |

| Transportation & storage | -0.6 | -1.9 | 4.4 | 14.5 |

| Water supply | -0.2 | -4.4 | -0.5 | -9.2 |

| Wholesale & retail | -6.4 | -4.2 | 11.6 | 8.0 |

| Other services | 2.2 | 11.7 | 3.4 | 16.2 |

| Total | -37.8 | -4.4 | 53.2 | 6.4 |

Source: Oxford Economics

Note: There is a data discontinuity in the DETI Quarterly Employment Survey data in September 2009. All estimates over this period should be used with caution.

Table 2: Total employment change by district council 2012-2022

| Council | Thousand jobs | Return to peak |

| Antrim |

2.0

|

2015

|

| Ards |

1.3

|

>2022

|

| Armagh |

1.4

|

2016

|

| Ballymena |

2.6

|

2017

|

| Ballymoney |

0.4

|

>2022

|

| Banbridge |

0.7

|

>2022

|

| Belfast |

15.9

|

2017

|

| Carrickfergus |

1.1

|

2013

|

| Castlereagh |

1.9

|

2016

|

| Coleraine |

0.4

|

>2022

|

| Cookstown |

0.47

|

2016

|

| Craigavon |

3.5

|

2014

|

| Derry |

2.9

|

2013

|

| Down |

0.7

|

>2022

|

| Dungannon |

1.3

|

>2022

|

| Fermanagh |

1.5

|

>2022

|

| Larne |

0.4

|

2017

|

| Limavady |

0.2

|

>2022

|

| Lisburn |

3.9

|

2015

|

| Magherafelt |

1.0

|

>2022

|

| Moyle |

0.2

|

>2022

|

| Newry and Mourne |

3.4

|

2017

|

| Newtonabbey |

2.2

|

2018

|

| North Down |

2.1

|

2013

|

| Omagh |

1.1

|

>2022

|

| Strabane |

0.4

|

>2022

|

Source: Oxford Economics

Table 3: Summary of forecasts (2012-2015)

|

Key indicators

|

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population (thousands) |

1,825

|

1,839

|

1,852

|

1,863

|

| GVA (£ billion) |

27.096

|

27.504

|

28.284

|

29.112

|

| Total employment (thousand jobs) |

828

|

832

|

840

|

850

|

| Unemployment (thousands) |

63

|

64

|

63

|

61

|

| Northern Ireland % growth |

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

| Population |

0.7

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

0.6

|

| GVA |

0.0

|

1.5

|

2.8

|

2.9

|

| Total employment

|

-0.2

|

0.5

|

1.0

|

1.1

|

| Unemployment |

5.6

|

1.0

|

-1.8

|

-2.5

|

| UK % growth |

2012

|

2013

|

2014

|

2015

|

| Population |

0.8

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

0.6

|

| GVA |

0.3

|

2.0

|

3.3

|

3.3

|

| Total employment |

0.3

|

0.8

|

1.4

|

1.5

|

| Unemployment

|

5.8

|

-0.7

|

-5.3

|

-5.9

|

Source: Oxford Economics

…leaving certain areas in real long-term trouble

At a local level, the Oxford Economics forecasts are alarming, particularly for areas outside the core urban centres. With an outlook heavily dominated by service sector jobs, the growth is clustered around city areas where graduate labour supply is most readily available. Construction and retailing have been such a significant part of the job creation story in many parts of Northern Ireland that their continuing difficulties will have a very pronounced effect.

A resurgence in manufacturing and the agri sector (both of which have enjoyed noteworthy success in recent times) would be extremely beneficial for many of the areas which face a decidedly uncertain labour market future if the Oxford Economics forecasts prove accurate. At present, the economic visions set out in both the Programme for Government and the DETI Economic Strategy have limited quantification around their job targets, either sectorally or spatially.

The only directly quantified targets that are at an aggregate level are: moving 114,000 working age benefit clients into employment by March 2015, promoting 6,300 jobs in locally owned companies and a further 6,500 new jobs in new start-up businesses, and promoting 5,900 jobs from inward investors. The Oxford Economics model highlights the potential divergence in economic fortunes across the island of Ireland unless the outlook for Northern Ireland is substantively different to the currently projected base case.

Is hope for recovery misguided?

It can be difficult to write commentary on the Northern Ireland economy at present. There is little merit in constantly painting a gloomy picture and re-hashing old messages but equally, if the focus is to shift to talk of recovery, it is important to ask: “How valid is that recovery? What will drive it?”

Crudely speaking, economic fortunes are dictated by what happens to consumer spending, government spending, investment and trade. Given the challenging labour market outlooks, the limited ability for pay rises (either in the public or private sector), as well as other downward pressures on incomes, there is little reason to be confident that consumer spending can, as it has done so frequently in the past, be the driver of recovery.

A slight cooling of prices as global demand cools is welcome, and evident in the inflation numbers. But many people in Northern Ireland are heading into a third or fourth year of falling real incomes. The Government is also operating in a very constrained environment with the UK public finances showing no sustained sign of improvement and thus this is unlikely to provide much of a stimulus. That leaves business investment and trade as candidates to lead the recovery. Whilst it is true that major corporates are cash-rich, there are relatively few unique opportunities in Northern Ireland and the same message does not hold for smaller firms.

More importantly, given the problems elsewhere in the economy, the reluctance of businesses to invest is evident. They want to know: “Where are the customers?” The opportunities for trade are clear, but the competition is fierce. Northern Ireland has limited direct access to many of the markets and its citizens have a limited language skills set. These factors, alongside weakening world trade resulting from escalating difficulties in the euro zone and moderating rates of growth in economies such as China, mean that trade may not be the immediate saviour required, certainly in terms of job creation.

Sadly this paints a picture of an economy which has no customers, or in economic parlance, little demand. Does this suggest austerity policies are misguided? Perhaps, but injecting money into the economy, or reducing the scale of cuts, comes with one large proviso: who will lend the money to invest at affordable rates?

The experience of Greece, Ireland, Portugal and more recently Spain and Italy indicate that once the market loses confidence, it is hard to attract the finance required. A credible case of a ‘boosting demand’ strategy leading to growth and rebalanced budgets may well be necessary to convince the markets that current policies are misguided.

Do we really understand the reality of the situation?

Watching economic policy debates in Northern Ireland can be a frustrating experience. Almost all policy solutions are heavily criticised and rejected but very little is offered by way of suggested alternatives. This is unhelpful as it does not allow a very mature policy debate to develop.

There are no official fiscal ‘accounts’ for Northern Ireland as a UK region so any figure of its effective deficit (how much it generates in tax less what it spends on public expenditure) is only an estimate. Oxford Economics put the current deficit estimate in the region of £11-12 billion. This deficit is roughly equivalent to funding the Olympics every single year in Northern Ireland.

There are very valid reasons why the region should be supported by more affluent parts of the country; it is one of the advantages of a fiscal union. But the GB tax-payer is quite rightly beginning to ask the question: is this the best use of £11-12 billion of our taxes? To put the figure in context, Northern Ireland’s health sector spending costs approximately £3.5 billion and the total social protection bill (including welfare payments and pensions) comes to £8 billion according to HM Treasury Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (PESA) data.

This suggests, left to fund our own services with our estimated revenue of around £12 billion, we could afford our social protection and health bills but nothing else e.g. the cost of running the Civil Service, police, education, economic development. The subvention is roughly equivalent to 30-40 per cent of GDP, more than any other European country’s deficit at any point during the crisis to date.

These numbers need to be clear when framing discussions on service provision or proposed policy changes. Northern Ireland needs to find a find way to reduce this level of dependence in the longer run or hope that its ability to protect the block grant continues. Admittedly, it has been extraordinarily successful at doing this up to now but then the UK finances have never been in such a perilous state.

Is it time for a more radical policy direction?

Reiterating the scale of the problem is helpful to a point, but suggesting solutions is more difficult and more often than not deeply unpopular. There are no easy answers, but it is incumbent on any author when predicting a less than favourable outlook to at least attempt to suggest areas of possible policy change:

- Decide on corporation tax: Many people, the authors of this article included, are convinced that a reduced rate of corporation tax would bring substantial economic benefits to Northern Ireland and reduce its dependence on the block grant. Sadly, the ‘price’ that would have to be paid for this policy lever remains an area of heated debate. It is disappointing that legislation was not changed four years ago when initial modelling estimates of the benefits emerged to make companies report regional profits. By now, an effective evidence base would exist for calculating the cost. As it is, no final figure is agreed and the policy remains in limbo. A conclusion to the debate would be welcome.

- Review of revenue-raising options: Many sources of potential revenue exist. It could be reform of the rates base, considering whether existing caps on domestic properties and sectoral dispensations remain appropriate. It could be water charging or more aggressive tax penalties for less desirable aspects of society e.g. criminality, public eyesores or derelict buildings. Perhaps more aggressive environmental taxation to encourage green investment. Asking how Northern Ireland could raise an extra £1 billion in taxes to fund other activities would be a useful exercise to at least understand the possibilities. Of course, no-one likes tax rises but the exercise in seeing what it would take to raise a #1 billion would help people understand the subvention and prepare Northern Ireland for possible future cuts.

- Incentivise expenditure saving: At present, any reduction in benefit levels does not feed back into the Executive’s hands but rather to Westminster and thus the fiscal motivation to tackle long-standing issues of dependency is diminished. Exploring the possibility of a form of earn-back scheme to let Northern Ireland keep some of the savings could be very beneficial, were the savings to be effectively re-invested.

- Prioritising infrastructure investment: Capital expenditure is always cut first in any time of austerity. With an ailing construction sector and a demonstrable deficit in certain infrastructure areas, it makes sense to consider bringing forward planned investment. Determining what to prioritise is challenging but accelerated investment would bring an immediate boost. Would civil servants be happy with a 1 per cent pay levy to pay for an infrastructure investment programme? Unlikely, but it would help move activity towards the private sector: a stated policy aim which is not best served by infrastructure cuts and the much lauded reduction in consulting spend (author’s vested interest duly declared).

There are, of course, many more areas for radical policy shifts, but what simply must happen is that we think beyond our borders, realise the world is changing and accept that no-one owes us a living. The process of planning for a world in which the GB tax-payer is less benevolent is surely prudent if nothing else. It will perhaps throw up some unlikely new solutions to a long-standing problem that Westminster has previously allowed Northern Ireland to ignore.

160,000 jobs at £50,000 salary needed

As a rough guide, if the Northern Ireland economy created 160,000 jobs at £50,000 per annum salary in businesses with a 50 per cent profit margin, the economy would reach parity with Great Britain in overall standards of living (GVA per capita) by 2020 (or 65,000 jobs to reach parity if the greater South East is excluded). This is the scale of challenge ahead.

To get anywhere near that kind of step change, all policy options need to be considered. A proper economic debate needs to take place when policy changes are mooted. We need to move from objection to options, from denial to debate. Only then would the first steps be taken towards a forecast that would no longer look (sadly) like so many that have gone before it.

Neil Gibson is Director of International Cities and Regions and Alan Mitchell is an economist for Great Britain and Northern Ireland services, both at Oxford Economics.

www.oxfordeconomics.com