New decade, same approach

An Executive split on many issues, delays in delivery of crucial reforms and a bleak economic outlook: one year on from the New Decade, New Approach (NDNA) agreement it appears little has been done to bring forward the new way of progressive governance promised in the deal, writes David Whelan.

New Decade, New Approach was largely welcomed, with most people recognising that over three years of ‘direct rule-light’ by Westminster had only served to compound the lengthy list of historical challenges which have dogged Northern Ireland.

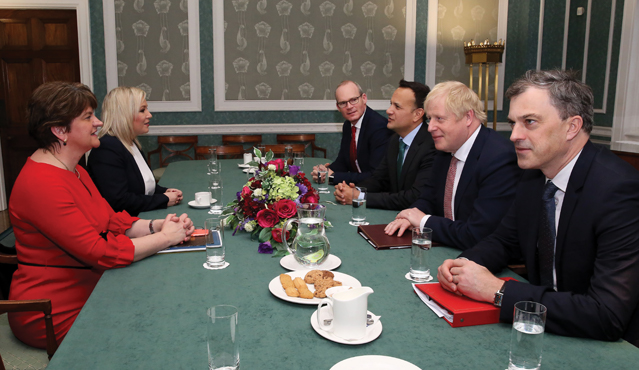

A period of “decay and stagnation” as described by the then Head of the Civil Service David Sterling was set to be addressed by the return of local decision-makers. New Decade, New Approach was billed as not only brokering the return of Northern Ireland’s main political parties to the Executive table but also as a platform to transform public services and to restore public confidence in devolved government.

Over one year on, the deal has delivered little evident progress on many of its pledges and the strained Executive relationships bear a striking resemblance to those witnessed in previous mandates.

The emergence of Covid-19 can, quite rightly, be pointed to as cause for delay in many areas but the problems are more deep-rooted than the diversion of resources, as evidenced by the fact that the restored Executive has yet to deliver a timeline for the delivery of a Programme for Government.

A number of other pre-Covid factors can be identified for why the agreement has, to date, failed to live up to expectations. The first being that while all parties in the Executive signed up to the ambitions of New Decade, New Approach, the deal was sculpted by the British and Irish Governments. While both governments will argue that the deal was informed by nine-months of talks, the timing was such that the parties faced an ultimatum to agree or face a fresh round of Northern Ireland Assembly elections. There is an evident absence of ownership of much of the agreement’s promises by local ministers.

The second reason, highlighted at the time, was the absence of a concrete funding package aligning with the various commitments. New Decade, New Approach set out an ambitious agenda for investment but project-specific investment was lacking. The Department of Finance stressed that the £2 billion described by the British Government, comprised of very little ‘new money’ and instead was largely made up of Barnett consequential and the pre-existing confidence and supply agreement. Covid support measures have muddied the waters further in this regard, with resources from the UK Treasury largely being redirected to mitigate immediate health and economic pressures.

A third fundamental reason is the context in which the two largest and ideologically split parties were placed back into power sharing. Brexit was a looming shadow over the agreement in January 2020 and it was predictable that an agreed economic outlook would not be achievable while the UK’s direction of travel remained uncertain. Constitutional allegiances also appear to be dominating the Executive’s Covid-19 response and as such, Executive relationships have tilted towards breaking point on several occasions. Ironically, the pandemic appears to be the binding reason that the Executive has not collapsed.

“There is an evident absence of ownership of much of the agreement’s promises by local ministers.”

However, some progress has been made under New Decade, New Approach. In fact, the resumption of the Executive had an almost immediate impact as the Health Minister Robin Swann MLA had to settle pay disputes with nurses and teachers. Other progress of note includes the launch of a discussion document on a Climate Change Act and a Clean Air Strategy, a new ministerial code and new rules around special advisors (although a Private Members’ Bill tabled by the TUV’s Jim Allister is seeking to overrule these and legislate for rules around SPADs) and planning permission being granted for the North South Interconnector.

It should also be noted that a great deal of work has gone into the reconfiguration of services to adjust to Covid-19 including in health, education and through the Department for the Economy’s roll out of various support schemes.

However, many deadlines outlined in the original document have been missed and notably, little commitments have been given to renewed timeframes. No timeframe has been set for a new Programme for Government over a year on from the Executive’s resumption and with just slightly over a year left of the current mandate. Similarly, a new action plan on hospital waiting times promised in January 2020 is still absent, with figures actually worsening to the point where almost half of those in Northern Ireland waiting for a consultant-led outpatient appointment have been doing so for more than a year. A Mental Health Strategy was also promised by December 2020 but has yet to emerge.

Financing NDNA’s aspirations has also proven problematic. Multi-year budgets to tackle long-standing challenges have yet to be achieved with the Finance Minister Conor Murphy MLA bemoaning his latest draft Budget as a “standstill” of the previous year and blaming the Treasury for its one-year nature. The latest budget included administrative costs for victims’ pensions payments but no concrete funding with both governments engaged in a stand off over who will pay the bill, not the outcome envisioned by those who read the NDNA promise of “the Executive will press on with implementation of a redress scheme for victims and survivors of historical abuse, making payments as early as possible”.

Many other issues remain outstanding, some appear yet to have been initiated. The delivery of sustainable core budgets for every school will be a challenging ask before March 2022 and little progress appears to have been made on appointments of Irish language and Ulster Scots commissioners, despite being a key stumbling block in restoration negotiations pre-January 2020.

When assessing the progress under the NDNA agreement it is worth reflecting on the deal’s ambitions. “The Executive will bring positive changes in areas that impact greatly on people’s lives such as the economy, overcrowded hospitals, struggling schools, housing stress, welfare concerns and mental health,” the deal outlined. None of the above have been achieved to a level which most would have hoped for when presented with the ambitions.

Furthermore, hopes of the emergence of a new way of working in the Executive have been undermined by clear splits over Brexit, Covid-19 restrictions and the approach to marking 100 years of partition.

The failure of the First and deputy First Minister to agree on a new Head of the Civil Service at a time of crisis has been held up as evidence of failure to adopt the new ‘culture’ of power-sharing teased by NDNA.

The pandemic and the long-term fall out of its economic and societal impacts are set to intensify the challenges the Executive faces on delivering on the agreement’s priorities. With less than 15 months left until the next Assembly election, the Executive would need to radically alter its mechanisms of delivery to achieve this. It is underwhelming and potentially telling that over a year on, we do not even have a Programme for Government from which we can assess which elements of the agreement the Executive view as priorities.