Mother and baby homes public inquiry ‘not off the table’

The Northern Ireland Executive has fallen short of calling a full public inquiry into historic institutions in Northern Ireland, including mother and baby homes.

The Executive has not ruled out holding a public inquiry in the future but has for now opted for an independent investigation, which it says will be “co-designed and victims centred”.

Some victims and survivors have expressed their disappointment in the failure to call a full public inquiry, with powers to deliver truth and justice, and raised concerns about the length of time an investigation will take.

Amnesty International first submitted a paper to the Northern Ireland Executive making a case for a public inquiry into abuses in homes in 2013.

The decision comes after the conclusion of a Commission of Investigation in the Republic, established in 2015, into Ireland’s mother and baby homes. Amidst some of the shocking findings was an “appalling level of infant mortality”. However, following such a long wait, many survivors were left disappointed and rejected some of the findings, not least that no evidence was found that women were forced into the homes by Church or state authorities and “very little evidence” of forced adoptions.

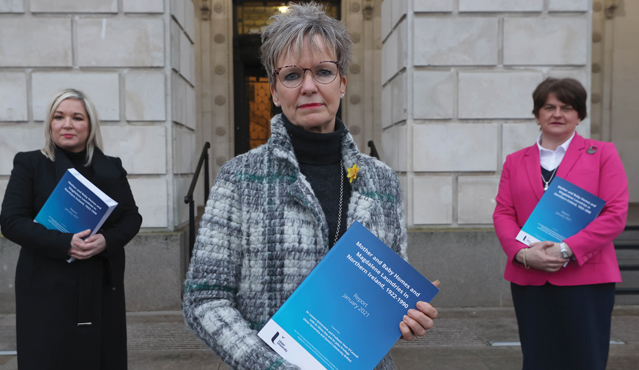

The decision in Northern Ireland was taken after the publication of research undertaken by Queen’s University Belfast and the University of Ulster in January 2021 into eight mother and baby homes, a number of former workhouses and four Magdalene laundries run by the Catholic and Protestant churches between 1922 and 1990.

The research was commissioned by the Department of Health in 2018 and was initially expected to take 12 months.

In July 2020, the Department of Health and the Executive Office announced the appointment of Judith Gillespie, the PSNI’s former Deputy Chief Constable, as the Independent Chair on an inter-Departmental working group. Gillespie, who will lead on the investigation, has said that a public inquiry is “not off the table” but insisted the importance that survivors have agency in the process.

The academic research found that over 10,500 women went through mother and baby homes in Northern Ireland and 3,000 were admitted into Magdalene laundries. The research’s figures were conservative when considering that some records were incomplete.

Mother and baby homes were used to house women and girls who became pregnant outside of marriage and in Northern Ireland the number of women in these institutions peaked in the late 1960s and early 1970s but continued to be active up until 1990.

Included in the women housed in mother and baby homes in Northern Ireland were girls as young as 12. The oldest person admitted to a home in Northern Ireland was 44 but most were aged between 20-29. Close to a third of women were under the age of 19.

While the majority of women who entered the homes were from Northern Ireland (86 per cent), some were also from the Republic of Ireland (11.5 per cent) and Great Britain (2 per cent). Records show that home addresses were listed for some of the women from as far away as the USA, South Africa and the Netherlands.

Some of the women placed in homes were victims of sexual crime, including rape and incest. However, most were admitted because of the stigma attached to pregnancy outside of marriage and were placed there by families, doctors, priests, and state agencies.

The report found that women were required to carry out tough chores late into their pregnancy and were given little preparation for childbirth. In the majority of testimony gathered for the research, most identified trauma and, often, mental health issues as outcomes of birth mothers’ experiences around their pregnancy. This finding was more acute in cases where adoption was the outcome.

Most of the homes did not have their own maternity ward and so many women gave birth in local hospitals or private nursing homes. Not all mothers returned with their child to the mother and baby home following birth and it is noted that of those that did, unlike the Republic of Ireland, most did not remain for a very long time after they had given birth. For this reason, Northern Ireland’s mortality rates for mother and baby homes are much lower than compared to homes in the Republic of Ireland. Data suggests a 4 per cent rate of babies stillborn or who died shortly after birth across the entire period.

However, the report notes the need for a more detailed overview of the mortality rates for babies born in mother and baby homes through scrutiny of records for those baby homes to which an estimated 32 per cent of infants were sent following separation from their birth mothers, which were not on the list of institutions under assessment. Records for only one such home were assessed, and information suggests that at one point during the 1920s, death rates may have been as high as 50 per cent for those admitted.

Of the mother and baby homes assessed for the research, only two recorded detailed information of where birth mothers went after they left the institution. Only 26 per cent of babies left the homes with their mother, some of which may have been placed for adoption or into care. The available records on immediate destination indicate 32 per cent of babies were placed in institutional homes. A further 23 per cent were recorded as adopted, with another 15 per cent listed as going to foster parents.

“In the majority of testimony gathered for the research, most identified trauma and, often, mental health issues as outcomes of birth mothers’ experiences around their pregnancy. This finding was more acute in cases where adoption was the outcome.”

The report investigated the matter of consent of women in the homes and found that given the options available to birth mothers, signing adoption papers “was not a heartfelt indicator of their consent” and outlined evidence that “there have been long-term mental health implications in the wake of these life-changing decisions”.

Additionally, the report provides evidence of cross-border movement of women and children into and out of the institutions, with some babies moving to homes in the Republic of Ireland where they were then adopted in the State or in the USA or Britain and calls for further investigation into adoption from mother and baby homes.

Speaking in the Assembly in late January, First Minister Arlene Foster said that voices of survivors of mother and baby homes in Northern Ireland will be heard “loudly and clearly” through the independent investigation.

Foster set out a six-month timeframe for the work, which she said would begin immediately and outlined that a statutory public inquiry “may well be the outcome of that process” but that it was important that victims and survivors were given the opportunity to influence that.

Following publication of the research, Archbishop Eamon Martin, the leader of the Irish Catholic Church, expressed his embarrassment and guilt over the church’s contribution and bolstering of a “culture of concealment, condemnation and self-righteousness”.

“For that I am truly sorry and ask the forgiveness of survivors,” he said.

Acknowledging that the establishment of an investigation in six months may appear an unnecessary delay, Chair of the Executive’s independent inter-departmental working group, Judith Gillespie, added that it was “better to get it right than rush and get it wrong”.