Mental health delays

The long-awaited publication of a mental health strategy for Northern Ireland is set to be further delayed due to the pandemic workload, despite recent findings that a third of people in Northern Ireland met criteria for depression and anxiety related to Covid-19.

The Department of Health has included a dedicated Covid-19 Mental Health Response Action Plan in its Mental Health Action Plan published in May but states that co-production of the anticipated 10-year mental health strategy has not been “possible as expected”, meaning the strategy will not be published by the end of this year as anticipated.

Recent research produced by Queen’s University Belfast, which explored the psychological impact of lockdown and the pandemic on people in Northern Ireland, found that of those surveyed 30 per cent met the criteria for anxiety, 33 per cent for depression and 20 per cent met the criteria for Covid-19 related PTSD due to the current pandemic.

At the same time it’s been revealed that additional monies of £1.35 million secured for Northern Ireland’s latest suicide prevention strategy published in September, have yet to be allocated.

Northern Ireland remains the only region of the UK without a dedicated mental health strategy, despite recording the highest mental illness levels of any region. Recent statistics prior to the Covid-19 outbreak, show that rates of mental health illness are 25 per cent greater in Northern Ireland than in England.

The New Decade, New Approach document, which saw the resumption of devolved government in Northern Ireland, set out a target to have a mental health strategy published before the end of 2020. In the meantime, however, the Bamford Review continues to inform policy on mental health in Northern Ireland, despite having begun in 2002 and completed in 2008. Calls for a dedicated strategy on mental health have been long-standing given the stark reality of statistics in Northern Ireland.

Around 6 per cent of Northern Ireland’s health budget is dedicated to mental health, half of what England dedicates to the challenge. Professor of Social Policy at Ulster University, Deirdre Heenan, recently stated that the relatively low level of investment has “led to underfunded psychological and mental health services and increasing waiting times”. Adding that: “This legacy of increased psychopathology and under-resourced services is reflected in general practitioner prescribing rates for antidepressant medication, which are the highest in the UK.”

The Minister for Health Robin Swann outlined suicide prevention, mental well-being and mental health services as his top priorities upon taking up the post. While many will welcome that steps have been taken to outline an action plan in the lead up to a long-term strategy, there is also a recognisable desire to see adequate levels of funding associated with planned measures.

There is hope that a long-term strategy will go further than recent measures taken by the Department in relation to mental health, such as the Protect Life 2 strategy. The strategy was published in the absence of a minister, a fairly unprecedented step, in September 2019 and was welcomed in its ambition to reduce the suicide rate in Northern Ireland.

Criticisms of the strategy centred on the absence of guaranteed long-term funding but it was also argued that the decade-long strategy was under ambitious in its targets for addressing the suicide crisis, while an implementation plan has yet to be produced.

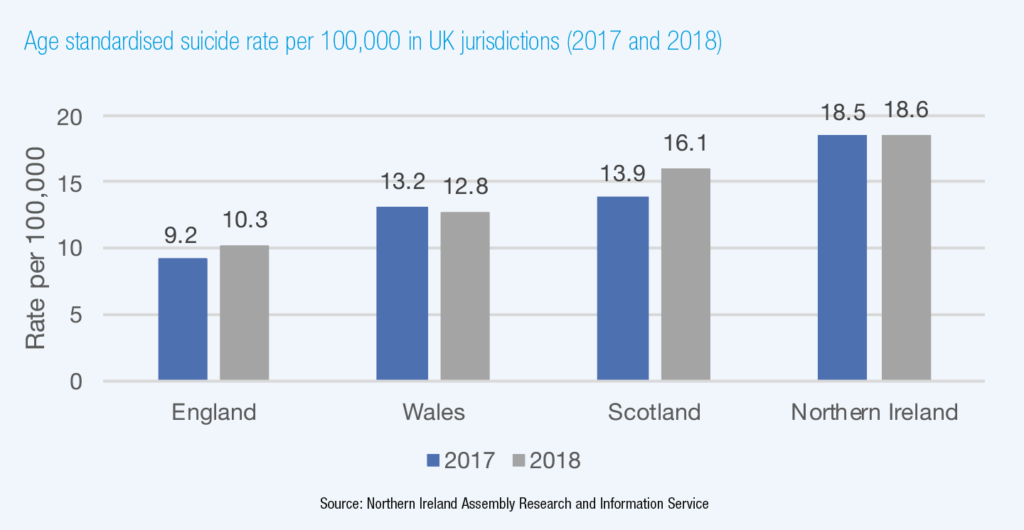

The target of a 10 per cent reduction in the suicide rate in Northern Ireland within five years would mean that the recent figure of 16.5 deaths by suicide per 100,000 of the population in Northern Ireland would be reduced to 14.9 deaths. In comparison, the overall rate in the rest of the UK is around 10.1 deaths per 100,000.

The strategy was ambiguous around future funding. The Department of Health, through the Public Health Agency, invests around £8.7 million annually in suicide prevention, an estimated 0.16 per cent of the overall annual health budget and it was outlined at the publication of the strategy that a further £1.35 million had been secured for the 2019/20 financial year, through additional health transformation funding allocated under the confidence and supply package.

However, a spokesperson for the Department of Health has confirmed that the £1.35 million is “part of the decisions that have yet to been taken on funding of further suicide prevention projects in this financial year”.

Asked whether, following the return of ministerial decision making, the strategy has been progressed the official confirmed that both an Executive Working Group on Mental Wellbeing, Resilience and Suicide Prevention and the Protect Life 2 Steering Group had been established and had met and added that “the Department intends to upload a summary of current implementation of Strategy actions to the Departmental website shortly”.

On whether further funding considerations had been given to the strategy, he added: “In addition to the existing £8.7 million budget for suicide prevention, £300,000 additional funding has been allocated to extend the Self Harm Intervention Programme in 2020/21. Decisions have not yet been taken on funding of further suicide prevention projects in this financial year.”

The Department’s mental health action plan has been recognised as progress, however, it is likely most will reserve judgement until delivery of the strategy has commenced. Core themes of the strategy are centred on three categories: immediate service development, aiming to fix immediate problems; longer term strategic objectives, such as an overall workforce review; and preparatory work for future strategic decisions, such as further action plans on technology integration or governance changes.

A number of planned reviews have also been outlined including a review to consider the response to homicide and suicide, the use of restraint and seclusion, transitions between CAMHS and adult service and old age psychiatry, outcomes data collection and future inclusion of community and voluntary sector’s role in core mental health services.

However, detail is scarce on funding commitments under the action plan and it does not provide resource details for actions that will require additional funding. The plan does provide some specific costs associated with year one, an estimated cost of £2.8 million in total, however there is broad acknowledgement that some of these associated costs will rise substantially, annually.

“I welcome the publication of the plan as it focuses attention on the long-neglected issue of mental health. However, this is just a plan, setting out a list of actions. Delivering long-lasting positive change for mental health requires leadership, vision funding and investment,” said Professor Heenan.

“A 10-year strategic plan with appropriate financial underpinning is required to address the systemic issues around mental health including education, evidence-based interventions, workforce planning and governance.

“Despite the relatively high rates of mental illness Northern Ireland remains the only region of the UK without a strategic plan to ensure good mental health. Time is of the essence urgent, bold, decisive action is needed to ensure that we do not let down another generation.”