Major labour market shifts

Efforts to bring Northern Ireland’s unemployment rate to a record low are set to be drastically undermined by the economic fallout of Covid-19 as early indications show a doubling of unemployment and spike in proposed redundancies.

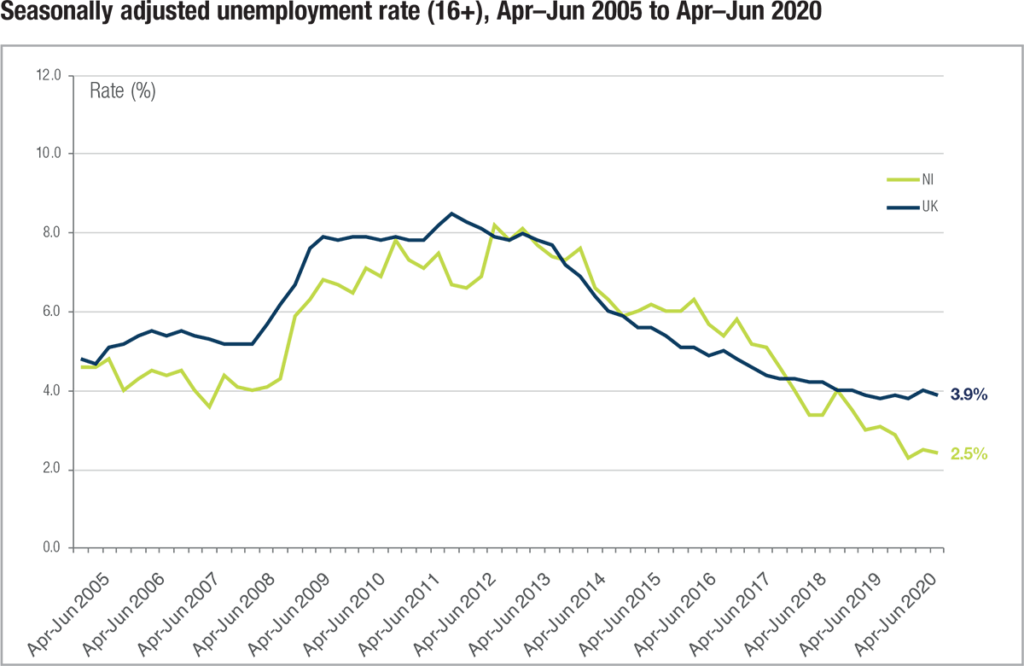

In April, the announcement of Northern Ireland’s unemployment figure of 2.5 per cent, a record low for the region, was cautiously welcomed as economists and businesses recognised that the figures failed to reflect the extent of the economic damage being done by the pandemic.

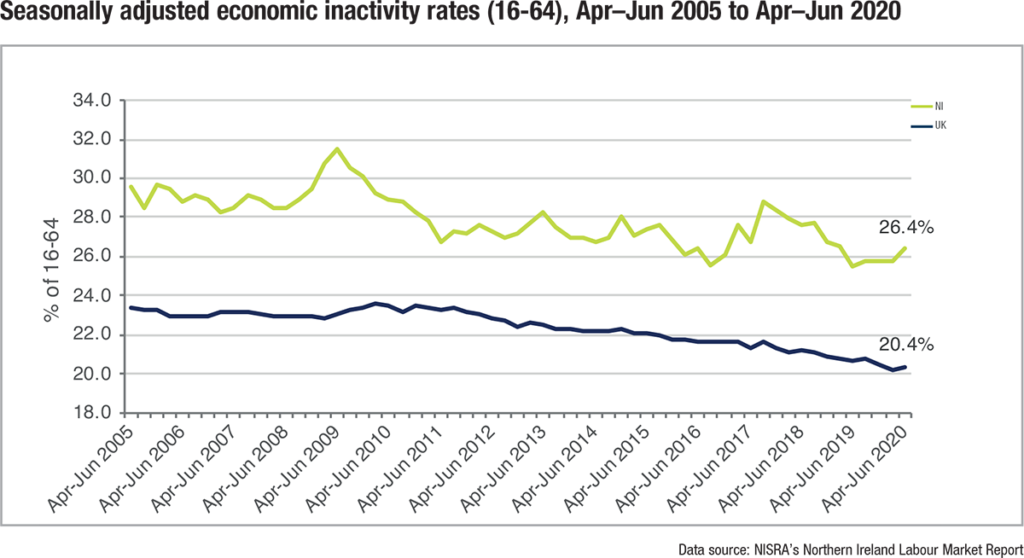

Northern Ireland’s improved unemployment rate and economic inactivity figures, while often cited by politicians, have long been recognised by economists as lacking the ability to paint a holistic picture of the real state of the region’s labour market. Most notably, falling levels of unemployment fail to reflect a well-recognised productivity gap in Northern Ireland. The region is a laggard in productivity when compared to the rest of the UK, which is itself a laggard compared to many of its European counterparts.

The strength of Northern Ireland’s Labour Forces Survey lies not in its ability to reflect the status quo, as evidenced by the fact that it failed to offer an indication of the severity of the 2008 financial crisis until the recession was well underway, but that its backward-looking nature offers an opportunity to assess the shape of the labour market as the pandemic began.

In brief, prior to the pandemic record levels of unemployment and improved economic activity rates represented a fairly stable position, however, failure of wage recovery from 2008, significantly below UK levels, and an increase in more precarious forms of employment were noticeable weaknesses as measures were taken to contain the virus.

August’s Labour Market Report by NISRA presented a more indicative outlook on how the labour market will be shaped by the measures introduced to contain the virus and the efforts for recovery. However, it is widely understood that the true impact will not be recognised for some time, largely because of the UK Government’s Job Retention Scheme (JRS).

The scheme was designed to prevent large scale redundancies during the economic slowdown and it’s estimated that over a quarter of a million workers were placed on furlough in Northern Ireland. However, with the scheme set to end in late October, it has also been recognised that many businesses will reduce staff once government supports stop and some others will be unable to return as viable businesses. This combination will ultimately lead to a further spike in unemployment levels.

Already Northern Ireland’s claimant count is over 62,000 people, double what it was in March; these are levels that were last realised in 2012 and 2013. One slight anomaly in the statistics is that despite this doubling of the claimant count since March, the number of claimants actually fell over the month to June by 1,200. This can largely be explained by the introduction of further support measures by those workers, including some self-employed workers, not originally covered by the early government supports. The number of people on the Northern Ireland claimant count increased by 500 over the month in July 2020.

Also recognised is a dramatic fall in the number of hours worked across the economy. Furloughed workers alongside people working fewer than their normal hours have seen the average number of hours worked per week in Northern Ireland fall to the lowest on record (27.1 hours), a decrease of some 20 per cent over the year.

As a result of the economic slowdown, employers in Northern Ireland proposed almost 2,000 redundancies in July. An additional 163 were proposed in the first 10 days of August, meaning that almost 8,755 redundancies have been proposed since the 1 August 2019, the highest annual total since records began. The Department was notified of 610 confirmed redundancies in July 2020, taking the number of confirmed redundancies to 3,112 in 12 months to end of July; compared to 1,785 the previous year

These redundancies were concentrated in but not exclusive to the four economic sectors of retail, hospitality, manufacturing and transportation. No economic sector is expected to be untouched by the economic crisis, but it is recognised that some sectors will bear a disproportionate impact.

Noticeably, companies are only required to notify the Government when they plan to make more than 20 people redundant, meaning that the figure is likely to be much greater, even with the JRS still in place.

Worrying for the Northern Ireland economy is that not only are unemployment figures set to rise sharply but that the economic inactivity rate (those aged 16 to 64 who don’t work and are not seeking or available to work) had already increased by 0.6 per cent over the quarter to July and almost 1 per cent over the year. Northern Ireland’s current economic inactivity rate of 26.64 per cent is significantly higher than the UK average (20.4 per cent) and this has been recognised as a major barrier to bridging the productivity gap.

Wages also fell for the first time since 2015. The median monthly pay of £1,681 for Northern Ireland employees for the three months to June 2020 represents a 0.8 per cent increase on the same period for 2019 but tellingly, the 1.5 per cent decrease from the previous quarter is the second consecutive quarterly decrease, before which none were recorded since 2015.

While these figures offer a sense of the forthcoming impact on the labour market by the introduction of measures to restrict the spread of Covid-19, it remains too early to fully assess the scale of the economic damage on the Northern Ireland economy caused by the pandemic. Undoubtedly, levels of redundancies will increase, and this will bring about an increase in the unemployment rate and subsequently, a decrease in the employment rate.

By what levels these figures will change depend largely on the ability of the private sector to respond. In April, the Northern Ireland Chamber of Commerce conducted a survey which stated that around 40 per cent of businesses in Northern Ireland have no or less than one month of cash reserves. Such a figure is telling when trying to estimate the ability of businesses to commence operations back to normal levels, or any level, once government supports end.

The length and severity of the economic shock will determine the future outlook of the labour market.