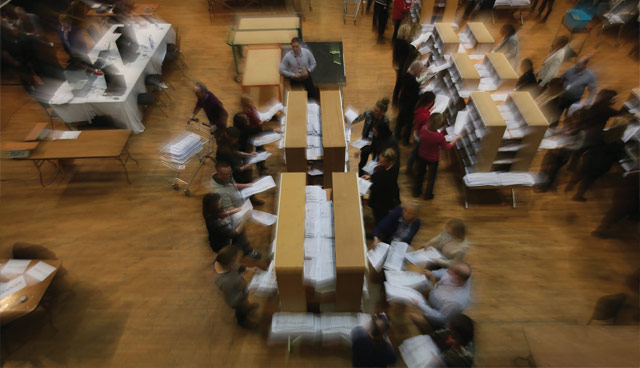

Local elections 2019

The political landscape in Northern Ireland has dramatically changed since 2014, the last time the electorate were asked to choose their representatives on reformed local authorities.

In 2014, the local government elections were carried out in the context of significant reforms to local authorities including the creation of 11 new look ‘super’ councils with additional powers around areas such as planning, urban regeneration and community development. While the outcome painted a familiar picture in terms of party popularity, with the DUP returning the most councillors (130) followed by Sinn Féin (105), the context was an evident declining nationalist turnout and gains by the UUP and TUV at the expense of DUP votes.

At the time, many pointed to emerging frustrations in the delivery of government as possible reasons behind the declining nationalist turnout or UUP and TUV increases. Five years on and it’s hard to take any lessons from 2014 and apply them to an assessment for May’s outcome. Two subsequent Assembly elections have highlighted a significant change in the nationalist turnout at the ballot boxes and significant declines for the UUP and SDLP mean that it is likely the that the DUP and Sinn Féin will further consolidate their dominant positions.

The TUV’s gain of 13 seats in 2014 is likely to be hard-fought by the DUP, who will be seeking to regain them. Similarly, the UUP’s electoral decline since those 2014 elections means that it is highly unlikely they will retain that level again. On the nationalist side, Sinn Féin’s seats appeared to go to minority parties or independent candidates rather than the SDLP, as would have been expected. Many of the minor parties will cite the absence of the Assembly as reason that they have not been able to grow their voter base to levels they had previously aimed, given that Assembly profile of party members usually has a positive trickle down effect to local level. Whether or not the range of over-arching issues, not least Brexit, will benefit or hinder independent candidates remains to be seen but it appears likely that Sinn Féin will eat into the SDLP’s current holding, if 2017 electoral trends at Assembly and Westminster level are to continue.

The same logic applies for those smaller parties. The Green Party have recently changed their leader and deputy leader, with Clare Bailey announcing her decision to step down as deputy leader, only to come back and take the position as leader a year later. The reconfiguration might have an impact on the party’s vote share but any change is expected to be minimal. The enthusiasm that once surrounded People Before Profit, especially the election of Gerry Carroll as their first council representative and later first MLA, also appears to have waned as evidenced in the 2017 elections.

The Alliance Party stand to take advantage of the current political context. The party have been longing for a significant boost to their vote share in hope that it will add further credibility for a move away from the green and orange track record of the politics in Northern Ireland. However, failure to secure a sizeable increase could be viewed as a failure on their part given that theoretically, voter disgruntlement with the big two should be at an all time high in the context of no working Assembly and the ongoing uncertainty around Brexit.

Brexit and the Assembly are likely to be two issues that meet candidates on the doors of voters before the elections of the 2 May. However, with local authorities having little influence over either, it’s unlikely that either issue will cause a dramatic shift in the voting trends. Similarly, the final report on the RHI scandal now looks unlikely to be released before the polling date, something others had predicted could have had a large sway on the public’s mindset and even turnout.

As well as a number of over-arching political themes there are also some changes at local level which could impact on the outcome. Going back to 2014, the emergence of NI21 as a new middle ground alternative, represented a new avenue for voters. Although the party’s success was limited to one council seat, NI21 contested in eight district electoral areas and gained over 11,000 first preference votes which are now up for grabs.

The emergence of Aontú, former Sinn Féin TD Peadar Tóibín’s pro-life Republican party, is likely to have an impact on the nationalist party vote share. How the party will be received is unclear but with the announcement of 17 candidates to date in Northern Ireland, their involvement will undoubtedly redistribute some votes.

The SDLP are also presenting themselves in a somewhat different package. Their formal partnership with Fianna Fáil ended speculation of the latter running candidates in Northern Ireland but the relationship also caused turbulence within the SDLP. The party lost only one MLA to the partnership, when it was expected that number could have been bigger and at local level, any dissention has been largely voiced in-house. The SDLP appear confident that the deal will bolster their appeal on the doors.

Not to be underestimated is the influence of non-politics on local government elections. Since 2014, councils across Northern Ireland have made significant strides in embracing their increased powers in attempts to drive local economies. In the absence of Stormont, work in areas such as the development of local action plans, digitisation of public-facing services and area regeneration could raise the awareness of the importance of Northern Ireland’s only functioning level of government.

Similarly, reputation is always a factor. Not only in terms of a councillor’s ability to deliver for constituents but also in terms of the quality of representatives. The absence of Stormont has already seen reputable former MLAs such as Danny Kinahan and Eamonn McCann revert back to local level politics and the same logic applies to those candidates whom, had Stormont been running, may have already been catapulted to MLA status but who now see greater prospects at local level.