Life after Labour

John O’Farrell reviews the record and recalls an old but perhaps relevant socialist critique.

John O’Farrell reviews the record and recalls an old but perhaps relevant socialist critique.

How will Labour deal with opposition? The best way of attending to that question is to ask another: How did Labour deal with government? The next generation of Labour’s leaders will have to honestly address the successes and failures of their 13 years – and then to address the things they did not do but should have done.

An audit can be carried out, balancing the good and the bad. Non-violent crime decreased, wealth increased, more people are healthier and better educated, legal and social attitudes have improved for gays and ethnic minorities. But at the same time, the wealth gap widened, swathes of public services were flogged off to corporations, social life contracted into the home as pubs and clubs and libraries closed, obesity and STDs increased, violent crime rose, and the most controversial foreign policy act since Suez split the country and tarnished the memory of Tony Blair forever in the public mind as a war criminal.

It will take generations for Iraq to be cleansed from Labour’s system, and all of the rest of Blair’s peacemaking efforts and humanitarian interventions (Kosovo, Sierra Leone, Northern Ireland) will remain lost in the fog of the Iraq War. Partly as a result of the tales spun to the public in the case for war, and the later revelations of the expenses system for MPs, trust in and from the public has eroded to quite dangerous levels. In 1997, 40 per cent of the British public agreed that “Britain is becoming a worse place to live.” By 2008, 71 per cent agreed, despite being asked at the pinnacle of the boom.

Another, but related problem for Labour was and is how much they could take their core supporters for granted. Cameron and Clegg have that problem now, but for all the rhetoric about being “at our best when we are at our boldest,” the problem was Blair’s and Brown’s timidity in the face of unelected power.

This was as much of a problem for Harold Wilson 45 years ago, when he was on the receiving end of screeds such as this: “Governments may be solely concerned with the better running of ‘the economy’. But the description of the system as ‘the economy’ is part of the idiom of ideology and obscures the real process. For what is being improved is the capitalist economy; and this ensures that whoever may or may not gain, capitalist interests are least likely to lose.”

The same critic argued that the problem was personal, as well as political: “In an epoch when so much is made of democracy, equality, social mobility, classlessness and the rest, it has remained a basic fact of life in advanced capitalist countries that the vast majority of men and women in these countries has been governed, represented, administered, judged, and commanded in war by people drawn from other, economically and socially superior and relatively distant classes.”

The above quotations were not drawn from recent analyses such as The Spirit Level, or the work of academics and commentators such as Danny Dorling, Richard Murphy, Amartya Sen, David Blanchflower, Polly Toynbee or Nick Cohen, who succinctly summed up the new cabinet of the New Politics thus: “Look hard at a picture of our new government, and you could be forgiven for thinking that the 20th century never happened.”

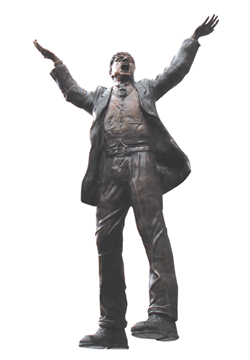

The above analysis of the workings and permanence of the UK’s “power élite” was written in 1968 by Ralph Miliband, who had fled the Nazis as a triple target. He was a Jewish Marxist intellectual and became a key figure in the British New Left through works such as The State in Capitalist Society, from where those quotations originated. At the time he was writing those words, his son David was about to start (state) school, while Ed was still a twinkle in his father’s eye.

If as seems likely, one (or both, somehow?) of the Miliband brothers assume the mantle of loyal opposition to the ConDem coalition, they may wish to retrace the journey they have made from the views expounded by their father, who died in 1994. Because when one looks back on Labour’s record, the fact remains that the one issue of national importance which remained so unchanged that it was almost a hidden, even taboo, subject was class.

By the end of Labour’s reign, the spending power of the wealthiest 10 per cent of the UK is 100 times the spending power of the bottom 10 per cent. That is immoral, inefficient and unsustainable, and makes a mockery of the very name of the ‘United’ Kingdom.