Lessons from academic selection

Northern Ireland continues to retain a virtually unique system of testing for the transition between primary and post-primary education. agendaNi examines academic selection.

Academic selection has been a source of contention since the Education Act (Northern Ireland) 1947 which followed the lead of the Conservative Government’s implementation of selective post-primary structures in 1944. However, the North never made the shift to adopt a comprehensive system like that which became prevalent in England and Wales. As such, the selective framework remained relatively unscathed for 50 years, until the Labour landslide in 1997.

The Labour Government’s Minister with Responsibility for Education, Tony Worthington, subsequently instigated two major research projects into the impact of selection. Upon publication of Tony Gallagher and Alan Smith’s ‘The effects of the selective system of secondary education in Northern Ireland’ in 2000, Education Minister Martin McGuinness established a Post-Primary Review Body to consider potential structures for post-primary education.

The Burns Report was published by the body, chaired by Gerry Burns, the following year. Core to the report’s recommendations was the abolition of the 11-plus transfer test. After a consultation, the results of which were published days before the 2002 Assembly suspension, McGuinness announced the elimination of transfer tests. During this suspension, Jane Kennedy, the direct rule Minister with Responsibility for Education, established a Post-Primary Review Working Group to weigh up options. In late 2003 the group produced a report and its recommendations were fully implemented by Kennedy.

As recommended in 2001, the transfer tests were to be replaced with parent and pupil-centred decisions, informed by a pupil profile (which would help inform parents on a child’s progress). In addition to this, an Entitlement Framework would be introduced to offer a broader, economically relevant curriculum.

In 2006, the Labour Government introduced the Education (Northern Ireland) Order which included provision to inhibit Board of Governors from implementing admission criteria which included academic ability as a consideration. Later, during the St Andrews negotiations, Tony Blair would amend these provisions so that a renewed administration could make a decision on selection.

In 2008, following the restoration of devolved powers, new Education Minister Catríona Ruane submitted proposals to abolish academic selection. The proposals were not debated by the Executive and a final cohort of primary pupils sat state-sponsored tests in November that year.

Departmental policy

In the vacuum left by the absence of a regulated approach, the Department of Education produced guidance for the transition between primary and post-primary. There were four key features to this policy:

- schools had a statutory requirement to admit applicants to all available places;

- decisions on admission could not correlate with academic ability;

- recommendation was made for priority to be given to pupils entitled to free school meals (FSM), as well as for those with a sibling at the school, applicants coming from feeder schools and applicants residing within a local catchment area; and

- a requirement that primary schools adhere to the statutory obligation to deliver the curriculum and refrain from facilitating unregulated tests in any format (including supplying materials, coaching within core teaching hours, offering afternoon tutoring or familiarisation with a test environment).

However, as of September 2016, the Department’s policy has inverted upon itself. Minister Peter Weir’s revised guidance now authorises schools to facilitate unregulated transfer testing. Specifically, schools are presently permitted to:

- supply supporting materials relevant to the tests;

- conduct preparation for the tests during core teaching hours;

- instruct children on exam technique;

- support the tests logistically; and

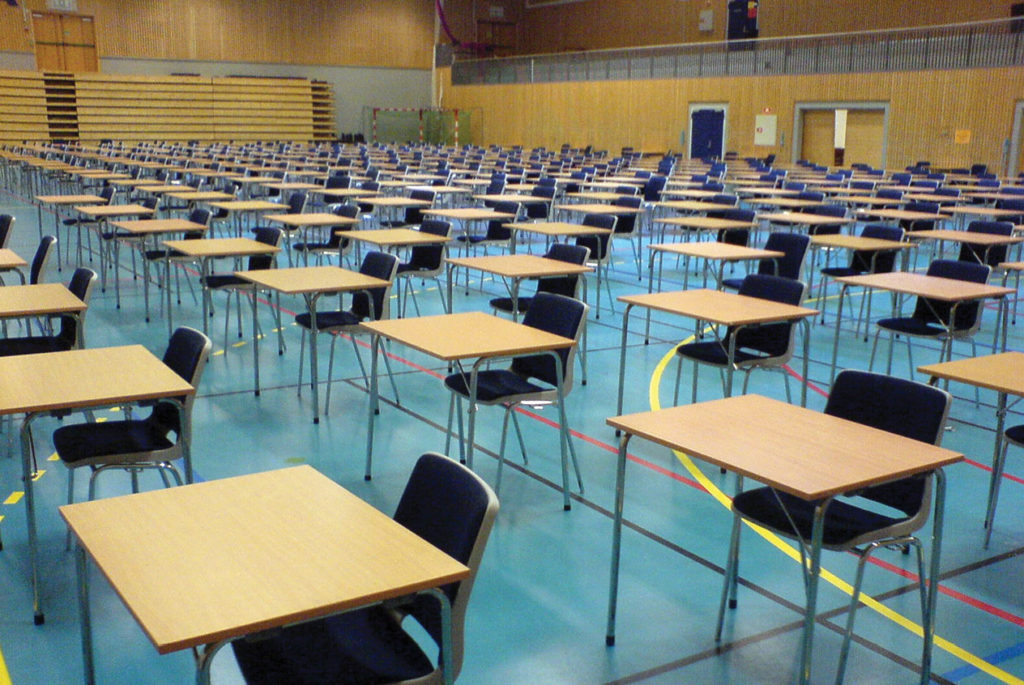

- familiarise pupils with examination environments.

Weir’s policy has also eliminated the provision which prohibited academic ability from informing the decision making process related to admissions. The Department’s policy states: “[It] supports the right of those schools wishing to use academic selection as the basis for admission.”

“Minister Peter Weir’s revised guidance now authorises schools to facilitate unregulated transfer testing.”

Two organisations, the Post-Primary Transfer Consortium and the Association for Quality Education, currently provide access to unregulated academic selection on a commercial basis. Although the respective GL and AQE examinations are purported to correlate with Key Stage 2 maths and English, both face a significant level of critique.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have expressed concern. As there is no guarantee that these tests adequately align with the knowledge and skills based curriculum, the OECD maintains that they are a prime example of commercial tests “driving and possibly distorting the curriculum”. OECD research also records that primary schools had previously reported parental pressure to ignore official policy and use core teaching time to prepare pupils. In a keynote address to the Association of Educational Assessment Europe in Belfast, prominent academic Jannette Elwood expressed a scepticism that the unregulated tests were of sound validity, reliability or comparability.

Similarly, an unpublished Office of the First and Deputy First Minister commissioned report, leaked to the BBC late last year, recognises that while excellence exists within the system, there is a gulf in terms of equity. Investigating Links in Achievement and Deprivation (Iliad) is the culmination of a three-year study conducted by 10 academics from Queen’s University Belfast and Stranmillis University College. The research rationale aimed to determine the micro-complexities of Northern Ireland in relation to a wider correlation between deprivation and educational underachievement. More specifically, why children in highly deprived areas traditionally regarded as Catholic outperform, often significantly, their Protestant counterparts.

Debate

Significantly, the Iliad study recommends “the ending of the current system of academic selection” as a key measure to halt educational disadvantage. The report also forewarns: “Given the in-built and distinct advantage of a grammar school education and the significant political and lobbying influence of the grammar sector, opposition to radical change is expected.”

Conversely, advocates of academic selection often point to the success of Northern Ireland’s top-performing students ahead of those in other United Kingdom regions. Education Minister Peter Weir contends: “Grammar schools can, by setting demanding standards and offering rich educational opportunities, secure impressive outcomes for those who will derive the greatest benefit from them.”

However, at the opposite end of the spectrum, the reality is that a significant number of students are outstripping their UK counterparts in terms of underachievement. In fact, as of 2013, the percentage of students achieving the GCSE threshold (five good GCSEs) across the four main regions has been lowest in Northern Ireland. Excellence at the apex of results has served to mask a chronic underperformance at the base.

There is also a perception among parents that the unregulated tests possess a degree of prestige due to the fact that they act as gateway into particular academically high-performing schools. This has been illustrated through the comments of Minister Weir who suggests: “The prospect of getting into the grammar school, and the opportunities that it creates, encourages aspiration in our children and their parents.” He adds: “Through the selection process, grammar schools have been an essential vehicle for social mobility.”

Meanwhile, Protestant boys from deprived backgrounds (those with free school meal entitlement) remain among the top three academically underperforming groups across the UK. Only 19.7 per cent of these students received five good GCSEs (including English and maths), a proportion which contrasts significantly with the Northern Ireland average of 62 per cent. The distribution of students between grammar and non-selective schools starkly reflects socio-economic division. Of the 2015/16 cohort of post-primary beginners with free school meal entitlement, only 17 per cent enrolled in a grammar school. Within two-thirds of grammars, less than 15.1 per cent of pupils are entitled to free school meals. All non-selective schools are above this bracket.