Is the economy finally turning the corner ?

Kerry Houston and Alan Mitchell present Oxford Economics’ updated medium-term forecast for the Northern Ireland economy. Export-led growth must be accompanied by a domestic stimulus and the Executive must design a solid Plan B before the Prime Minister makes his decision on corporation tax.

Kerry Houston and Alan Mitchell present Oxford Economics’ updated medium-term forecast for the Northern Ireland economy. Export-led growth must be accompanied by a domestic stimulus and the Executive must design a solid Plan B before the Prime Minister makes his decision on corporation tax.

The Northern Ireland economy has endured one of its most challenging periods since the Second World War, with climbing unemployment, falling job numbers and tumbling house prices. Though recent headline indicators suggest some improvement in local economic conditions, it is too early to confirm whether a sustained recovery is under way.

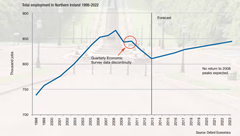

The striking feature of the latest Oxford Economics forecasts is the length of time estimated to recover recession job losses. According to workforce jobs employment data, Northern Ireland has lost 66,000 jobs between 2008 and 2013. However, the labour market outlook for Northern Ireland is relatively weak with only 28,000 jobs forecast over the decade ahead thus raising the question of: “What is needed for a more robust recovery of the Northern Irish economy?”

The outlook is centred on export-led growth. However, Northern Ireland’s relatively small export base is likely to hamper the pace of the growth. Export growth alone is insufficient for recovery in both output, and even more so, employment. Policy-makers may also need to look at how to stimulate the other elements of business demand and perhaps provide a stimulus to encourage consumers, business and government to play a bigger role in the recovery.

The outlook is centred on export-led growth. However, Northern Ireland’s relatively small export base is likely to hamper the pace of the growth. Export growth alone is insufficient for recovery in both output, and even more so, employment. Policy-makers may also need to look at how to stimulate the other elements of business demand and perhaps provide a stimulus to encourage consumers, business and government to play a bigger role in the recovery.

A long climb back

Job losses from 2008 onwards have been dominated by the construction sector, which has contracted by over 40 per cent driven by the bust in the local housing market. Retailing added to the recent gloom as many of the high street stores succumbed to the recession, shedding 12,000 jobs. Energy and perhaps rather surprisingly, given its dependence upon consumer spending, the arts and entertainment sector were the only private sectors to enjoy net job growth since 2008. Overall, 66,000 jobs have been lost in Northern Ireland since 2008.

The scale of the recession hangover is clear from Oxford’s latest forecast which suggests that it will be beyond 2023 before there are as many people in work as there were in 2008 with considerable downside risks attached to this central case. This has been revised downwards since our autumn 2012 forecast as a result of revisions to the number of recession job losses, accompanied with revisions to the forecast. Looking ahead to 2023, administrative and support services (excluding public administration and defence) are projected to dominate in terms of employment growth, with professional services and retailing also contributing. Though manufacturing is expected to contribute positively to GVA growth, it is forecast to continue to shed jobs alongside public administration and defence as austerity cuts are enforced.

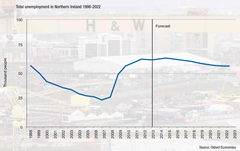

Recovery may be under way in technical terms but many individuals will remain in ‘recession’ for a lifetime. Despite a fall in claimant count over recent months, unemployment is expected to remain relatively high over the decade ahead, peaking at 65,000: a level similar to that experienced in the late 1990s. Unfortunately, the skills set of the people who lost their jobs may not be required by the sectors which are expected to lead the recovery, leaving many people out of work for an indefinite period.

Recovery may be under way in technical terms but many individuals will remain in ‘recession’ for a lifetime. Despite a fall in claimant count over recent months, unemployment is expected to remain relatively high over the decade ahead, peaking at 65,000: a level similar to that experienced in the late 1990s. Unfortunately, the skills set of the people who lost their jobs may not be required by the sectors which are expected to lead the recovery, leaving many people out of work for an indefinite period.

There remains to be potential for a further rise in claimant count unemployment as welfare reforms continue, with some claimants being transferred from long-term benefits to employment and support allowance (with the probable reduction in the amount of benefit). Our scenario analysis suggests that the level of unemployment could easily reach 80,000 as a result of welfare reform. This could reduce consumer spending and exert downward pressure on earnings for low skilled jobs as more compete for scarce job opportunities.

Alarming spatial problems

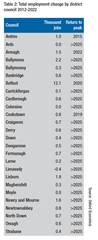

At the local level, Oxford Economics’ forecasts are worrying, particularly for areas outside the core urban centres. Given that the outlook is heavily dominated by the private service sector, growth is clustered around city areas where the supply of skilled labour is readily available. A revival of manufacturing and the agriculture sector would be welcomed by many of the more rural areas which are estimated to face significant labour market challenges over the decade ahead.

This sits against a backdrop of significant impending changes in local government. The Review of Public Administration reforms, set to be introduced in 2015, will lead to the introduction of the 11-council model. A range of powers will be devolved from central to local government as part of the reform. However, the precise mechanisms for delivery are still being refined, and it is important to ensure clarity of roles and minimal disruption to (and duplication of) delivery in the short-to-medium term.

One of the most prominent transfers of economic power is the delivery of business start up and small business support services. This responsibility lies with Invest NI under the current structure and the transfer has been widely welcomed by local government.

How can this be used to boost economic growth? Arguably, councils should have a better local knowledge of key requirements to support fledgling businesses – such as suitable vacant property and local services – but do they have the contacts in the longer term to support exporting if or when the new company requires it? Similarly, many councils will feel they have a direct role to play in the attraction of FDI to their respective areas, alongside being best placed to support local businesses in the export market.

Invest NI will retain the prime responsibility for attracting FDI to Northern Ireland and its remit will remain centrally focussed with no local targets. A wholly co-operative relationship between Invest NI and local councils is to be strongly encouraged and likely to be the most fruitful for Northern Ireland in the longer term. Global competition is simply too fierce for 11 council areas to be competing against each other. Such an outcome would not be favourable for the Northern Ireland economy and as such, a holistic approach is required.

The post-RPA environment is still relatively unknown – roles and responsibilities have largely been assigned but there is no hard evidence on the impact it will make on economic growth. Therefore, we must remain circumspect with regard to what, if any, impact it will make on alleviating the clear pressures on the majority of Northern Ireland’s localities, as highlighted in Table 2.

The post-RPA environment is still relatively unknown – roles and responsibilities have largely been assigned but there is no hard evidence on the impact it will make on economic growth. Therefore, we must remain circumspect with regard to what, if any, impact it will make on alleviating the clear pressures on the majority of Northern Ireland’s localities, as highlighted in Table 2.

Consumers and business

Consumer spending has consistently disappointed since the onset of the financial crisis, hampered by a severe squeeze on real wages and the need to deleverage. While the level of resources available to households is the key determinant of consumer spending, a number of other factors are also important. Wider labour market developments are significant, not just directly through their impact on household incomes but more indirectly through their impact on confidence. Given that we are unlikely to see a sudden correction in the labour market, consumer spending is likely to remain muted over the short run.

The fortunes of the housing market are also an important factor underpinning consumer spending. It is clear that increased housing activity tends to boost spending on goods related to moving house, such as furniture, carpets and white goods. House prices in Northern Ireland are reported to have experienced annual growth for the first time in more than five years which is welcome news. However, many home-owners are in negative equity and now face the prospect of a rise in mortgage payments, as interest-only mortgage periods have expired. This could potentially cause further difficulties for the market. Interest rates should remain at historical lows over the short run as the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee will be aware of the risks associated with increasing households’ debt servicing costs, so any tightening of policy is likely to be very gradual.

Overall consumer conditions are improving and consumers should start to make a positive contribution to growth, but there will continue to be bumps ahead. It will be 2015 before spending returns to pre-crisis levels.

For investment, addressing structural problems in banking and property are essential long-term measures although in the short term tackling these problems could actually constrain lending and investment further.

The policy challenge

The scale of the policy challenge is clear both sectorally and spatially, with RPA – whilst welcome – unlikely to be enough on its own. The ‘policy neutral’ outlook is for job growth to average 2,500 per annum over the decade ahead, which keeps the employment rate at a disappointing 54 per cent (as a percentage of the population aged 16 and over).

By way of scaling the problem, to get the resident employment rate to the UK average of 58 per cent in 2023 would require over 8,000 additional jobs per annum or an additional 62,000 in total.

By way of scaling the problem, to get the resident employment rate to the UK average of 58 per cent in 2023 would require over 8,000 additional jobs per annum or an additional 62,000 in total.

To date, Northern Ireland economic policy has largely been ‘business as usual’ despite the drastic change in economic conditions. A key current decision for the Executive is what to do in economy policy terms between now and autumn 2014 when a decision on corporation tax is expected. Sitting and waiting should not be an option, nor an outcome accepted by Northern Ireland’s citizens and businesses.

There have been some noteworthy policy ‘successes’. Some of these are directly attributable to the Executive and some have been gifted from elsewhere. For example, Northern Ireland’s allocation of the EU Structural Funds for the period to 2020 will be € 457 million, down only 5 per cent from the previous period.

This is a steeper decline had been expected but Westminster allocated the funds favourably towards Northern Ireland and other devolved regions. Whilst this impact is less substantial in the grander context – the gap between tax receipts and funding is around £10 billion – it is to be welcomed and should be maximised.

The economic package announced in advance of the G8 Summit and the special economic planning zones spliced onto the Planning Bill received a great deal of media attention but what does either really deliver for Northern Ireland?

The former welcomes applications for enterprise zones (amongst other things). Despite the usual degree of scepticism from economists (Oxford Economics included), this is another policy tool that –with the correct due diligence to mitigate the risk against displacement – has the potential to offer something to the Northern Ireland economy.

The latter – despite being politically controversial – paves the way for OFMDFM to take planning decisions in areas of strategic economic importance. In theory, this should lead to a time reduction in the planning process – a regularly cited irk of many. Notwithstanding the potential for abuse of the power, it is a bold move, highlighting that economic growth is indeed a key priority of the First Minister and deputy First Minister.

However, whilst the EU Structural Funds, economic package and special economic planning zones are all positive policy decisions and likely to support growth in the short-to-medium, even together they feel inadequate to support the level of economic growth, Northern Ireland needs in the longer term. Without a reduction in the rate of corporation tax or compelling Plan B, there is little to suggest from Northern Ireland’s economic base, economic policy ambition and appetite for real structural economic reform and tough decision-making, that the Northern Ireland’s economy can out-perform the UK economy, ride the crest of waves of new growth sectors, and be any better than a ‘2 per cent annual growth’ economy.

However, whilst the EU Structural Funds, economic package and special economic planning zones are all positive policy decisions and likely to support growth in the short-to-medium, even together they feel inadequate to support the level of economic growth, Northern Ireland needs in the longer term. Without a reduction in the rate of corporation tax or compelling Plan B, there is little to suggest from Northern Ireland’s economic base, economic policy ambition and appetite for real structural economic reform and tough decision-making, that the Northern Ireland’s economy can out-perform the UK economy, ride the crest of waves of new growth sectors, and be any better than a ‘2 per cent annual growth’ economy.