Inflation picture means Bank of England ‘needs a recession’

Economic forecasts say that UK GDP will now not reach its pre-pandemic levels again until the end of 2024, meaning an entire parliament with no growth at all, says Chris Giles, Economics Editor of the Financial Times.

The UK economy

“The UK’s position is pretty weak internationally,” Giles says, pointing to OECD data that shows that the UK economy is the only one to have contracted in GDP terms between Q4 2019 and Q3 2022 when compared with Germany, Japan, France, Italy, Canada, and the United States. “The US is having a real boom, with more than 4 per cent growth over that period, but the UK is the only economy not to have recovered its pre-pandemic level and it is likely heading into a new recession. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in the Autumn Statement thought the UK would not hit its pre-pandemic level until the end of 2024; a whole parliament with no growth at all.”

Internally, Northern Ireland is doing “best or close to best across the UK”, a performance that Giles does not attribute to the Protocol, but rather to the increased amount of government spending that has fuelled the UK economy in recent years. Northern Ireland’s greater dependence on public consumption when compared with Britain is “almost certainly” what is driving its “rather healthier position”, Giles explains.

The UK economy, Giles says, is suffering from a fusion of the economic challenges currently being experienced on both sides of the Atlantic. “The UK economy is suffering a little bit of the European problem – high energy prices and big supply shock – making us just poorer than we used to be,” he says. “And also, a bit of the US problem in that at the same time, we also have very low unemployment and an increase in inactivity, and so we have also got a bit of a domestic inflation problem, which is not seen in Europe but clearly seen in the US.

“Bank of England projections forecast inflation over 10 per cent for the next six months and then coming down it is quite gradual and only gets to the 2 per cent target in 2024, meaning there will be another period of households really feeling the pinch.”

“The outlook for economic growth has deteriorated sharply since March 2022. With that pessimism on growth, we are also seeing inflation expected to come down (in 2023) because we are expecting not to see continued rising in energy process and the big increases will fall out of the annual comparison. Bank of England projections forecast inflation over 10 per cent for the next six months and then coming down it is quite gradual and only gets to the 2 per cent target in 2024, meaning there will be another period of households really feeling the pinch.”

Inflation and wages

80 per cent of all products are currently rising at a rate higher than the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target, more similar to the US than the EU, meaning that there is ingrained inflation in the system rather than simply being a case of increasing energy prices.

“The inflation picture means there is more for the BoE to do, and it needs a recession,” Giles says. “It needs everyone to feel some pain, so that workers do not seek higher wages and companies do not seek to raise prices very rapidly.”

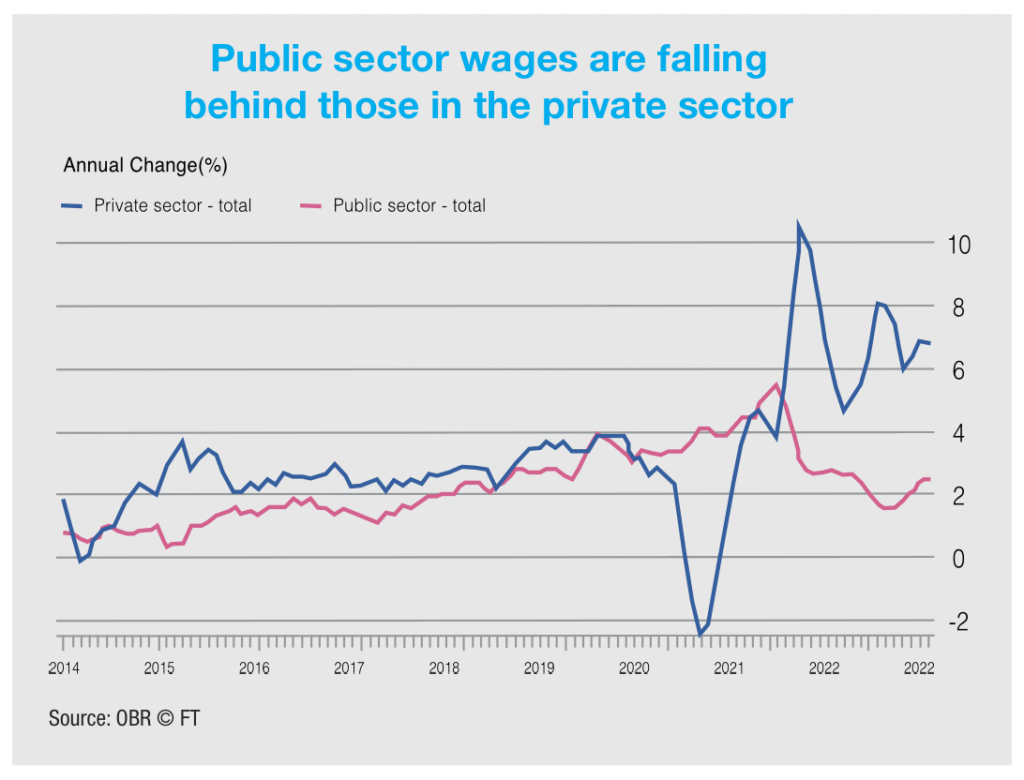

Private sector wages are currently rising at 7 per cent, lower than inflation at 11.1 per cent but higher than is sustainable for a 2 per cent inflation target. This is said to be “concerning” the Bank of England and is one the reasons interest rates are “certain” to rise from their current 3 per cent rate. Public sector wages, however, are only rising at a rate 2 per cent, creating an unsustainable gap between public and private wages.

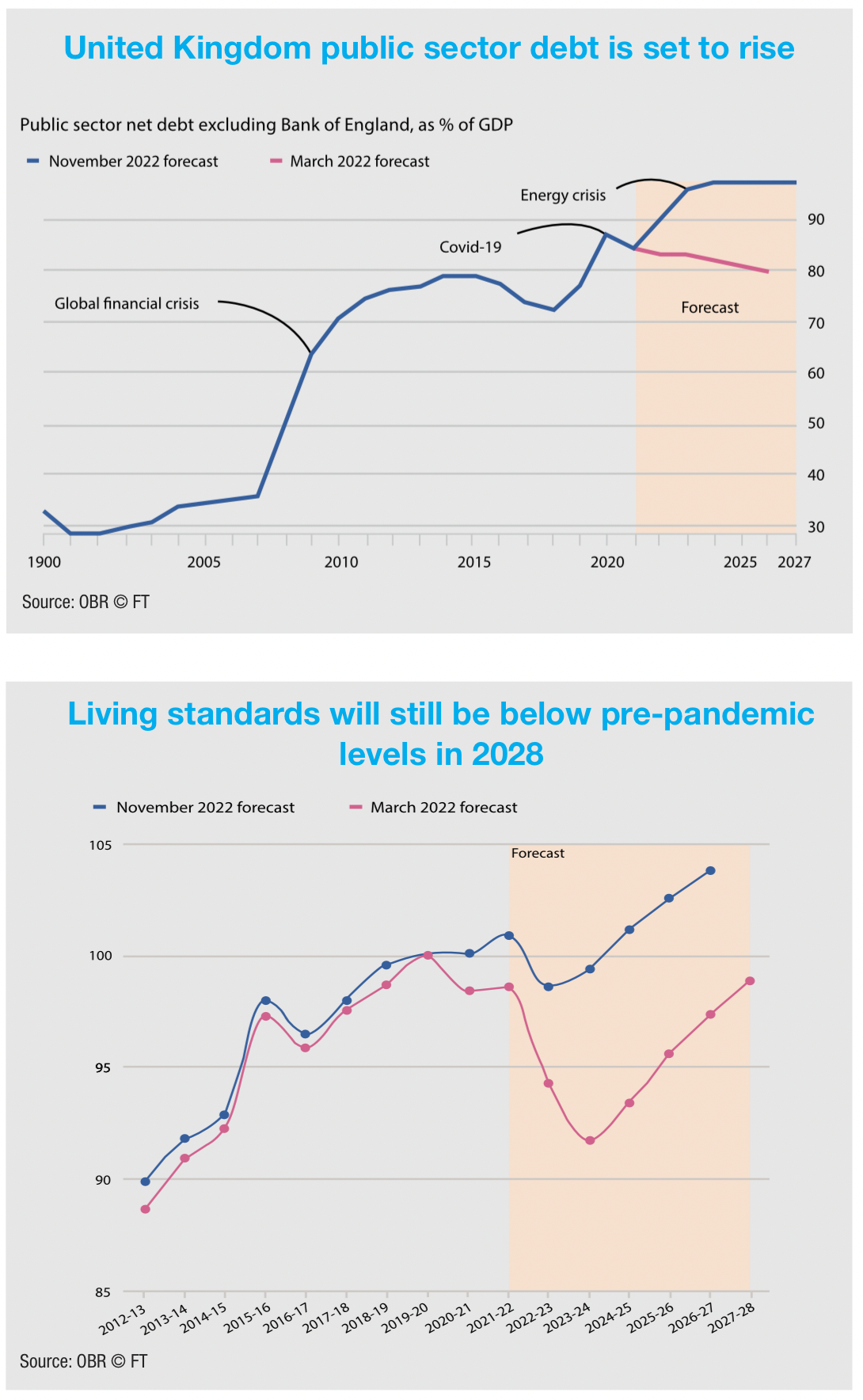

“The consequence of wages in total rising quite rapidly but too rapidly for controlled inflation is that living standards are falling and falling rapidly,” Giles explains. “The latest forecasts for household living standards are that we are likely to see a 7.1 per cent decline, the largest since records began, back to a level last seen in 2013. It is expected to recover but households are expected to go through a difficult period for 2023.”

Government finances

With household finances in difficulty, the same is true of government finances: from March to November 2022, the deficit forecast has increased from £30 billion to £80 billion. Driving this is higher debt interest spending, rising by £44 billion in just one year. “These are very large increases in debt interest. The State and all of us together are having to pay for government debt,” Giles says.

“The tax receipts are expected to be quite weak because the economy is expected to be weak. Welfare spending, particularly on pensions and other non-pension benefits, is likely to rise, again making the deficit worse, partly because inflation is high and the Government is going to pay increases in benefits according to inflation, but also a weak economy sees more welfare spending on unemployment and inactivity, particularly on disability payments at the moment.”

Offsetting those factors were some tax increases and spending cuts in the medium term, but even with tighter planned public spending after 2025, the level of borrowing is forecast to be much higher than expected as recently as March 2022.

“Debt is going to get very close to 100 per cent of GDP,” Giles says. “We used to think that it should not get above 40 per cent in the 1990s, all the way up to the financial crisis, but now we have had three ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ events one after another where government has had to borrow in the global financial crisis, the Covid-19 crisis, and the energy crisis.”

Gas prices

In attempting to combat the pessimism of the majority of current economic stats, Giles points to gas prices, which have fallen sharply, from €300 per MWh down to just above €100 per MWh. Reasons for such a notable drop include a concerted effort in Europe to conserve gas and to curb consumption – for example, German industrial consumption in gas is down almost 35 per cent on last year without a fall in output – and storage levels are now higher than any time in the last four or five years.

“In the UK, the energy crisis is likely over, and we had a self-inflicted crisis with the September 2022 ‘mini budget’ having the largest unfunded tax cuts in many years, which had a devastating effect on the UK’s borrowing cost,” Giles says. “Even that is now beginning to get better. With Liz Truss gone, we see the increase in the UK’s borrowing cost has fallen away. At the time of the mini budget, the UK was having to pay 1.5 percentage points more for its borrowing than usual. That is an enormous premium. There is scope to improve the public finances with the interest costs coming down in the future forecasts, which would make some of the austerity and tax increases not entirely necessary.”

In conclusion, however, Giles returns to a more a pessimistic note to reflect on the difficult times at present and in 2023: “There is no doubt that the year ahead is going to be very difficult. There will almost certainly be a recession, not necessarily a hugely deep recession, but it will not be the easiest time for the UK economy over the months ahead.”