Housing affordability crisis

As more low-income households are being pushed towards a private rented sector which cannot accommodate their needs, the state must shift back to playing a central role in supplying social housing for a broad range of households, argues Lisa Wilson, economist at the Nevin Economic Research Institute.

The housing circumstances in which one lives constitute an important aspect of one’s living standards, but they are also an important determinant of living standards. The impact of housing costs on living standards lies in the balancing of housing costs with other non-housing expenditures, within the constraints of one’s income. Unaffordable housing costs can negatively impact on living standards as households are forced to reduce their expenditure on other necessities such as food, clothing, and healthcare in order to keep a roof over their head.

Whilst several different approaches exist to assessing whether or not housing costs are having a disproportionate impact on living standards, the most commonly used approach is the ‘housing cost to net household income ratio’.

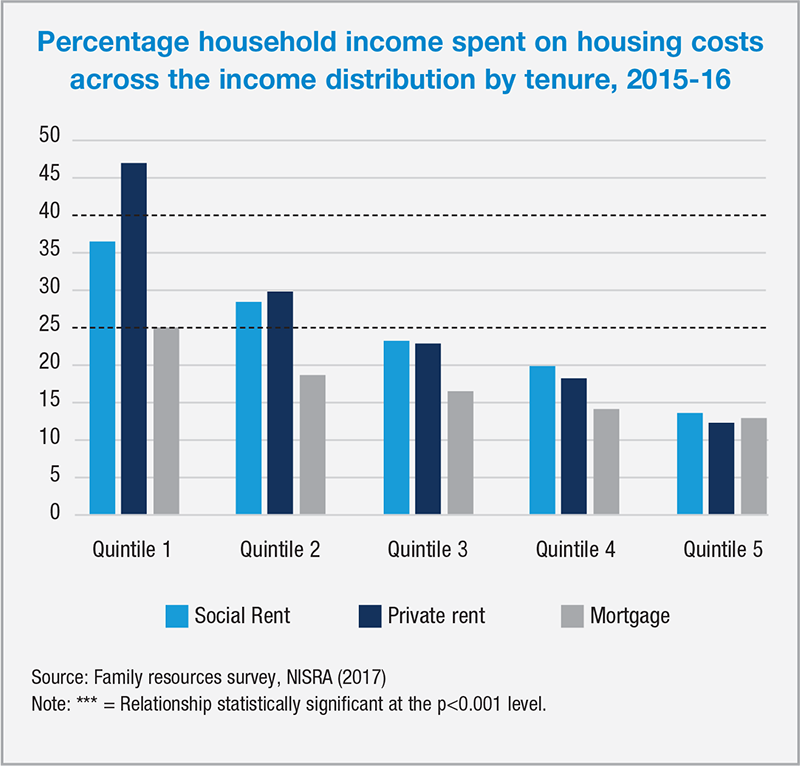

This approach sees housing costs as unaffordable or as having a disproportionate impact on living standards when the household spends over a certain percentage of their income on their housing costs. The setting of this ‘affordability threshold’ is not an exact science, but rather based on a normative judgement about what proportion of income should be spent on housing. Over time, affordability thresholds have varied between 25 per cent and 40 per cent, with households spending more of their income than this, identified as facing an affordability problem.

In utilising any one of these thresholds it does not appear, on the whole, that housing costs are having a particularly problematic effect on living standards in Northern Ireland. In fact, if anything housing in Northern Ireland looks fairly affordable and when measured against the other regions of the UK housing costs in Northern Ireland compare quite favourably.

Average measures, however, conceal important differences between different sub-groups of the population. Thus, whilst housing costs may be relatively affordable for much of the population in Northern Ireland, it is clear that there is some segments who face excessively high housing cost to income burdens.

One in three households in Northern Ireland spend 25 per cent or more of their household income on housing costs, while one in 10 households spend more than 40 per cent.

The percentage of income spent on housing costs is strongly influenced by tenure with those in the private rented sector being most likely to spend more than 40 per cent of their household income on housing costs, with close to one in six in the private rented sector doing so. This contrasts with just over one in 10 of those in the social rented sector and one in 20 of those who own their house with a mortgage.

The percentage of income spent on housing costs is also strongly influenced by household income. As demonstrated in the chart below, across all tenure types, housing costs exert a higher burden on lower income households. This is particularly the case for low-income households in the private rented sector.

Market rent

The reason for this is that there is not very much variation in terms of how much a privately rented property costs in rental fees, regardless of how low or high your income is. The poorest households spend £88 on average in private rental housing costs per week, whereas the richest households in the private rented sector spend £96. The household income of the poorest households in the private rented sector are however relatively quite low. The poorest 20 per cent in the private rented sector have an income of £188 per week. Thus, housing costs do not decline proportionally with income. The lowest income households in the private rented sector pay over 90 per cent of the median rent of the highest income households in the private rented sector, but only have an income of about 25 per cent as much.

You might be tempted from this to conclude that it is income that is too low and not housing costs that are too high. However, the lack of variation in housing costs in the private rented sector makes clear that there are limits that can be made in the quest to lower the housing cost to income burden for those with lower incomes. Market rent is market rent and private landlords are not in the business of ensuring that the poorest households have affordable housing.

The implication of this is that many low-income households are being pushed into poverty by their housing circumstance. There are close to 34,000 households in the private rented sector in Northern Ireland who are at-risk-of-poverty after housing costs because they simply cannot afford to pay private rents.

Given, however, that on the whole, housing costs in the private rented sector do not exert a particularly negative effect on living standards, it would appear that it is not rent levels in this sector which require policy intervention. Rather, it seems that there is a minority, but significant share of households who live in the private rented sector, who would perhaps be better placed in the social rented sector.

In fact, these are households who would have traditionally expected to find tenure in the social rented sector. Given the long-term trends of limited and decreasing supply in the social rented sector, it is possible that these are the households that have been left out. As the social rented sector has reduced in recent decades, it has had to concentrate on housing the most vulnerable and those with complex needs. It has become much more difficult to house those who are ‘just’ poor.

If current trends continue, there is a real danger that the housing system will continue to create poverty and deprivation as more and more low-income households are being pushed into a private rented sector which cannot accommodate their needs.

This has important implications for policy, particularly in the context of the ‘residualisation’ of the social rented sector, and the growth of the private rented sector for those with low-incomes. The social housing sector is quite successful at breaking the link between housing costs and poverty. The private rented sector, well that’s not its purpose.

So, what needs to be done? Solving the existing crisis in housing is not rocket science. There are real solutions that could be implemented if the political, societal and institutional will existed. At the very core of solutions is the requirement of the state to shift back to playing a central role in supplying social housing for a broad range of households ranging from the most vulnerable and those with complex needs to those who are ‘just poor’.