From 30 to 20 years

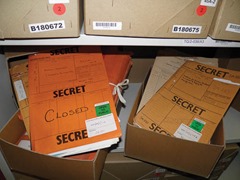

Archives will now be releasing much more information but officials and historians have claimed that more openness does not necessarily improve how government works.

Archives will now be releasing much more information but officials and historians have claimed that more openness does not necessarily improve how government works.

Government papers in the UK used to stay in the archives for 30 years before they were released but Gordon Brown questioned the need for this when he took office in 2007. “It is an irony,” he said, “that the information that can be made available on request on current events and current decisions is still withheld, as a matter of course, for similar events and similar decisions that happened 20 or 25 years ago.”

Brown commissioned an independent review of its working, led by Daily Mail editor Paul Dacre, which recommended a reduction to 15 years. Journalists were naturally pleased and civil servants perplexed. The Government settled on 20 years.

Two years of records will be released each year over the next 10 years (see table). A total of 1,047 files from 1983 and 1984 have been fully opened. Another 366 files have been partially opened or redacted. The remaining 225 are still fully closed.

The 30-year rule, though, will be kept for information that is considered “prejudicial” to the “effective conduct of public affairs” in Northern Ireland or to the work of the Northern Ireland Executive.

Most files for the peace process years will be released between 2018 and 2027. The most sensitive political papers, though, will only be released from 2028 onwards with some closed off for several more years.

This decision was made after lobbying from the Northern Ireland Office. Writing to the review, then Permanent Secretary Jonathan Phillips said that “the long conflict in Northern Ireland and the delicate nature of the settlement … mean that we have a large volume of unusually sensitive records”. Their early release “could cause real damage to relationships and hamper the embedding of the devolution settlement.”

The NIO’s undisclosed files contain “information given in confidence about negotiating positions within and between parties” and similar information about “the resolution of community disputes or measures taken discreetly to assist in building community confidence.” Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness complained that a 20-year rule would put “considerable strain” on officials.

A more nuanced criticism was made by the historian Anthony Seldon who wrote: “A shortening of this period will cause more problems than it will solve. It will not lead to better government and could lead to worse.” For historians, the “essential contours of contemporary history are known (largely due to interviews) long before the opening of the public records.”

The main reasons cited for keeping a file closed are health, safety and data protection. However, in most cases, secrecy has to be weighed up against the public interest which includes promoting accountability, transparency or fair treatment.

The Republic has a 30-year rule and may consider a reduction to 20 years in its new Archives Act, which is due to be enacted before 2016. The Dacre review

report and the evidence collected for his inquiry is available online at www.30yearrulereview.org.uk

| The transition years | |

| Recorded | Released |

| 1983 & 1984 | 2013 |

| 1985 & 1986 | 2014 |

| 1987 & 1988 | 2015 |

| 1989 & 1990 | 2016 |

| 1991 & 1992 | 2017 |

| 1993 & 1994 | 2018 |

| 1995 & 1996 | 2019 |

| 1997 & 1998 | 2020 |

| 1999 & 2000 | 2021 |

| 2001 & 2002 | 2022 |

| 2003 | 2023 |