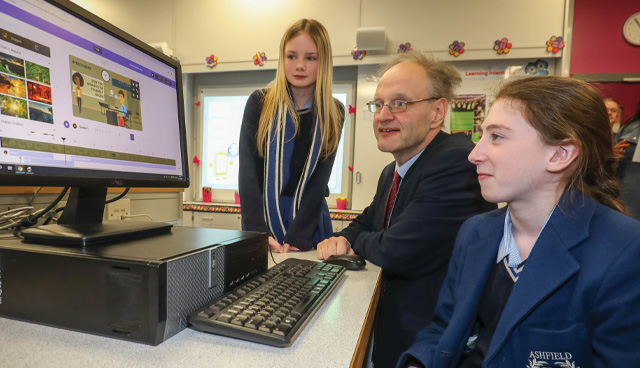

Evolution of education: Minister Peter Weir

In the week when most pupils returned to school following the unprecedented closure in March, David Whelan sat down with Education Minister Peter Weir to discuss his re-opening plans and assess the level of delay placed on the ambitious promises of the New Decade, New Approach agreement.

The return of devolved government in January was met with a level of optimism within the education sector. The agreement, signed by the five main parties, pledged radical reform across many sectors and outlined education as a key plank of many of the ambitions to improve the economy and society in Northern Ireland.

The education sector found itself in an advantageous position. While other departments worked to bring their new ministers up to speed, Weir, having served as Education Minister prior to the Executive’s collapse, was well versed in the transformations required and the steps needed to initiate it.

Fast forward just a few months and the course of those ambitions was altered radically when the scale of the potential impact of the pandemic was signalled by the decision to close all schools.

After much deliberation, weighing up the risk to public health against the recognisable detriment to children’s education, Weir, fresh from visiting a number of schools following the decision to bring all pupils back, describes a “high level of eagerness” among parents, pupils and teachers.

“Obviously, there will be some concerns, which is understandable, but in general I think that people have embraced this enthusiastically and energetically.”

On school preparedness for the return, he says: “What I have been impressed with is not just the application of the guidance but the level of thought that a lot of schools have put into this. Every school is different and so there is no one-size-fits-all model but I’ve been very conscious during visits of the effort and detail that has been put into a range of issues, such as staggered break times and movement around the schools, for example.”

In late August, over 100 Coronavirus cases were identified in one day, the highest daily rise since May, which brought a warning from the Health Minister Robin Swann that Northern Ireland was in danger of losing its grip on the virus. Questioned on what has changed in terms of public health safety since the decision to close all schools, Weir responds: “In March we were reacting to an unprecedented situation and so, the strong reaction across everything in society was probably the right response at that particular time. However, as time has moved on, it’s about how we could adapt ourselves to cope with the situation of the virus.

“I think it’s also a fact that the position of children being out of school and having some form of remote learning is a short gap measure. I don’t think it’s sustainable from a long-term educational point of view. I think there is a realisation, shared across the Executive, that ensuring our young people have the best start in life and are protected for the future is critical.”

While Weir believes it would be “foolhardy” to rule out a circumstance where the full closure of schools is necessitated in future, he adds: “The Executive, the Chief Medical Officer and I have made it clear that if we need to take various actions to combat Covid then the closure of schools would be the last resort. What will be the case is that we will get incidents within schools and with the guidance and help of public health, schools will need to react.”

New Decade, New Approach

Turning to the lofty promises set out in the New Decade, New Approach agreement for education and the knock-on effect of a shift in focus to managing the pandemic, Weir says he does not believe the ambitions have been set back but concedes that delivery or implementation “will have been dented”.

“A lot of things that, while important and desirable, were not something that had to be happening in that particular moment had to be temporarily set aside both in terms of the ability to actually deliver and because in the Department and the Education Authority we had to target staff at the immediate crisis of Covid.”

At the top of Weir’s in-tray in January was the promise to “urgently resolve the current teachers’ industrial dispute”. In April, teachers backed a pay deal from the Department which included up to the 2018-19 year and paved the way for discussion to begin for the 2019-20 and 2020-21 years. The deal, which broke the public sector pay gap, “addressed the losses against inflation” and was “benchmarked against neighbouring jurisdictions”, according to the Minister for Finance Conor Murphy. A noticeable challenge facing future negotiations is the announcement in July by Prime Minister Boris Johnson that teachers in England are to get a 3 per cent pay rise, although recognisably this is to be paid from the existing school budgets.

“The immediate element identified in New Decade, New Approach was that there was a dispute which had been hanging over for a number of years. Because of funding made available through the Executive to the departmental budget, we were able to resolve that. I think it’s more problematical moving forward with very tight budgets but there will be discussions that take place with trade unions.

“I think the problem with the much-vaunted increase over in England is that on the face of it no additional money was being made available. There is no point saying we will give money to something if there isn’t money to be given but there will have to be a lot of work done to see what can be done, working alongside management and the trade unions as we move ahead.”

The Executive, the Chief Medical Officer and I have made it clear that if we need to take various actions to combat Covid then the closure of schools would be the last resort.

Weir indicates that discussions on pay are set to resume in September and stresses a “fairly rapid” move to look at a number of workstreams identified in the resolution that weren’t immediately enacted during Covid restrictions.

Probably the most pressing pledge made in the NDNA agreement was action to ensure “every school has a sustainable core budget to deliver quality education”. The financial pressures on some schools were highlighted in the absence of functioning government. In 2019, schools in Northern Ireland overspent on annual budgets by more than £62 million, with more than 450 schools going over budget.

Outlining that the achievement of the ambition cannot be reached by a single action, Weir points to the securing of additional resources within the 2020/2021 budget which led to an increase in aggregated schools budgets and an increase in the AWPU (the age-weighted amount a school receives for each pupil).

“I think there has been a large gap between what schools have and what they need,” he states. “The actions at the start of the year will have narrowed that gap but certainly not closed it and the problem which we are trying to assess and obtain resources for is the extent to which Covid will have an impact on school funds.”

Just days prior to most schools re-opening fully to pupils, the Minister announced a £42 million package of funding support for safe reopening but admits a financial “leap into the dark” on guessing the level of funding that will be required going forward.

“This is not something that will be solved overnight but it’s about narrowing that gap to reach a point where schools are on a more sustainable basis.”

Review

Turning to the promise by the Executive to establish an “external, independent review of education provision”, Weir says that following delays, he hopes work will commence in Autumn.

“Again, it’s not a couple of months job. If we’re going to look at this thoroughly then it needs to look at all aspects and that takes time. What I would say is that there is a need for ongoing change and reform of education and while I think a review will be significant in focussing in on that, these issues can’t wait until a report is produced. Where there are changes that can be made and that will be beneficial, I think they need to be made as soon as possible.”

As with a lot of the major reforms outlined in NDNA, there are concerns that the end of the Assembly mandate in 2022 could disrupt any long-term planning. Weir rejects the proposal that given the volume of work required, the findings of the review of education provision may never cross his desk.

“I think we would aim for a timeframe that certainly any report would have to be completed within this mandate,” he explains. “It’s about setting a long-term vision and establishing practical measures. It may well be, and it would be impossible and wrong of me to prejudge any outcome, that these will have taken place over a number of years. Other elements may be able to be implemented very quickly.”

Shared education and integration

A further ambition of NDNA was that the Executive will support educating children and young people of different backgrounds together in the classroom. Critics have pointed to a piecemeal approach to integration through education in the past, including a perceived shift in focus away from integrated education to a shared education model.

Weir, however, takes a more practical outlook: “I don’t think it’s one-size-fits-all. You could have a situation where it can mean different sectors coming together and, for example, amalgamating into a single school, which potentially could be integrated. But it could also mean shared education, where there has been a lot of good work to date, providing levels of practical, sustainable choices and improvements. For example, at GCSE and A-level it may not be cost effective or productive for a school to offer a particular subject but it might be that working with a number of other schools that they are able to share that out.

“Unfortunately, whilst there is still provision within the guidance for area learning, there is a recognition that under Covid, in the short term that will be something that is more difficult to achieve. There is an irony in that while there is rightly a desire to see as much sharing and mixing as possible between pupils, the Covid situation is seeing them being more ring-fenced than ever, which is unfortunate.”

Quizzed on whether shared education was serving as a barrier to expansion of integrated education in Northern Ireland, Weir says: “I don’t view particular sectors in a pejorative way so, there has got to be room that if someone wishes to send their children to a maintained school, a controlled school or an Irish medium school, that it is an equally valid choice as the integrated school.

“Education has a knock-on effect from other issues and the school estate will reflect the demographics of Northern Ireland. I think from that point of view, if we are looking at getting the maximum level of mixing of our pupils across society as a whole, that it’s important we produce genuine levels of mixing, rather than simply badging something for the sake of badging it.”

Underachievement

In July, the Minister announced the appointment of an expert panel to examine the links between educational underachievement and social disadvantage, another pledge of NDNA, which he says reflects a considerable wealth of experience on the issue. Outlining that the panel will take onboard extensive research already done around the issue and learnings from across the globe, he is adamant that any recommendations must be implementable. “It’s got to be grounded in something that is doable,” he says.

The impacts of social economic background on educational outcome is often a topic which gains more attention in late summer and early autumn, with the issuing of exam results. Potentially this year, more than any other year, it received widespread attention after the decision not to hold exams in favour of the use of an algorithm in the grading of A-levels to standardise results. The method was later scrapped in favour of teacher predicted grades, following complaints that the use of the algorithm disadvantaged those in lower performing schools. In the end, the Minister was forced to announce that pupils would be awarded the highest grade either predicted by their teacher or awarded officially via the algorithm.

Schools are entitled to use academic selection as a means to select their pupils and I suppose, if it’s being used, the best and realistic way of judging that is some form of test.

The recognised impact of social-economic background on exam outcomes, even prior to this year’s results fiasco, have been long-standing and has led to calls for reform in how pupils are assessed away from the test scenario. However, Weir believes that 2020 has only served to highlight that examinations remain the fairest method in delivering objective results.

“One of the interesting things around Northern Ireland’s attainment gap is that in recent years we’ve seen steadily rising exam performance and, importantly, the gap has been closing. This year, even under the two different methods, schools improved across the board and the performance of non-selective schools was improving at a faster rate.”

Asked whether a review of this year’s process may lead to a wider review of the assessment system, Weir outlines: “I think one of the lessons which emerged was that the best possible way of assessing people is by way of examinations. With examinations people have a sense of being treated fairly and at least, from the point of view of results, while they can be disappointed, objectively they can have no complaints.”

Quizzed on whether his outlook held true for the transfer test, Weir adds: “Schools are entitled to use academic selection as a means to select their pupils and I suppose, if it’s being used, the best and realistic way of judging that is some form of test.” The Minister puts the onus on those favouring the end of the tests to devise a fairer system and adds that all too often discussions on under performance and the attainment gap are focussed on selection.

“The vast bulk of educational experts will say that if you are looking to make interventions that will benefit children’s lives then you need to do it at the earliest opportunity, which is probably before they go through the school doors. The arguments over selection to some extent distract from the real change that needs to take place. The Department has had a considerable focus on early interventions and some of that is producing dividends.”

On whether he holds any regrets about this year’s results outcome, Weir outlines a difficult situation where he believes any system, in the absence of examinations, was going to be unfair for some and increase fairness for others.

“Ultimately, there has been a very strong lesson that everything beyond examination will be sub-optimal in its nature. I’m sorry for, at times, a lot of the stress that people were put under. To some extent that will happen every year with examinations, but I think the fact that we were in to such a mix of unparalleled situations, exacerbated that level of uncertainty.”

Assessment

Weir is reluctant to offer an appraisal of himself and his achievements since re-taking up the post since January , preferring, he says, to leave that to others, but offers: “I think the fact that we’ve made a start on things like the underachievement expert panel is significant. However, undoubtedly so much has been focussed in on trying to ensure that the system copes with Covid it has meant a lot of things have been delayed.”

On what he would like to achieve, the Minister adds: “There are a range of areas we need to see progress. We need reform, we need to see changes in terms of special education needs and we need to start the process of how we can better help our pupils in those pockets of underachievement.

“We are working to make our schools more sustainable and ensure that we have an education system that is structurally more fit for purpose. I think between ourselves and the Department for the Economy, beginning to drive a digital skills agenda will be critical.

“There has got to be a realisation that the world that was there is not the world today. Education is both an end and a means to an end and it’s about preparing our young people for as successful lives as they can obtain. We need to make sure there are no barriers to an individual obtaining the most in life.”