Education under attainment underpins poor economic growth

Northern Ireland’s inability to match the levels of educational attainment of its population to the needs of the modern economy is a major factor in its poor economic growth, argues economist John FitzGerald.

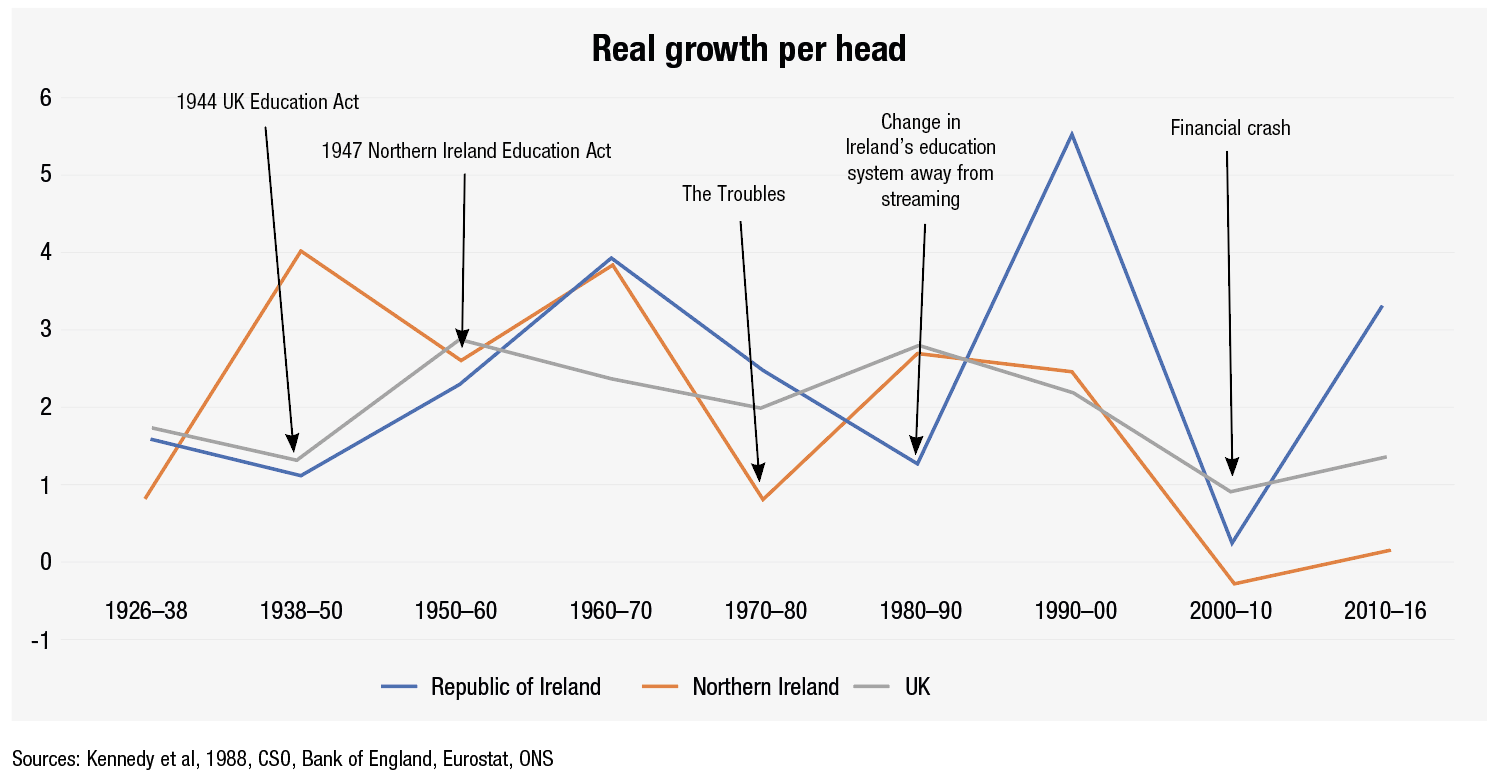

Since 1990, real growth per head in Northern Ireland has remained low when compared to the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Currently, the annual rate of growth in Northern Ireland (0.8 per cent) is around half of the rate in the UK (1.5 per cent) and less than three times the rate in the Republic of Ireland (3 per cent).

The ESRI’s John Fitzgerald believes that poor economic performance can be related directly to underinvestment in education and selection of pupils within the system.

“A failure to invest effectively in education is crucial in Northern Ireland’s poor economic performance within a UK context,” he says, adding: “The selective nature of the educational system does serious damage to the economy and society and the challenge will be how best to rapidly evolve to a more inclusive system.”

Underlining the link between education investment and economic output FitzGerald highlights labour market data from the EU15 which shows a low elasticity of substitution between skilled and unskilled labour. “It’s recognisable that a failure to match labour supply and demand leads to unemployment,” he explains.

Statistics over the last 15 years highlight that, even during recession years, the employment of graduates has continued to grow and the unemployment gap remains small. This is in contrast to figures for those who did not complete secondary school for the same period.

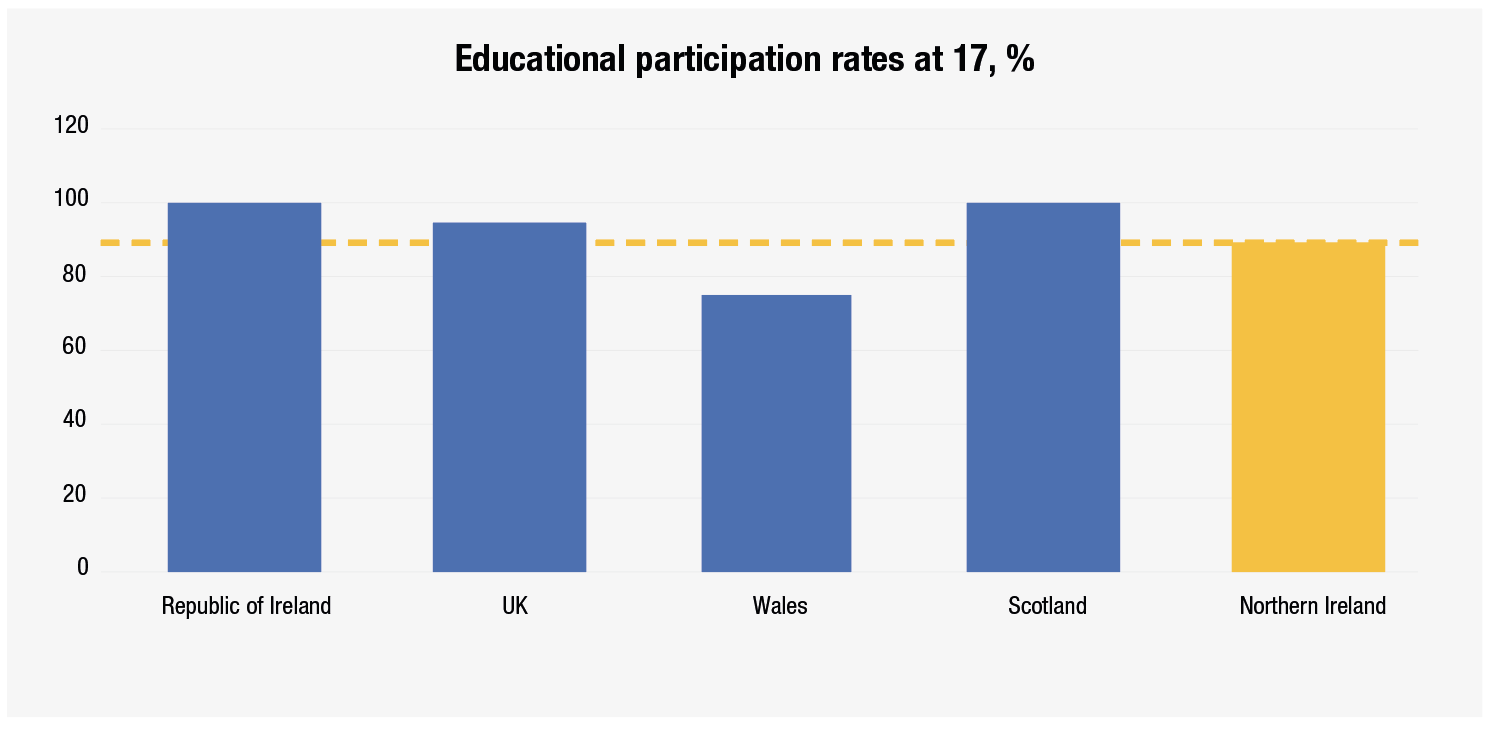

Northern Ireland currently has the second lowest participation rates at 17 across the UK and Ireland, second only behind Wales and the model of grammar and secondary schools has changed little from the model established under the 1947 Northern Ireland Education Act. In contrast, England modified its model in the 1960s and in the 1980s, the Republic of Ireland changed its policies on the back of research which highlighted the negative impact streaming was having on less talented pupils.

Research carried out by Borooah in 2015 highlights the serious disadvantage being placed on the remaining 60 per cent of pupils in Northern Ireland when 40 per cent were selected in to grammar schools.

Also included in the findings was that taken collectively, Northern Ireland’s post-primary secondary schools failed to meet the minimum acceptable standard for post-primary schools in England and that only 20 per cent of Protestant boys from a deprived background reached the requisite standard, compared to 33 per cent of Catholic boys from the same background.

The impact of the differing policies on education attainment in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland can be mapped in the context of wider European performance. For those born in the early 1930s both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland ranked low and behind the EU15 and EU27 averages for secondary school completions. However, by the early 1980s the Republic of Ireland had moved dramatically up the rankings, well above the EU15 and EU27 averages, while Northern Ireland, though still increasing their rate, had moved little by comparison.

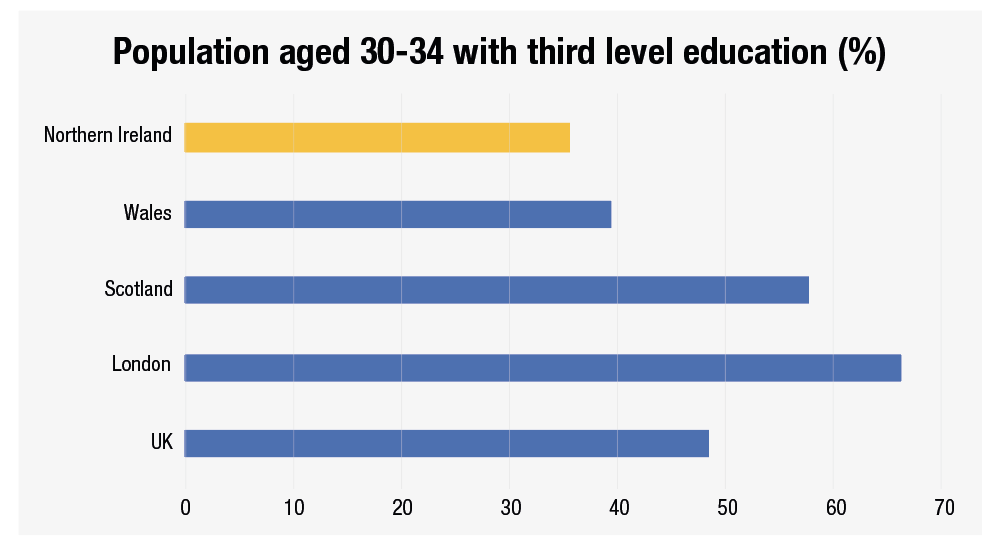

The outworkings of differing education policies is evident in a recent analysis of educational attainment levels for those aged 30-34 done in 2017. Across the UK regions and Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland has the highest proportion of early school leavers and the lowest proportion of graduates within this age bracket. In comparison, Ireland has the lowest proportion of early school leavers and highest proportion of graduates. Outside of London, Scotland is the closest performer to Ireland in this regard.

FitzGerald says: “Scotland’s performance is no accident. The Scottish system of education involves mixed ability teaching and Government policy has given greater attention to education than much of the rest of the UK.”

FitzGerald believes that Northern Ireland’s economic problem is compounded further by the fact that almost 25 per cent of its graduates are living in England and Wales, compared to just of 8 per cent of Irish graduates doing the same.

“Northern Ireland is not producing enough graduates and, of those that there are, a large number go to the UK,” explains FitzGerald.

In 2017, 19 per cent of Northern Ireland’s first year students were in third level institutions in Great Britain and statistics suggest that two thirds of those studying in England or Scotland do not return to work in Northern Ireland.

FitzGerald says that these figures are evidence that Northern Ireland is “losing at both ends of the educational system”. Explaining this further, he says that human capital affects the economy through three key channels: productivity; labour force participation; and the reduced probability of unemployment.

Highlighting a range of studies done in Ireland which all point to a major contribution to Ireland’s economy over the past 20-30 years being the upgrading of human capital, he points to one in particular by Breen and Shortall, 1992, which showed that keeping children in school so they completed the Junior Cert, exam, not only reduced the likelihood of unemployability, but also brought about savings to the State in reduced unemployment benefit.

FitzGerald also points to his own research paper looking at the contribution of rising educational attainment to growth between 1992-2010 which estimated that 2.5 percentage points of the annual growth in the Republic of Ireland can be attributed to the upgrading of the educational attainment of the population.

A similar study focussed on Northern Ireland by Borooah estimates that upgrading education would bring about better returns for the individual and add 0.25 percentage points to productivity growth.

A 2019 study by FitzGerald estimated that if Northern Ireland was to adopt the Scottish education system, it would add 1 per cent a year to growth and another 2019 study by Siedschlag and Koecklin pointed to a significant impact of education on foreign direct Investment (FDI).

FitzGerald says: “In the Republic of Ireland investment in education has played a crucial role in growth. Inclusive education is a vital tenet of this and that does not simply mean third level education. Much of the success in recent years can be attributed to a policy focus on reducing early school leaving and that change in perception that education was important and plays a big role in growth rates.”

The academic believes that reform of the education system in Northern Ireland today would take some 20 to 30 years to impact on the economic performance. However, he believes there is an existing quick win measure that could take earlier effect. He suggests that Northern Ireland should make itself attractive to those young people who have emigrated, highlighting that a factor in Ireland’s success is that while over one third of all graduates leave Ireland, a large number also return, unlike Northern Ireland.

ESRI research suggests that those who return to the Republic of Ireland earn 10 per cent more and increase their productivity by 10 per cent as a result of their learnings abroad.

“Attracting back a large number of graduates could have a major economic impact,” he says.

FitzGerald also believes that Northern Ireland needs to transform its investment in education to sustain real growth, however, he also recognises potential challenges to such a policy switch. Recognising the rise of English nationalism which is culminating in the form of Brexit, he says: “Northern Ireland faces huge economic problems which will be aggravated by Brexit, however, economic problems alone are not the only challenge.

“Northern Ireland depends for over 20 per cent of its income on transfers from London. The rise of English nationalism may threaten the long-term future of those transfers. To that end, Northern Ireland must transition to a more productive economy, relying more on its own resources and less on transfers from London.

“Education is the sector in which I would begin this transition,” he concludes.