Eamonn McCann: Civil rights legacy marches on

In spite of a banning order, the first civil rights march in Derry took place on 5 October 1968, resulting in marchers being beaten off the streets by the RUC. Reflecting on the 50th anniversary, Ciarán Galway meets the indefatigable Eamonn McCann, then a leading civil rights activist, to contextualise the movement and explore its subsequent legacy.

“It is true that Derry is unique,” asserts McCann, adding: “I don’t say that out of parochial patriotism, but many of the things which happened in Derry can be explained by geography, by demography, by tradition and the border.

“The biggest concentration of Catholics in Northern Ireland was on the west bank of the Foyle in Derry – bigger than any particular area in Belfast. So, at one and the same time, because they were a majority, they felt the sting of discrimination and particularly of elections more so than anywhere else.

“They were also quite self-confident in being a big majority. There was never a sense of siege that was felt in Short Strand, Ardoyne, the New Lodge and lots of places in Belfast. That’s one of the reasons why the civil rights movement sparked into a mass movement in Derry.”

On top of this, the geography of Derry means that for most people living on the cityside, the Donegal border is within three miles to the north, south or west. Indeed, the west bank of the River Foyle historically constituted a portion of Donegal.

Consequently, McCann contends that this instilled Derry’s Catholics with a self-confidence, and, while attempts may be made to define a broad ‘nationalist tradition’ in Northern Ireland, there is a heterogeneity which hinges on geography.

“That’s the combination of the stuff which, in the 1960s, gave rise to the civil rights movement in Derry,” explains McCann. “It’s also, incidentally, the reason why the shooting war, in effect, ended in Derry after 1989. Five years before the first IRA ceasefire, it was over in Derry.” This is a reference to the local revulsion that marked the final killings of British soldiers and RUC personnel by the IRA in Derry (in 1990 and 1993 respectively).

Personal context

Unsurprisingly, McCann comes from a staunch socialist and trade union background. His father, Ned McCann, was a member of Derry Trade Union Council for many years – footsteps in which his son has followed.

“At the start, I would have regarded myself as a socialist before I knew the meaning of the word. Some of my earliest memories are about our front room, which like many front rooms in two-up-two-down houses was amazingly unused, was when groups of men – always men – were having a trade union meeting. That gave me a wee bit of a grounding in it.

“Then there was the talk around the house. My father saw James Connolly speaking on the corner of New Lodge Road and Lepper Street [in Belfast]. All of those stories were legendary in our house,” he discloses.

McCann’s father was “very anti-Tory” and possessed “a curious combination of being a devout Catholic and also a devout socialist”. Primarily referred to as ‘Ned McCann the labour man’, the erstwhile People Before Profit MLA states: “My father’s proudest boast – and we came from Rossville Street in the heart of the Bogside – was that there never was a nationalist vote went out of [our] house… I came out of that milieu.”

Internationalism

The ‘60s were a period of tectonic change in which “there was no shortage of causes to associate yourself with”. As was the case almost everywhere else, McCann emphasises the significance of particular events in 1967 and 1968 for young people in Ireland.

For instance, January 1968 marked the beginning of the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, Martin Luther King was assassinated in April 1968, the Student Uprising ignited in France, Bobby Kennedy was killed in June 1968, the anti-Vietnam War movement and the Black Panthers emerged on American streets and universities were occupied.

“There was a sense of excitement, a sense of a cultural turning point, a sense of a new generation taking over and a sense, not just of rebellion, but defiance of the established order,” he describes.

“There was that sort of hubbub of things which, on the face of it, had very little to do with what was happening in Northern Ireland. We had only got the intercommunity rivalry or hostility – or at least that was the conventional wisdom,” he comments wryly.

“It is not without significance that the people who organised the first civil rights march in Derry in October were not nationalists. Not one of us would have called ourselves nationalists. Not one of us. A couple of people, such as Johnnie White, would have been republicans, but certainly not of the Provo stamp.”

“There was a sense of excitement, a sense of a cultural turning point, a sense of a new generation taking over and a sense, not just of rebellion, but defiance of the established order.”

However, McCann feels that the internationalism of the civil rights movement is often neglected. “You can read books about Northern Ireland in which the international dimension of the early civil rights isn’t mentioned at all, as if it never happened. The reason for that is quite simple – it doesn’t suit any major group in Ireland, north or south, to see it or remember it like that. So, they don’t. Everything is being crammed all the time into a neat dichotomy.”

Rationale

Simultaneously, in Derry, as was the case elsewhere, housing and employment were major grievances. When McCann and others founded the Derry Housing Action Committee in the spring of 1968, it immediately took root. “People could see that ‘we might win this’ and came out onto the street. The civil rights movement was very broad. It started first in Derry and was very open. If you were to ask me who were the members, I’d have no idea. When it began, it was people from the Housing Action Committee and an Unemployed Action Committee, which never really got off the ground to the same extent.”

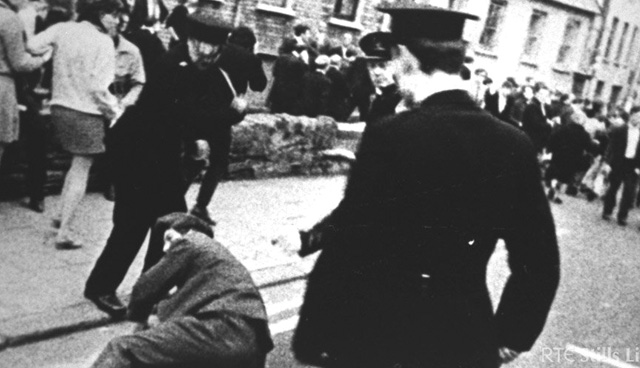

Following the first civil rights March from Coalisland to Dungannon in August 1968, the Derry Housing Action Committee requested that the second march be held in Derry, which was subsequently banned by then Northern Ireland Home Affairs Minister, William Craig. In the event, marchers were baton-charged by the RUC and the footage captured by RTÉ.

“There was an element of provocation, deliberate provocation on our part, in that it never occurred to us to obey the banning order,” McCann acknowledges. “I remember getting the banning order on the Friday before the march at four in the morning. Two cops at the door handed in this little piece of paper telling us the march was banned. I remember that as soon as we got it, we thought it added another dimension to what we were doing, but it never really occurred to me to obey it.

“The RUC can claim an awful lot of credit for the civil rights movement. If they had not behaved like lunatics on 5 October, I’m not sure what would have emerged from it. I think Northern Ireland society was heading for a crisis anyway, but… There certainly wouldn’t have been the mass movement sparked if it had not been for 5 October.”

Achievements

On the whole, the veteran activist regards the civil rights movement as having been successful in terms of what it achieved in its programme. The establishment of the Northern Ireland Housing Executive, the abolition of unfair electoral boundaries, the abolition of the business vote, the abolition of the B Specials, the abolition of the Special Powers Act (which never quite took) and laws against job discrimination were, he maintains, won through ‘people power’.

“Some of them were just promises, but those things which were delivered by the civil rights movement; were delivered by the mass mobilisation of tens of thousands of people. They were not delivered by parliamentary action at Stormont or anywhere else and they most certainly were not delivered by the IRA’s armed struggle, which has delivered fuck all.

“If you look back and ask: ‘What worked? What was successful? What went some way to achieving its goals?’ The civil rights movement is a better example. It was by no means perfect, but I do think it emerges with great credit from the history of the last 50 years and it is arguably the most successful movement that there has been in the North, certainly since the coming of the women’s movement.”

Regrets

However, McCann rues the movement’s inability to provide a mass alternative to sectarian politics as a failure. “I think it was a very significant success which didn’t last. That’s the way I look at it. It absolutely failed to create a new politics in Northern Ireland,” he laments.

“Anybody who looks back on 50 years and says, ‘I never made a mistake’, is a liar or a fool. We all make mistakes. Huge mistakes were made in the 1960s in the course of the broad civil rights movement. But I think the civil rights movement achieved an awful lot.”

Personally, McCann has “loads of regrets”. The spirit of the age, particularly among young people was spontaneity. “That suited if you were of that age or that mind and you were excited. It was working, that’s the thing. We had all these gains and the Government was on the run, so why change?

“But, when the smoke had cleared, there was no organisation. They hadn’t built an organisation. The civil rights movement was very broad and fragile. Unstable in its ideology and its practices. It really wasn’t up to the job of taking on these orange and green boxes in the North.”

The responsibility for this failure, and the subsequent course of events, he argues, lies with those who were around at the time and involved. “The pattern that was imposed upon events was one which divided the people into ‘the two communities’ no matter what you did about it. We didn’t take that seriously enough – we vastly underestimated the strength of nationalism and the stupidity of unionism and the violent nature of the State.

“I think it has to be said that, sadly, on the face of it, the left had a lot of influence in the early days of the civil rights movement. We frittered it away. No question of that. We frittered it away. We have to learn lessons from that and look back.”

Ownership

Today, the legacy of the civil rights movement is a contested historical space with several groups and individuals vying for ownership. “The way the civil rights movement emerged in Derry, loads of people can look back and make a legitimate claim on it,” suggests McCann, before adding: “Now, of course, I would think they’re all wrong.

“The only people who can [legitimately] lay claim to it are the people there at the time – the SDLP, the Stickies and the Communist Party to an extent. There were no unionist parties involved and, of course, [Provisional] Sinn Féin hadn’t been formed so it wasn’t involved in any shape, form or fashion – which it has to be reminded of now and again. They keep writing articles claiming that they are the legitimate inheritors of the tradition – no they’re fucking not,” he elaborates.

At the same time, McCann emphasises the distinction of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association as a different animal from the civil rights movement. “The Civil Rights Association was part of it, but by no means all of it and there was a semi-spontaneous element,” he stresses.

With regards to Sinn Féin’s claim to the movement, McCann contends: “The ideas which animated the civil rights movement had got nothing to do with Sinn Féin or the Provos. They certainly didn’t have anything to do with armed struggle or ‘the fourth green field’ and all that. That was not part of the agenda.

“There is all this mish mash going on and nobody owns the legacy of the civil rights movement. People can make a bid for it, but because nobody owns the legacy of it, hardly anybody wants to remember the way it was. We all remember it differently.”

“Nobody owns the legacy of the civil rights movement. People can make a bid for it, but because nobody owns the legacy of it, hardly anybody wants to remember the way it was. We all remember it differently.”

Through a prominent column, former DUP MLA, Nelson McCausland frequently reminds his readers of one such alternative interpretation of the civil rights movement, describing it as “republican socialist strategy to undermine Northern Ireland”.

“Of course [McCausland] is right that we wanted to destabilise Northern Ireland. We wanted to destabilise southern Ireland. We wanted to destabilise Britain and America. After all, the idea was that another world is possible. I remember speaking to thousands of people in Paris in 1968 along with Bernadette McAliskey and we were all one together.

“It wasn’t crazy, at that time, to see what we were doing in Northern Ireland as part of something huge that was happening all over the world. So, when you look back on it and think, ‘that was all just fluff and vapour’ – it wasn’t. Real efforts were put in to achieve that. I still believe absolutely that that was the right approach. We weren’t capable of implementing it, but that was largely our own fault,” McCann remarks.

Reverberation

The Bogside native believes that the basic tenet of the civil rights movement – ‘people power’ – absolutely resonates today. “Thousands and thousands of people on the streets is what delivered the reforms of the late 60s and early 70s – it wasn’t parliament or the Government, it was people power. That’s the only thing that has actually pushed things forward and it’s still the case today.

“Does anyone believe that there would have been the law for equal marriage if people had not been on the streets in their thousands? Does anyone believe that we would have got rid of the Eighth Amendment from the Constitution or water charges? None of those things were won in parliament or by somebody holding up a gun – they were won by masses of people. Nothing else is going to work.”

As such, McCann is absolutely convinced that the only way partition is ever going to be ended is in the course of mass upsurges in both states. This, he notes, was exemplified by the protests which followed the rugby rape trial in Belfast. “You had people out in Cork, Limerick, Galway and Dublin without any real organisation – it was spontaneous. There was a united Ireland in operation and in practice. Those were demonstrations not for a united Ireland, but of a united Ireland.

“What was missing from the women’s demonstrations was somebody saying, ‘this is a united Ireland, this is what we mean. We mean a society all over Ireland’. The only way you have any right to expect people from the unionist tradition in the North to opt for a united Ireland is if they believe that they are going to be comfortable in it and that things are going to be better than they are now. You can’t say, ‘take a chance’ – that’s not going to fucking happen.”