Deficits and cuts

With the announcement of public spending cuts, Owen McQuade looks at the UK deficit and how any changes made by George Osborne and his team might impact on Northern Ireland.

With the announcement of public spending cuts, Owen McQuade looks at the UK deficit and how any changes made by George Osborne and his team might impact on Northern Ireland.

Perhaps the main reason why David Cameron and his Conservative colleagues opted for a formal coalition, the first for 65 years, was that they realised the cutting of public spending in the parliament ahead would be politically very treacherous.

As the new administration prepares for its first budget, the deficit stands at £156 billion at the end of the last financial year 2009-2010. At 11.6 per cent of national income this was by far the biggest deficit since the Second World War.

George Osborne on 24 May announced spending cuts of £6.2 billion in the current financial year 2010-2011. These immediate cuts will be followed by a more severe three-year spending review in the autumn. In the budget on 22 June he will lay out plans to eliminate most of the structural budget before the next election, which is set for 2015.

Office for Budget Responsibility

On taking office, Osborne made a move, similar to when Brown took office and gave the Bank of England the responsibility for setting interest rates, to hand over power to a new Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). This new office will provide the economic and fiscal forecasts on which budgets are based.

When Gordon Brown was chancellor he made much of fiscal rules regarding deficits and the level of debt. But with the economic crisis these were set to one side. Key parameters that can make future finances healthier than they really are, are the forecast figures as future GDP growth.

OBR’s power will come from the authority’s committee chaired by Sir Alan Budd, a founder member of the monetary policy committee. The June budget will be preceded by a crucial report from OBR which will detail independent economic and fiscal forecasts that will form the basis of the budget calculations. The office is expected to paint a much darker picture than the fiscal projections in Labour’s last budget in March, which forecast GDP growth to reach 3 per cent in 2011.

This intervention could pave the way for tax rises including perhaps a rise in VAT. Although tax rises will prove unpopular with the public, cuts in public spending will prove more difficult to deliver. Although much of the focus is on public sector spending, nearly one-third of the total spending is on the welfare budget; cuts in welfare may well test the strength of the Conservative Lib Dem coalition.

Right up there

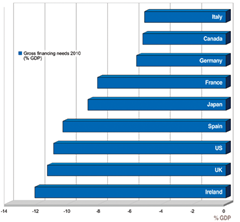

Whilst much has been made of the economic woes south of the border, unlike the Republic the UK has not yet addressed the need to reduce the deficit and reduce spending and perhaps raise taxes. The UK’s deficit is of a similar magnitude to Ireland and Spain and is the largest of the G7 countries. However, unlike the rest of Europe the UK is able to let its currency devalue which will help export-led growth.

Do deficits matter?

A year ago we were all Keynesians, with the conventional wisdom that government spending should fuel a failing economy. In the Republic, because the deficit and the amount of debt were higher than most other European countries, the Government took drastic action in an emergency budget. In contrast the UK did not cut its spending. One year on both the size of Ireland’s deficit and the amount of debt are nearly the same as the UK’s and yet the mindset of the Irish public and policy-makers is one of working through a crisis and preparing for the next wave of pain. In the UK there is no sense of crisis, yet.

There has been much debate about whether deficits matter or not. With the new UK coalition government moving to make cuts there has been some reaction from commentators and politicians that such cuts might damage any recovery. The counter-argument is that we are two years into the downturn and the cutting of the deficit should start now. There is a similar debate in the US with Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman talking of any cuts in spending leading to a ‘lost decade’ similar to Japan, with high unemployment and low growth.

Budget cuts

Although only 1 per cent of the £620 billion annual public sector spend, the £6.2 billion cuts are the first in what is expected to be deeper cuts in the autumn. This first wave of cuts was identified by the new coalition within one week of taking office and represents “low-lying fruit”, which includes a freeze on civil service recruitment and a reduction in spending in areas such as IT and consultancy services. It also includes stopping some projects and reducing the size of some nongovernmental public bodies.

Although only 1 per cent of the £620 billion annual public sector spend, the £6.2 billion cuts are the first in what is expected to be deeper cuts in the autumn. This first wave of cuts was identified by the new coalition within one week of taking office and represents “low-lying fruit”, which includes a freeze on civil service recruitment and a reduction in spending in areas such as IT and consultancy services. It also includes stopping some projects and reducing the size of some nongovernmental public bodies.

The newly formed Cabinet has set an example, with ministers’ salaries cut by 5 per cent. The Lib Dems had previously opposed making cuts this year, arguing that such a move could negatively impact on any recovery. But the Lib Dem Chief Secretary at the Treasury, David Laws, said that the eurozone debt crisis had persuaded him to change his mind.

George Osborne has stated that he wants to eliminate the structural deficit within the five-year term of the parliament, which could equate to cuts of 20 per cent or more. Such deep cuts would test the newly formed coalition government.

As part of the expenditure cuts, Northern Ireland will face cuts of around £128 million. Like the other devolved administrations, the Executive has the option of delaying budget cuts until next year. Scotland has chosen to defer such cuts, with Northern Ireland and Wales still to decide.