Critical care capacity

The number of critical care beds available in Northern Ireland on any one day has changed little in the last year despite the pandemic, writes David Whelan.

While Northern Ireland’s surge planning has facilitated the potential for additional critical care beds, the permanent capacity of critical care across the health service remains at around half that of the European average.

Surge plans published by the Department of Health identified a potential increase in critical care capacity to 286 critical care beds across Northern Ireland as the impacts of Covid-19 began to be felt. However, in early December 2020, the Health and Social Care Board (HSCB) confirmed that the number of critical care beds commissioned (the number routinely available on any given day) remained largely the same as 2019, despite the onset of the pandemic.

The HSCB commissions beds across nine intensive care units in Northern Ireland and collates availability through daily updates. Capacity figures change depending on demand and staffing but since mid-October 2020, these have generally ranged from between 80 to 120.

Unlike the Republic of Ireland, for example, where the Department of Health has set about simultaneously increasing permanent critical care capacity and ensuring surge capacity as required, evidence suggests that little change has been made to permanent capacity in Northern Ireland.

The impact of this is two-fold. Firstly, Northern Ireland’s health system is unlikely to benefit from any increased critical care capacity post-Covid and secondly, any deployment of surge capacity will require a significant redeployment of staff, at a time when he system is already under significant pressure.

In March 2020, the Department of Health Permanent Secretary Richard Pengelly wrote to the Chief Executives of all arm’s length bodies warning that “the availability of our most valuable resources needed to counter Covid-19 – beds, our staff and equipment – will all come under increasing pressure”.

Pengelly was outlining surge planning as the virus continued to spread across Northern Ireland but the context for the warning was a health service already at breaking point with the longest waiting lists for elective care in Europe, a staffing crisis which had just months previously provoked frontline nurses to strike, highlighting the previous absence of any political direction for over three years.

In the weeks and months that followed, resources were directed to manage Covid-19 demand, causing significant disruption to many areas of elective care and inevitably, placed further pressures on health and care services.

In October 2020, the Department of Health’s Surge Planning Framework somewhat acknowledged this when it highlighted that HSC Trusts have routinely been close to, or exceeded, their available capacity in recent winters. It added that that the reconfiguration of services during the first wave of Covid-19 will likely “reduce the existing capacity of the system to deal with large numbers of patients”.

The reality of this was apparent in mid-December 2020 when in one night between 30 to 35 ambulances queued outside full emergency departments across Northern Ireland. In one instance, 17 people were treated in the ambulances in the carpark of Antrim Area Hospital while 43 people waited to be admitted inside.

Acute service planning in Northern Ireland focused on the rapid expansion of critical care and acute bed capacity. The Critical Care Network for Northern Ireland (CCaNNI) was tasked with rapidly developing a regional critical care surge plan and, in parallel, the Belfast City Hospital was designated as Northern Ireland’s first Nightingale hospital providing an additional 75 critical care beds. The CCaNNI surge plan allowed for a total capacity of 286 critical care beds. However, the number of general adult critical care beds operational at any point in time has generally been in the range of 80-120 since mid-October, according to the HSCB.

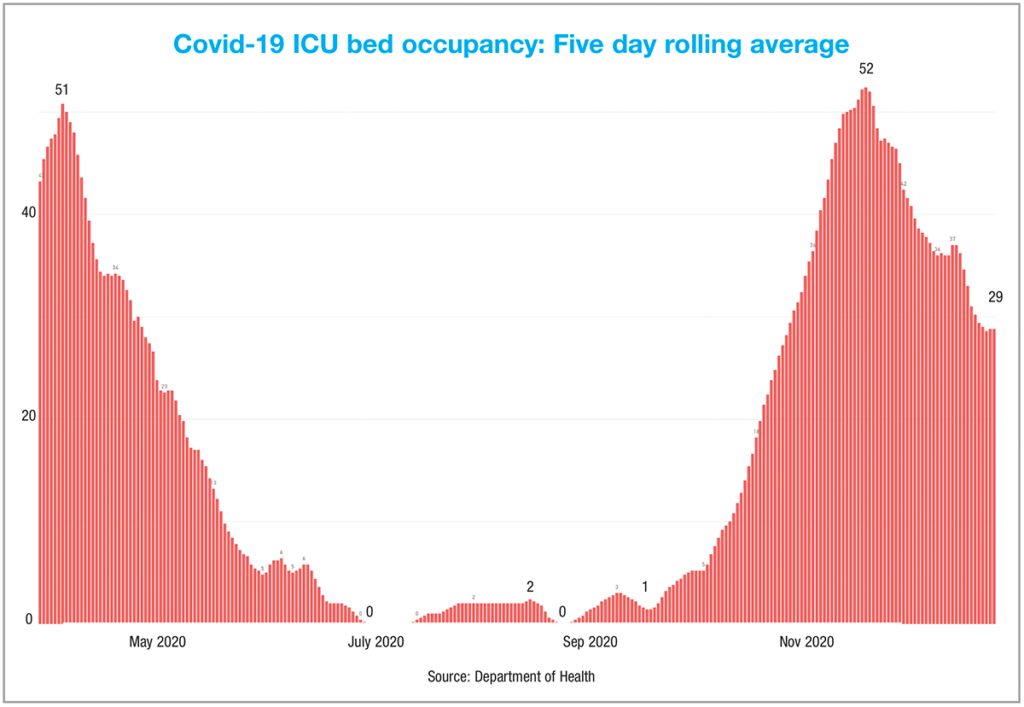

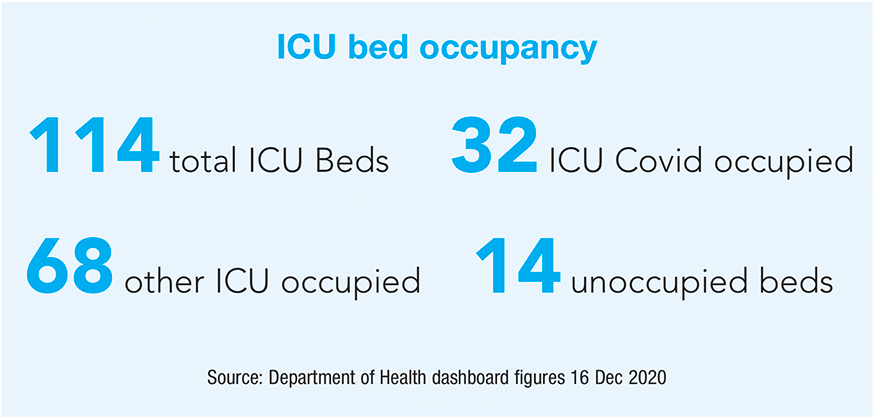

In October, now acknowledged as the beginning of Northern Ireland’s second wave of Covid-19, alarm was raised at reports that Intensive Care Unit (ICU) capacity had exceeded 90 per cent.

The reports were based on public-facing statistics, published for the first time through the Department’s Covid-19 dashboard (which included paediatric and cardiac surgical ICU beds) but significantly, offered little pre-Covid context for ICU capacity levels in Northern Ireland’s failing health system and worked off figures of the number of commissioned critical care beds of any given day and not the total capacity outlined in the surge planning.

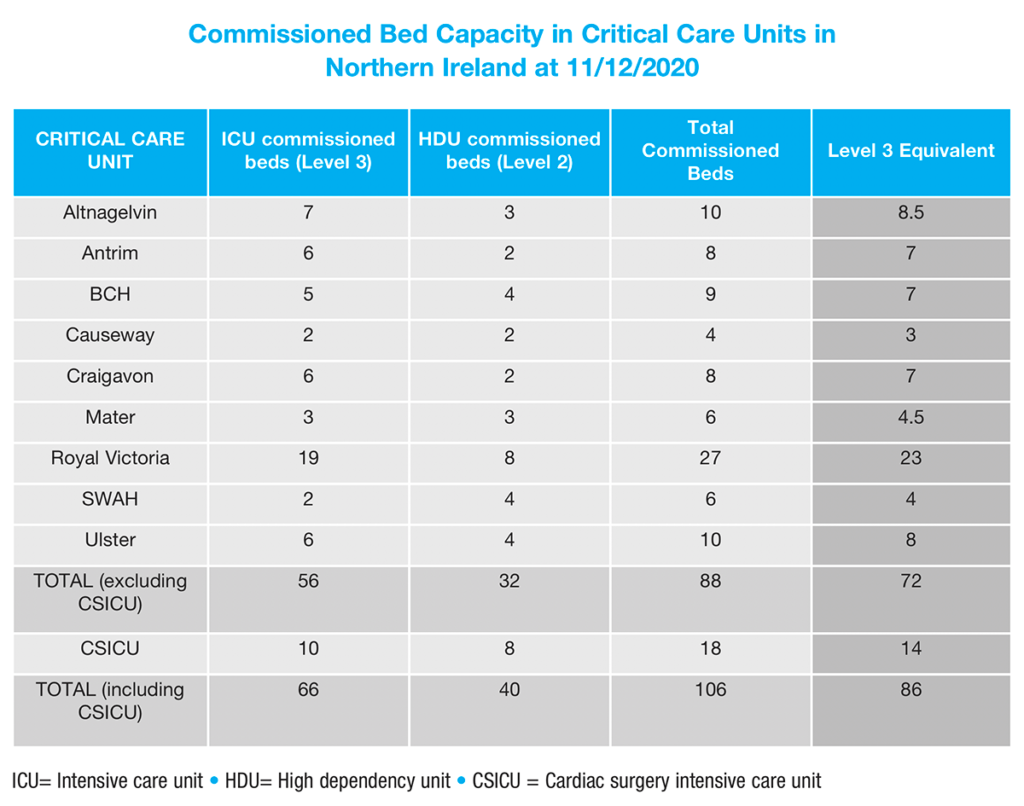

Bed availability is just one factor of informing ICU capacity. An equally important element is staffing capacity to manage ICU beds. Critical care unit capacity across Northern Ireland is defined in two ways: level two (high dependency) and level three (intensive care).

Levels of care provided to adult patients is classified by the Intensive Care Society into four levels of care. Level two patients require more detailed observation or intervention with support of a single organ system, while level three patients require advanced respiratory support alone, or basic respiratory support together with support of at least two organ systems.

The nursing resource required to operate one level three bed is equivalent to that of two level two beds. The flexibility across these levels mean that the Health and Social Care Board refer to level three-equivalent beds.

Several trusts have multiple critical care units and the way in which the surge capacity target is met can vary across those units depending on case mix and staffing. Target capacity varies depending on demand but capacity is managed to keep the occupancy level below the maximum of 85 per cent recommended by the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine.

At the time of request in December 2020, the HSCB provided figures outlining that there were 88 commissioned general critical care beds, made up of 56 level three beds and 32 level two beds, representing a 72 level-three equivalent beds.

The HSCB were unable to provide comparative data to assess whether any changes have been made to ICU capacity in recent years, due to the fact that a daily situation report from each critical care unit to the CCaNNI only began in March 2020. Prior to this, a daily bed return to the UK Bed Bureau was completed by trusts and collated differently.

However, a spokesperson for the HSCB confirmed that no change had occurred to the number of commissioned beds from the same period last year.

For context, Northern Ireland has a similar ratio of critical care beds per 100,000 people to the Republic of Ireland of around 5.5. The European average is 11.5 critical care beds per 100,000 people.

In March, the Republic of Ireland’s Department of Health brought the base adult critical care bed numbers from 257 adult beds (197 Level three and 60 Level two) to 285 (239 Level three and 46 Level two), a figure which still remained 145 beds short of the HSE’s own recommendation of 430 beds by 2031 and 294 beds short of recommended target for 2020, originally projected in 2009.

Alongside its surge planning, Health Service Executive (HSE) CEO Paul Reid has indicated an ambition to increase

its critical care capacity to 302 beds by January 2021.

However, it appears that little has been done in Northern Ireland, outside of surge planning, to increase the adult critical care capacity in the same way.

The HSCB says that alongside trusts, the CCANNI, historically, have ‘Regional Escalation Plans For Adult Critical Care’ in place, “to support the expansion of critical care capacity beyond commissioned baseline capacity, in proportional response to any increase in demand”.

“These escalation plans are in place at local and regional level and are to ensure plans are in place to manage increased demand such as the annual flu season or if there was a major incident/or accident, although additional plans have been required for the management of Covid cases.”

It adds that, as part of “normal business” these regional plans are regularly reviewed, refined and updated “to ensure that the whole critical care system in Northern Ireland is always in a state of readiness for an indeterminate period of critical care expansion”.