Crises and the labour market

Rising labour market inactivity and a fall in real-term earnings have been noticeable features of the impact of successive economic crises across the UK. However, for Northern Ireland, the scale of the impact can be traced beyond current economic turbulence, argues senior economist at the Nevin Economic Research Institute, Lisa Wilson.

Like most economies across Europe, successive economic crises in the shape of the Covid-19 pandemic, followed by the cost-of-living crisis, have disrupted the norms of the labour market.

In Great Britain, economists have pinpointed recent notable changes in two aspects of the labour market in the form of rising economic inactivity; and a decrease in real-term earnings, in the context of rising inflation.

Northern Ireland’s rise of labour market inactivity and decline in real-term earnings has been more acute but Wilson believes that longer-term structural problems in the economy are at fault.

“Stagnation is the central issue of the Northern Ireland economy and, with it, the labour market,” she affirms.

Outlining that economic inactivity is a long-standing structural problem in the Northern Ireland economy, Wilson highlights that the drive for the increase in Northern Ireland has been different than in other parts of Great Britain.

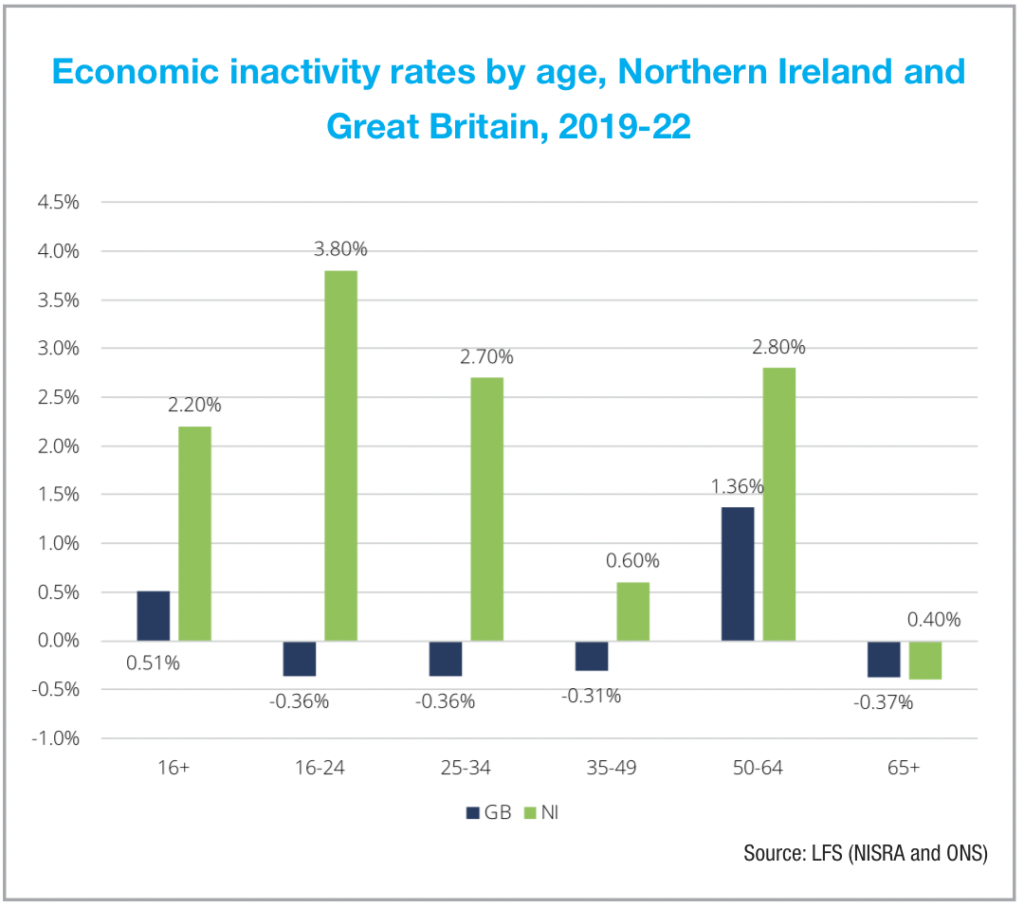

Research carried out by the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests that a rise in economic inactivity across Britain is being driven by older workers not returning to the workforce. In comparison, Northern Ireland’s rise has been across all age cohorts.

“While Great Britain may be experiencing a pandemic-induced increase in economic inactivity, it does not appear that the pandemic has been the principal driver of that trend in Northern Ireland. The movements in Northern Ireland would appear to be more connected with structural causes of economic inactivity which have been a feature of Northern Ireland’s labour market for many years,” explains Wilson.

“The long-term structural issue of economic inactivity is the most salient feature in the Northern Ireland economy,” she states. Emphasising the point, Wilson assesses inactivity over the past two decades, where there has been little change despite the introduction of numerous policies geared toward addressing the issue.

Earnings

Turning to earnings, Wilson believes that there is a general lack of awareness of other people’s earnings. Although this is not unique to Northern Ireland, it often comes as a surprise how low some people’s earnings are and how high some others’ earnings are. The hourly median pay for all workers in Northern Ireland is £13.39. Obvious disparities exist in the sub-data, for example, the hourly median rate for full-time workers (£14.79) is significantly higher than for part-time workers (£10.68) and overall males (£13.99) tend to earn more per hour than females (£12.82).

The distribution of earnings in Northern Ireland also tells a story. The lowest paid 10 per cent of workers in Northern Ireland earn an average of £9.51 per hour, compared to the best paid 10 per cent, who earn around £27 per hour. Both figures are significantly lower relative to the UK as a whole, or the Republic of Ireland.

2022 saw one of the sharpest declines in real earnings. Wilson explains that nominal wages in Northern Ireland saw the lowest growth of any region of the UK. However, median wage growth was higher than mean wage growth, implying that growth was stronger in the lower end of the distribution of wages or at least not concentrated at the top of the earnings distribution.

“What we have seen is that nominal earnings have increased on average by just under 6 per cent but the large spike of inflation has seen real earnings decline by just under 4 per cent. The result is that the average worker is earning 3.6 per cent less, on a weekly basis, this year compared to last.”

Wilson explains that the reality is likely to be a deeper decrease when considering that data collected in April 2022 is being compared to April 2021, when furlough was in place for some workers.

“We are comparing pay in a non-furlough year to a furlough year, which will be having a positive effect on measured pay growth as workers returned to work. This means that the actual squeeze on real pay underway in April 2022 is likely to be worse than what the data shows and this theory is supported by PAYE real-time data.”

Looking over the longer term, Wilson outlines that in five of the last 10 years, workers’ earnings have not kept pace with increases in the cost of living. “The notion that our earnings are not keeping pace with the cost of living is a new story is wrong. It is not new and has been going on for some time in the Northern Ireland labour market. Particularly from the 2008 financial crash, we have witnessed persistent and sustained periods of time where our earnings have not been keeping pace with the cost of living.”

Breaking this down further, Wilson says that an assessment of nominal and real wages over the past 20 years shows that public sector employees working full-time have seen no real pay progression in their earnings in 20 years. “We should expect more from an advanced economy,” she states, highlighting a £7 rise in median weekly earnings in the public sector since 2002.

Patterns in the private sector are somewhat different. While median weekly earnings in the private sector were £29 above 2002 levels in 2022, this figure masks the sustained increase in earnings which occurred up until the 2008 financial crash. Those increased levels have never been recovered.

Concluding, Wilson says: “The Northern Ireland labour market emerged from the Covid-19 crisis in a much healthier position than it did from the 2008 financial crisis. This was a significant achievement but also one that risks being undermined by the onset of a cost-of-living crisis.

“If the price level remains elevated and nominal earnings growth does not rise to close the gap, there is a significant danger of a dramatic contraction of consumption in the economy.

“The outworking of such a disruption for Northern Ireland’s labour market would likely bear a greater resemblance to the crisis of 2008 than to the crisis of 2020/21.”