Covid: The economic hangover

Economics editor of the Financial Times, Chris Giles, discusses the persistent economic scars set to be left by the pandemic and highlights the likelihood of increased taxes or decreased public spending to manage these.

Suggesting that the Covid-19 pandemic will leave lasting hangovers on the UK economy, Giles explains that the scale of the impact will be determined by the pace of recovery.

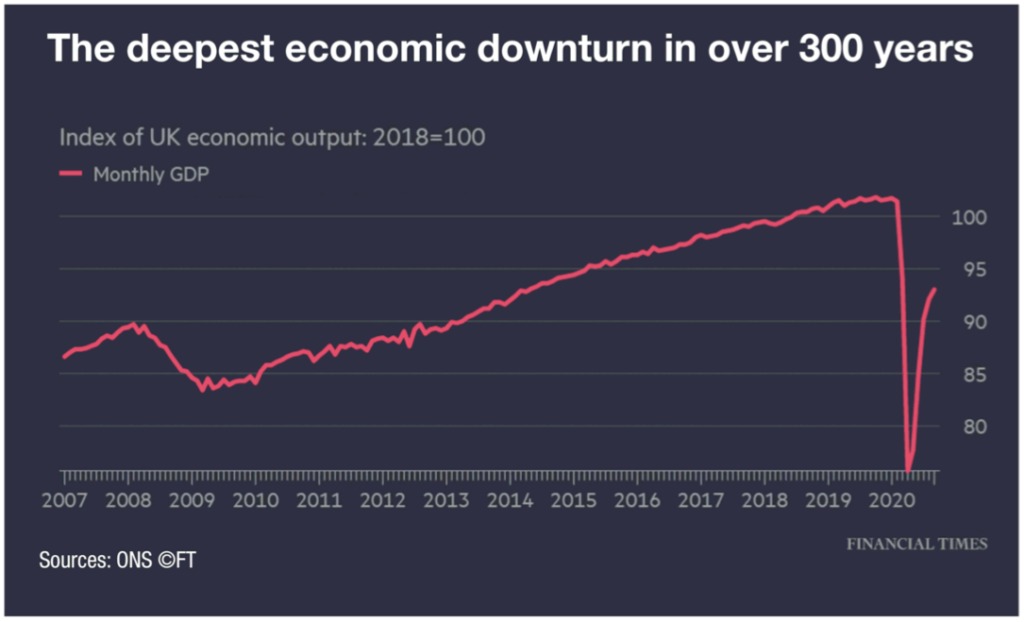

The extent of the economic crisis has been far larger than that of the 2008 to 2010 financial crisis, states Giles, highlighting that, at the time, a 6 per cent dip in GDP represented the biggest recession in some 70 to 80 years. However, it has also been far faster in retraction and in recovery.

In the two months between February and the end of April, the UK economy lost 25 per cent of GDP, “an extraordinary figure”, admits Giles. The progressive reopening of the economy permitted a fairly rapid bounce back to the point where, at the end of September, the economy was roughly 10 per cent of GDP below pre-pandemic figures in February.

“10 per cent of GDP is still bigger than the whole of the financial crisis but the recovery was faster. The start of the recovery was definitely V-shaped,” he says.

Acknowledging the delayed analysis of GDP figures, Giles points to use of more reactive data such as spending on cards, which suggests that a decrease in spending driven by the further lockdowns in November was nothing like that which had originally been seen in April. This, he suggests, indicates that the inevitable Q4 economic dip in GDP will be much milder.

Giles highlights that what recovery has been swiftly achieved has been enabled by the protections offered by the UK Government, including the furlough scheme and business supports. This however, has had a dramatic impact on public finances.

“In the global financial crisis we got to a level of deficit of about 10 per cent of national income. We’re going to be around double that this year, representing the biggest record deficit in peace time,” he says.

Giles highlights government expectations of public sector net borrowing of around £50 billion at the turn of 2020, around 2 per cent of GDP. However, government supports coupled with tax revenue losses are now expected to see that figure grow to an unprecedented level of just under £400 billion, according to figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR).

“This is an extraordinary amount and it is something that we will have to deal with if it continues,” explains Giles. “If it is a one off then we’ll have increased our national debt but we will service that debt and it will not have to be repaid. However, the big question is how much of this extra borrowing is persistent and might need to be closed through lower public spending or higher taxes.”

Unemployment

Discussing what the economic impact of Covid means for unemployment and jobs. Giles, again, highlights that Government initiatives have protected against initial unemployment rate rise projections of between 4 per cent and 13-15 per cent. Now, forecasts are suggesting that the ending of furlough schemes will produce a more likely rise to around 7-7.5 per cent, probably peaking around the summer of 2021.

“The unusual element is that we will likely see a strong recovery, while unemployment simultaneously rises, as the economy shakes out the companies that haven’t ultimately survived,” adds Giles, who explains that an unemployment rate of 7.5 per cent is not huge in UK historical terms.

Outlining the cohort which will be most affected by the rise in unemployment, the economist suggests that rather than those who are or were employed at the start of the pandemic, it will be those hoping to enter the labour market who will be most affected. “Higher unemployment is coming from a lack of hiring, not firing,” states Giles. “Anyone coming out of school, university or college are finding it much harder to get into the labour market and that’s where you see the big rise in unemployment.”

On a regional basis, the unemployment trend is set to be distorted. While London usually has the greatest protection from economic shocks, October’s claimant count saw the English capital rise to the top of all UK regions and inevitably, rank as the largest increase in the last year.

Internationally, the UK’s budgetary response to coronavirus has only been surpassed by Canada in the G7 but as Giles explains, this level of spending has not delivered the health or economic outcomes that may have been hoped for. Of the G7, the UK is second only to Italy in the highest coronavirus death rates per 100,000 of the population and it is on course to record the largest economic contraction of GDP among the G7 in 2020.

“The concern is that our spending has been very effective in keeping people attached to their companies but hasn’t been very effective in either addressing the pandemic, so far, or in repairing the economy,” explains Giles

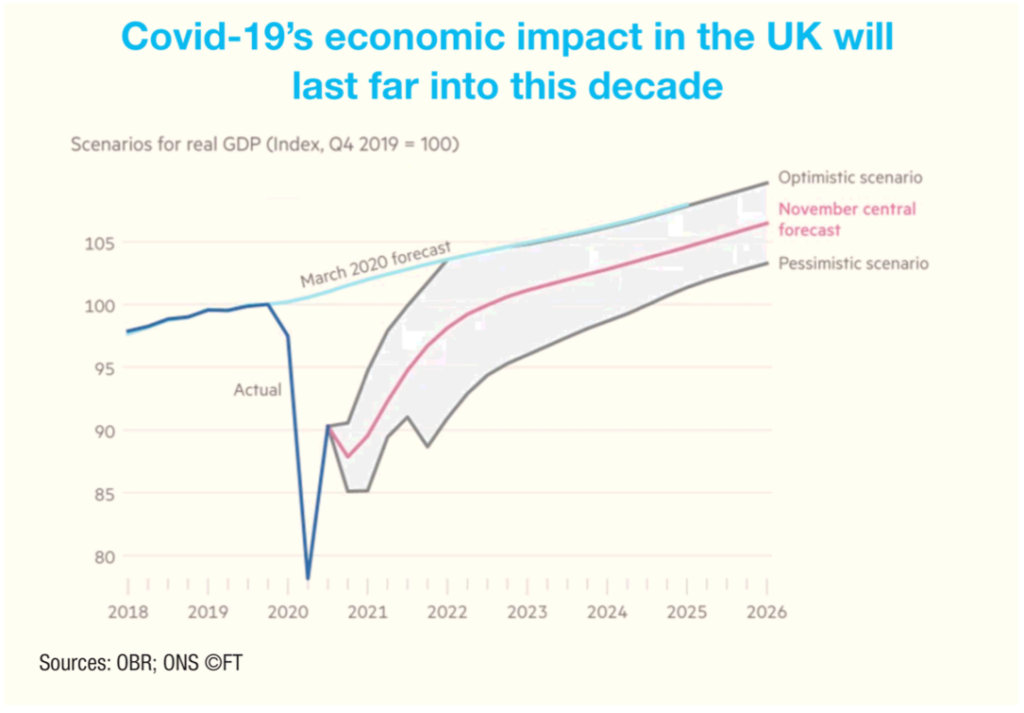

The OBR forecasts a steady recovery from the 10 per cent reduction in GDP by around 7 per cent by 2022/2023, however, a shortfall of 3 per cent of national income (£60 billion) appears persistent far into this decade. The OECD estimates are closer to 5 per cent.

Giles identifies a number of potential reasons for this shortfall including a lengthy recovery for retail, particularly physical spaces, and air travel, where a permanent hangover could exist.

Additionally, he points to a skills challenge. Where people have built up skills in economic areas which no longer exist, efforts to retrain individuals generally take a long time and often lead to less economic productivity.

“Those are the long-term scars discussed by economists. 3 per cent is not a huge number, it’s a lot less than we think the scars of the financial crisis are but it does mean that there is likely to be a hangover from the crisis and that loss of output compared to where we wanted to be has a knock on effect to tax revenues,” says Giles.

Analysing day-to-day public spending figures from the OBR, Giles highlights the austerity drive in the previous decade to get back into surplus in 2018-19. That surplus lasted only one year and the current deficit is much larger than ever before, almost treble that of 2009/2010.

The economist accepts that this deficit is likely to decrease quickly because a large proportion of it is emergency spending to deal with the pandemic, however, forecasts predict a deficit beyond the next UK election of some £30 billion of where the UK Government wanted to be, meaning a likelihood that taxes will have to rise in the future.

Giles doesn’t expect tax rises any time soon, outlining his belief that it would be the wrong time to do it given that zero interest rates meaning an inability to offset tax increases easily, but adds: “long-term scarring will require measures to repair public finances.”

Speaking prior to January 2021, Giles adds the potential of a no deal Brexit would potentially reduce GDP by a further 2 per cent, 1.5 per cent of which would be persistent.

Concluding, he says: “It has been an extraordinarily deep recession and one that we have recovered from very quickly so far but we still have a long way to go and there are likely to be some levels of persistent problems, which will mean there is going to be some hangovers which will be with us for some time.”