Burned: Accountability and derision

‘Burned’ author Sam McBride writes in agendaNi about the role of the civil service in Northern Ireland’s largest political scandal and the accountability for those involved.

Civil servants are uniformly lazy pen-pushers, corrupt, feckless and incompetent – and whenever they get caught, nothing happens.

It’s not true, of course. In ‘Burned’, my book telling the remarkable story of the RHI scandal, I stress that there are in the civil service fine people of high moral character. But sometimes you’d think the Northern Ireland Civil Service was doing its best to reinforce the worst stereotypes about it.

The cash for ash scandal has urgently reasked a longstanding question: How do bureaucrats deal with one of their own when they have acted in ways which would merit at least discipline, and perhaps dismissal, in the private sector?

In many people’s minds, the story of RHI is about Arlene Foster, Jonathan Bell and shadowy DUP special advisers.

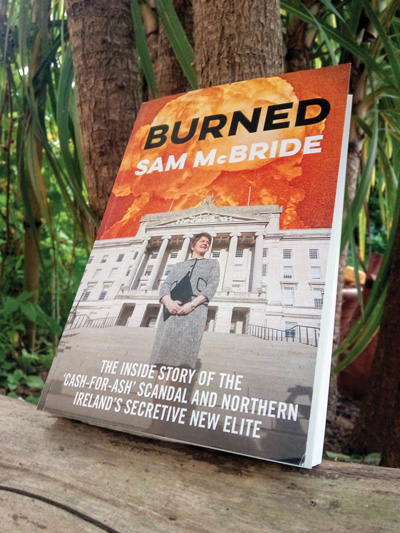

Those all played key roles in the calamity which toppled devolution. For that reason, after initially not planning to put Arlene Foster on the cover of ‘Burned’, I changed my mind. There is an important democratic principle that a minister cannot wash her hands of what happened on her watch, especially when she was happy to take credit for the scheme when she thought it was popular, despite the fact that she now says it was overwhelmingly the work of her civil servants.

However, to anyone who – unlike Foster, who has said that she will not read the book, but may have someone read it for her – opens the pages of ‘Burned’ and reads how shockingly this massive project was handled by official after official, it will be clear that what has happened here goes far beyond the perception of bad behaviour by DUP figures.

Take one example which was passed over quickly at the public inquiry but which I think is one of the most significant elements of the entire story.

Stuart Wightman was the official in charge of DETI’s Energy Efficiency Branch and responsible, along with Seamus Hughes who sat under him, for much of the oversight of RHI. There are multiple elements of their work which are jaw-dropping. Hughes, for instance, was promoting RHI long after he knew that it was out of control and at the same time desperately attempting to rein it in.

Wightman and Hughes were both briefing the renewable industry and Moy Park that the scheme would soon be less lucrative, yet later seemed astounded that there was a spike in applications, organised by many of those being briefed by them.

But one action by Wightman went beyond that in its significance. On the morning of 17 November 2015, Wightman appeared as a witness before the Assembly committee which scrutinised his department.

It was a highly irregular situation. Just minutes before legislation which would make the subsidy less lucrative was to be introduced on the floor of the Assembly, he had arrived to be quizzed by the committee, a process which would normally take place weeks in advance.

Only five of the committee’s 11 MLAs were present for a discussion which followed consideration of the committee’s Christmas card list. But while there are serious concerns about the aptitude of many MLAs to perform their roles as legislators, what Wightman would say that morning would make it difficult to blame MLAs for failing to understand the disaster.

The mid-ranking official seemed nervous. His hands shook slightly and he fidgeted somewhat as he spoke. What he was telling MLAs seriously misled them to the point of being preposterous.

“There is an important democratic principle that a minister cannot wash her hands of what happened on her watch.”

During an appearance which was shorter than a television ad break, Wightman led the committee to believe that stalling on the issue could halt investment, when in fact as he knew the critical problem was that further delay would lead to the already vast spike in applications increasing still further.

The committee chairman, Patsy McGlone, began by asking Wightman: “So, why’s it so urgent?”

Wightman replied: “The reason for the urgency was that we were originally aiming for 4 November and we’ve been very open with the industry about that date … so we’re keen that there’s not a hiatus out there in terms of the industry because I know because we’re changing the tariff banding there are a number of installers holding off on new installations. Also, in terms of value for money, we’re obviously keen to obviously make the changes as soon as possible in terms of affordability of the scheme going forward [sic].”

“It is a grave thing for a public servant to mislead democratically-elected legislators about a matter of public interest.”

Contrary to Wightman’s evidence, the original date had not been 4 November but early October. And although he mentioned value for money and budgetary considerations, there was no emphasis given to the seriousness of the situation.

Wightman was effectively telling the MLAs that the Department was attempting to facilitate turning on the tap of green investment when he knew that they were desperately trying to turn off the tap.

Having been given a misleading picture, the committee did nothing to probe the glaring holes in his story and unanimously nodded the changes through. Wightman’s appearance, which ought to have been lengthy and difficult, lasted just two minutes and 13 seconds.

It is a grave thing for a public servant to mislead democratically-elected legislators about a matter of public interest. How can legislators take meaningful decisions if they are being misled?

More than three years later, in common with every civil servant involved in RHI, Wightman has not been disciplined. Rather, he has been promoted (as has Fiona Hepper, who admitted misleading Foster as RHI was being designed).

Wightman of course deserves a fair hearing (he declined to answer my questions seeking his side of the story) and due process must take its course. After more than three years, the civil service argues that it cannot take disciplinary action against any of those involved until the conclusion of Sir Patrick Coghlin’s public inquiry. However, there was little evidence of alacrity even prior to the inquiry’s establishment.

What in the private sector would be resolved, for the benefit of both sides, within months, routinely seems to drag on for extraordinary lengths of time in much of the public sector.

There will be complex explanations for what now happens, just as Hepper had a complex explanation in her head for how it was logical to pay an uncapped subsidy for heat which was higher than the cost of fuel.

But sometimes common sense appears entirely absent, and that is now harming the entire institution. By not being seen to deal with officials who obviously have a case to answer for their handling of this scheme, all civil servants are in danger of being held in derision.

Delphic foresight is not required to see where this will go if unchecked. Politicians were here years ago. Having seemed incapable of holding each other to account, politicians are increasingly overseen by genuinely independent bodies – and have seen their reputations tarnished to an extent which now undermines democracy itself.

Civil servants are not uniformly lazy pen-pushers, corrupt, feckless and incompetent.

But that is what the public will soon think unless they can be seen to be held to account.

About 1,900 years ago, the Roman poet Juvenal asked: “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” – who will guard the guards themselves.

In Northern Ireland, with a civil service governing without any democratic mandate or accountability, that question is apposite and urgent.

Sam McBride is author of The Sunday Times’ bestseller Burned: The Inside Story of the ‘Cash-for-Ash’ Scandal and Northern Ireland’s Secretive New Elite