Brexit: The financial settlement

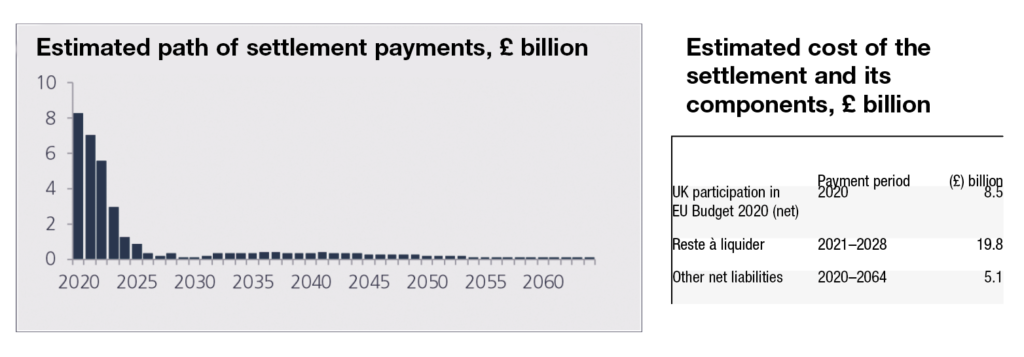

The UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) estimates a divorce bill of around £33 billion for the UK as a result of Brexit, with payments being made into the 2060s.

The finances relating to Brexit have been much speculated. From Boris Johnson’s bus slogan claiming the UK was sending the EU £350 million a week that could have been redirected to the NHS to claims that the divorce bill would see the UK paying for EU services for which it could not avail, the ‘cost of Brexit’ remains an elusive figure.

The withdrawal agreement between the EU and the UK acknowledged that the UK retained financial obligations that arise out of the UK’s participation in the EU budget and the broader aspects of its EU membership.

The financial settlement set out which financial commitments will be covered, the methodology for calculating the UK’s share and the payment schedule. While there is no definitive cost to the settlement, given that the final cost to the UK will depend on future events, including exchange rates and EU budgets, the UK estimates a net cost of around £33 billion.

Three principles guided the financial settlement between the EU and the UK, these were:

- that no EU Member State should pay more or receive less because of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU;

- that the UK should pay its share of the commitments taken during its membership; and

- that the UK should neither pay more nor earlier than if it had remained a member state, meaning that the UK will make payments based on the outturns of EU budgets.

There are three main elements of the settlement. The first, which has now passed but remains relevant because of the longer-term implications was that the transition period would see the UK pay into the EU budget as though it were a member state. This meant that the UK also had the same access to structural funds as other member states, the outworkings of which stretched to the end of 2020.

The second was an acknowledgement that EU annual budgets commit to future spending, the cost of which is not met in a single annual contribution. Given that the UK was a full member state, it will continue to make contributions to the EU’s outstanding commitment which were live on 31 December 2020. In the same vein, UK recipients will continue to receive funding for outstanding commitments made to them up until the same date.

Thirdly, financial liabilities of the EU, such as staff pensions, will continue to be shared by the UK. The OBR estimate that the UK will have contributed around £12 billion to EU pensions through the financial settlement once the final payment is made. These largely relate to liabilities at the end of 2020 but also include “any materialising contingent liabilities”. However, the UK is entitled to a share back of some assets, including capital paid into the European Investment Bank (EIB).

A briefing from the House of Commons Library outlines the details and stipulates that not all elements of the settlement fit within these elements. For example, the UK will continue to contribute to the EU’s main overseas aid programme, the European Development Fund, a programme funded directly by member states rather than through the EU budget.

Not included in the financial settlement is the cost of the UK’s decision to continue to participate in some EU programmes following the conclusion of the transition period. The UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement stipulated the UK’s continued participation in a range of programmes including Horizon Europe, the Euratom Research and Training programme, the International Thermonuclear Experiment Reactor and Copernicus. The contributions for taking part in EU programmes are part of the future relationship and not the financial settlement.

The financial settlement, the OBR estimates, will be made over a 46-year period ending in the 2060s, however, much of the cost will come in the early years. It’s estimated that just over 70 per cent of the net payments will have been made by 2023, with payments after 2031 averaging around £200 million per year.