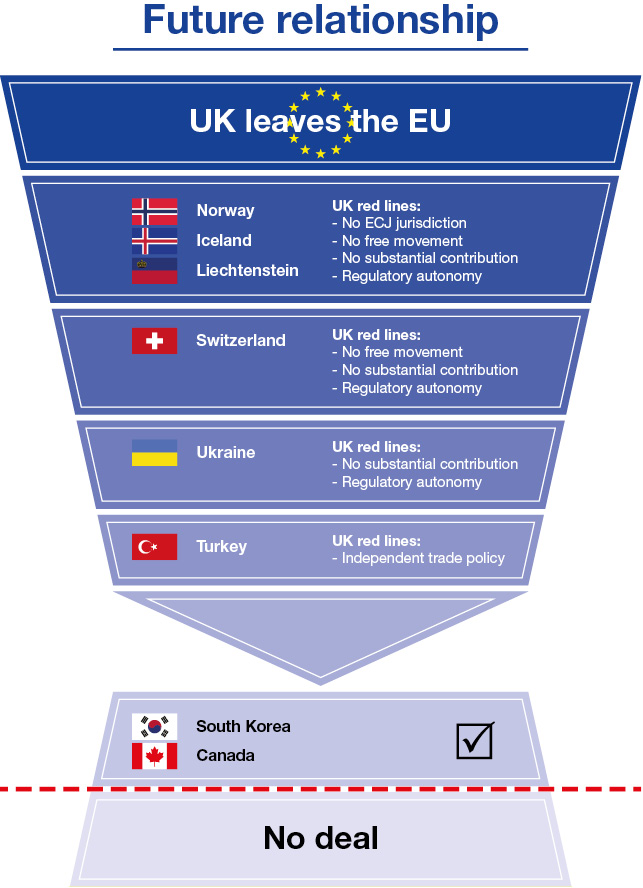

‘Bespoke’ deal not an option

As pointed out by many commentators following the triggering of Article 50, the timeframe for which Britain has to strike a trade deal with the EU makes a unique trade agreement highly unlikely. Instead, the best Britain can hope for, in order to avoid a cliff edge exit into WTO terms, is a tailored approach to one of the existing EU trade deals across the globe.

The Westminster Cabinet, in particular David Davis, have offered some indication to the type of deal they would like to see. The EU on the other hand have been firm in their language that Britain will not be allowed to ‘cherry pick’ its alignments and access to the EU markets.

Below are some of the models which the Britain may seek to build upon or tailor in the coming months.

Canada

Canada

A Canada-style deal appears the most likely and is the one suggested by the EU, taking in to consideration the UK’s red lines. Although there are some variations, the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) is largely similar to deals struck with South Korea and Japan. The deal, which took seven years to conclude, removes most custom duties on exports and a large portion of tariffs on agricultural

products – not covering sensitive products such as eggs or chicken.

The deal would largely appease brexiteers, removing any obligations to pay into the EU budget, agree to the four freedoms, or abide by ECJ rulings. However, crucially, the CETA does not guarantee firms an EU passport for financial services. The deal also does not remove non-tariff barriers such as EU rules of origin requirements. Overall, the deal, while positive in some areas still puts significant limitations on access to the EU markets currently enjoyed within the single market and customs union.

Ukraine

Ukraine

Less-widely discussed than the two opposite ends of the deal spectrum, Canada and Norway, the EU-UK association agreement does not involve membership of the single market or the customs union. Instead it offers extensive market access for goods and services, encouraging close customs co-operation. The deal requires regulatory alignment in areas such as competition, state aid and public procurement and foresees co-operation on foreign, security and defence policies, justice and home affairs, scientific research and many other areas (source: FT).

Instead of freedom of movement the deal offers visa liberalisation and a work permit scheme. However, such a deal fails to offer a solution to the Irish question and also gives a more elevated role to the European Court of Justice than the UK wants.

Switzerland

Switzerland

To adopt the swiss-model, the UK would have to row back on some of the key red lines in has laid out. Switzerland currently holds membership of the European Free Trade Association but not the European Economic Area (EEA). Although the Swiss enjoy good access to the EU market, this access is governed by a series of bi-lateral agreements and excludes financial services. Switzerland also pays a contribution to the EU, something that would undoubtedly be opposed in the UK. Another major blockage is that the Swiss-model requires free movement of people.

Norway

Norway

Originally mooted as an original solution to the UK’s trading future with the EU, it quickly became clear that hard brexiteers would not except what they view as ‘Brexit lite’. The Norway model is the closest deal to EU membership and largely offers access without representation. As a member of the single market it contributes to the EU budget and strictly follows its regulations and standards. The country is exempt from EU rules only in the areas of agriculture, fisheries, justice and home affairs.

As well as accepting the four freedoms of the EU, many in the UK take issue with having to follow EU rules without any involvement in shaping them.