A skilled and supported workforce

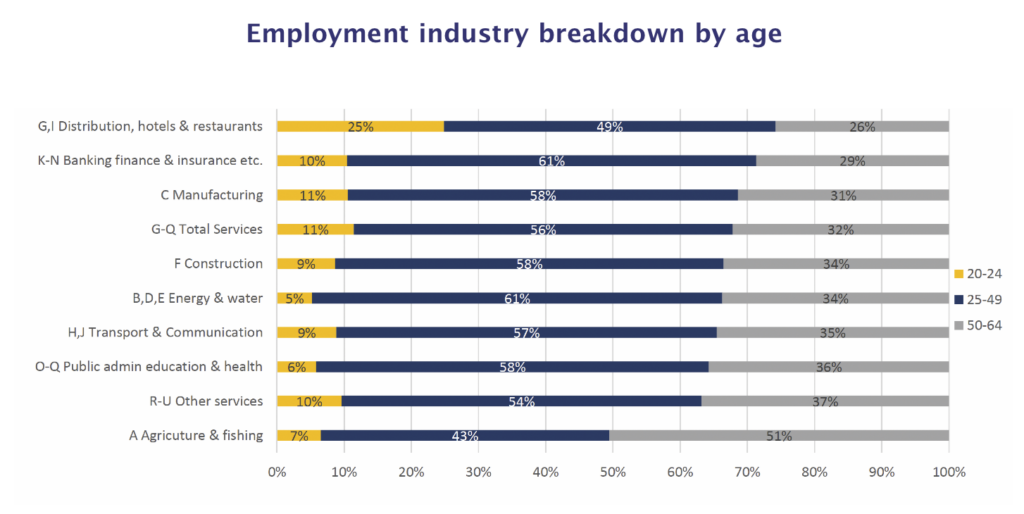

Studies by the Department for the Economy have highlighted the need to upskill older workers and ensure that younger workers are attracted into the labour market in the aftermath of Covid-19.

With an ageing population and increasing global competition, combined with a need for Northern Ireland to reach net zero, many experts believe that people need to be encouraged to work for longer, particularly in sectors such as housing, with retrofit requirements demanding a significant output from this sector with an average workforce age above the age of 50.

More than one-third of the population of Northern Ireland is over the age of 50, with the 50+ demographic accounting for slightly below 700,000 people, which is just under 37 per cent of the population of Northern Ireland.

According to NISRA’s most recent population projection, published in 2021, the number of older people is expected to increase year-on-year. NISRA predicts that the 50+ population will rise by roughly 208,000 people (30.3 per cent) by 2070. This increase will mainly be shown in the 65+ age group as people are living longer.

Managing an older workforce

The Department for the Economy’s Older People Inequalities in the Northern Ireland Skills System report outlines four challenges to ensuring that Northern Ireland can successfully integrate older people into the workforce and thus ensure a more stable labour market for the Northern Ireland economy:

Upskilling: “As people are living longer, this increases the percentage of the workforce aged 50 and over. Companies will have to adjust to this ageing workforce. They will need to adjust how they attract, manage, and develop workers. With the constant advancements in technology, training, and upskilling has never been as important to make sure staff have the required skills to keep up with these advancements.”

Reskilling: “Some workers will also have to consider changing careers due to automation as well as moving away from manual labour jobs to less physical jobs.”

Flexible working: “Changes needed to working patterns, either reducing to part-time hours, offering alternate working patterns outside of 9-5, and hybrid or home working.”

Support for health and wellbeing: “Employers to offer better support for health and wellbeing to all employees but will be needed more in 50 and over age group.”

A further problem highlighted in the Department’s report is that employers in Northern Ireland are less likely to employ someone aged 50 or above. Additionally, the report states a correlation between larger companies and an increased likelihood of recruiting a worker aged 50 or above. Only 42 per cent of employers surveyed were open to a large extent to hiring somebody aged 50-64. DfE also reports that even fewer companies are open to hiring anybody aged over 65 (30 per cent), with almost one-fifth (18 per cent) of these organisations not open to the idea at all.

On the other hand, Northern Ireland has the highest rate of early entrepreneurship out of the four UK regions and nations, with 8 per cent of those in the 55-64 demographic in Northern Ireland involved in early-stage entrepreneurship activity as of 2021.

If older people are to be encouraged to remain in the labour market in Northern Ireland, the key to unlocking this will be to ensure that there is a strong level of training, with workers being equipped with a skillset which is dynamic enough to meet the evolving needs of the Northern Ireland economy.

The next generation of workers

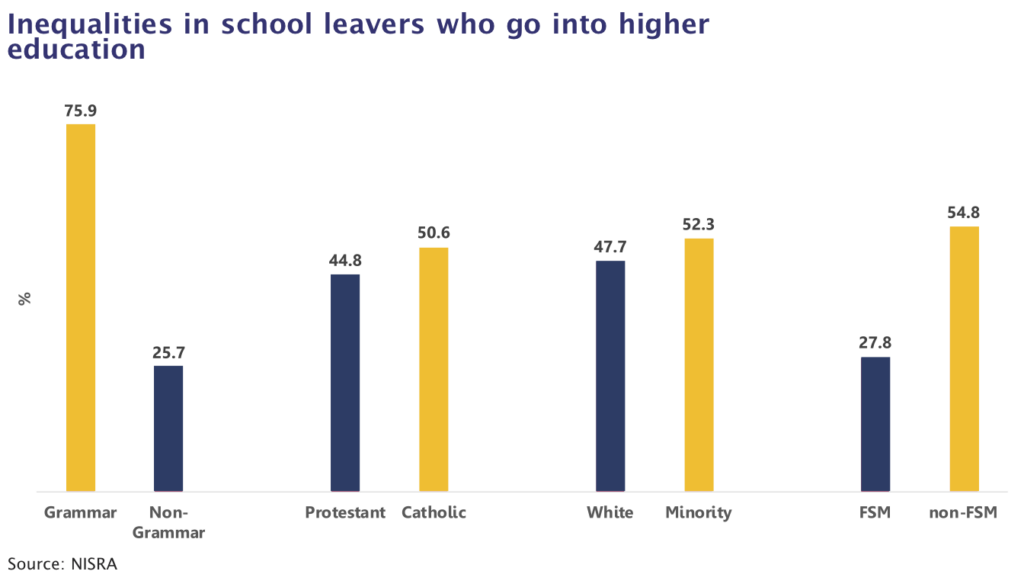

The Department for the Economy’s Young People Inequalities in Northern Ireland report explains the differing set of circumstances facing Northern Ireland’s young people compared with the challenges being faced in equipping older workers.

Whilst the challenge in integrating older people into the workforce lies in upskilling, there are a number of multi-faceted factors which are influencing the successful integration of young people into the Northern Ireland labour market.

Additionally, there is a wide discrepancy in workers being paid the living wage. Whilst every age demographic from the age 25 and above is paid a real living wage at a rate of 85 per cent and above, only 58 per cent of workers aged between 18 and 24 are paid a real living wage.

“For young [people] that work, wages are lower. For those available to work, unemployment is higher,” the report states.

The report also hints at potential alienation for young males, with wide gaps in educational attainment between male and female students in all school settings. However, although female students are getting better A-level results than their male counterparts, there remains a wide gap in those studying narrow STEM subjects at higher education level, with 49 per cent of male students studying narrow STEM subjects compared to 19.6 per cent off females.

The NISRA population projection, published in 2021, estimates that, in 2032, the 18-24 demographic will reach of a peak of comprising around 13 per cent of the population of Northern Ireland, before subsequently entering long-term decline. Currently, said demographic accounts for around 10 per cent of the population of Northern Ireland.

The report examines the psychological impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on young people’s hopes and aspirations. Worryingly, the report states that a majority (51 per cent) of people in the 18-24 age demographic “feel their aspirations are lower due to global events since 2020”. Additionally, 33 per cent of young people feel that they “will no longer achieve their career goals”, and 36 per cent feel that their “job prospects will never recover from Covid”.

The report additionally makes use of a survey by The Prince’s Trust, which further emphasises an apparent sense of hopelessness which is engulfing many young people of working age. Only 43 per cent of participants in the study believe that their education has equipped them with the skills they need to get the job they want.

Furthermore, almost two-thirds (64 per cent) say it is “not easy to get a good job these days” and 29 per cent report that they have struggled to get interviews. In addition, 19 per cent of young adults say there are not the jobs available in their local area.

Looking at attitudes to work, 13 per cent of respondents the study state that they are currently unemployed, with a further 3 per cent economically inactive. Additionally, 9 per cent of those unemployed (around 1.2 per cent of young people) say they never intend to start working.

The results from the report show that there are different behaviour factors to take into account when considering how best to integrate young people into the labour market. Based on the results of the Department for the Economy’s report, there is an apparent sense of hopelessness among young people outlined in The Prince’s Trust report, in addition to the 42 per cent of people working aged 18-24 who do not earn a real living wage.

Decision-makers face important choices in terms of how to equalise these discrepancies and ensure that more women work in STEM, as Northern Ireland becomes more reliant on this sector in the effort to ensure net zero in line with its climate change commitments.