A meeting of minds

In 1972 a fresh-faced film producer travelled from England, camera in tow, to meet the then youngest MP, determined to bring the civil rights campaign in Ireland to the highest levels of Government. Almost 50 years later David Puttnam joined Bernadette McAliskey on stage at the MAC in a fascinating conversation to look back at their encounter and the different pathways that events of the time set them on.

Puttnam would go on to be a renowned, award-winning film producer with a vast portfolio that included not least the Academy Award-winning Chariots of Fire, but amidst his feature films he produced a number of documentary-type films.

One of those films was his documentary short ‘Bringing It All Back Home’, which featured the 21-year-old MP for Mid Ulster Bernadette McAliskey (née Devlin) and her efforts to bring the campaign for civil rights, raging in Ireland, to the doorstep of the then British Government.

The film’s main focus is McAliskey’s role as speaker at an anti-internment march at Magilligan Strand in Derry where violence erupted, including the use of rubber bullets and CS gas by the British Army. John Hume accused the soldiers of “beating, brutalising and terrorising the demonstrators”.

Not known by many at the time, the event and the violent suppression of protest by the British Army that day would serve as a pre-cursor to the Troubles. The following weekend was Bloody Sunday.

McAliskey, having re-watched the film, quite poignantly states: “Looking back, how did no one logically understand the inevitable permutations and combination of the consequences that were being played out in front of us. If we had been able to step back an analyse those events, we would have known they were going to kill us on Bloody Sunday.”

The film also has a broader look at the efforts to bring the civil rights campaign to the streets in England. Puttnam, now a peer in the House of Lords, admits to having joined some of the anti-internment marches in his home country.

Setting out his reasoning for attending the marches and for ultimately making the film, Puttnam outlines how a raid on the offices of his friend, Tony Elliot, founder of the then little known publication ‘Time Out’ by Special Branch, horrified him. The incident coincided with a fairly recent realisation by Puttnam that cinema and film were much more than the entertainment media that he had grown up loving.

“In the mid to late 1960s I saw a film in the National Film Theatre called the Battle of Algiers which changed me and something about the conversation I had with Tony echoed that film. We’d been through the Vietnam marches and the marches against apartheid in South Africa, so the concept of mass mobilisation wasn’t new to me. But what was new to me was that in my own country things were going on that I had marched against in respect to other countries.

“I was an active unionist at the time and it (police efforts to supress anti-internment marches) was a shock. That’s what led us to bundle together and to fly out and engage with Bernadette.”

Puttnam, now a resident to Skibbereen in County Cork, has wore many hats in his various roles from film producer to educator, to environmentalist and even as a digital champion, all the time seeking to correct injustice. Although maybe not obvious at first, parallels can be drawn with McAliskey, who has also furthered her role as an educator and continues to campaign against injustices, including migrant rights.

Interestingly, they shared a complementary outlook on the need for critical and complex thinking from government to find solutions – neither held high hopes for the current generation of political classes.

McAliskey points to the treatment of the Irish ‘problem’ by the British Government as systematic to how migrants are currently being treated, believing that lessons not learned about the cultural differences in Ireland have prevented any progress on anti-immigrant sentiment.

“Why do people in power and authority not recognises the obvious necessity for systemic and systematic change? The answer has to be they don’t want to,” she says.

McAliskey points to an “appalling vista” at what the Tory Government did to prevent radical social change on these islands and believes that little progress has been made in recognising the flaws in their approach to more recent demands for social change. “You can say ‘for the many, not the few’ as much as you like and will get as far as Jeremy Corbyn,” she states.

Puttnam has also recognised a lack of desire to address the need for change. “Currently we’re in a place where, what is going to be required to navigate through the climate change crisis, through global shifts like Brexit and through migratory issues is an understanding of complexity and a level of subtlety but we are stuck at the moment with a Prime Minister who is emotionally incapable of dealing with complexity and who will immediately look for simple answers.”

He points to the Thatcher era as a starting point for a succession of Prime Ministers who have looked for simple answers, believing the UK has now reached its nadir in this regard with Boris Johnson, who he says “literally despises complexity”. “And yet, the issues we are dealing with are maybe more complex than they have ever been,” he adds.

Focussing specifically on Ireland, he says: “The current political circumstances on the island of Ireland are immensely complex and require extraordinary levels of subtlety, which I get no sense of from the current administration.”

Resonating with McAliskey’s view that there is a lack of will to understand such complexities, Puttnam adds: “Something that struck me throughout the Brexit debates in the House of Lords, which got quite bitter, was the almost wilful level of ignorance that exists in parliament towards the complexities that exist in Ireland.

“It’s as if they can’t, or don’t want to, go there because it requires an ambiguity of thought that is simply beyond this present generation of politicians. How do you change that? The only way is by Irish people collectively saying, ‘the solutions you are proposing do not work for us, therefore, we are going to have our own’.

“I personally think the reunification of Ireland is a historical inevitability, but the issue is how do you get there and how do you get there by injecting enough comfort for everyone.”

Modern activism

The pair also share a similar outlook on the need for greater precision in modern activism. “It’s not enough to be relevant, you have to be precise,” says McAliskey, addressing the use of mass action in the modern era. “Culture eats strategy for breakfast and so if you want to affect sustainable change then there must be a greater solidarity than picking a date, calling a demonstration and calling on all hands to turn up. Unless we can establish a discipline around what we are doing, how we agree to do it and what the parameters of our shared action is, then we are doomed on the progressive and left movement to jump from issue to issue like people who have ideological attention span disorder.”

Puttnam has a similar outlook: “Political capital is rare,” he states, “you need timing and political capital to affect change. It’s okay to prioritise issues of personal importance and for that not to be minimising the importance of something else. Each individual only has a certain amount of headspace and political capital to use.”

McAliskey succinctly condenses the train of thought to say: “We don’t all need to concentrate on the same thing. We spend so much time checking our progress on the sliding scale of serious socialism that we don’t get any work done and we can’t get to the point of solidarity.”

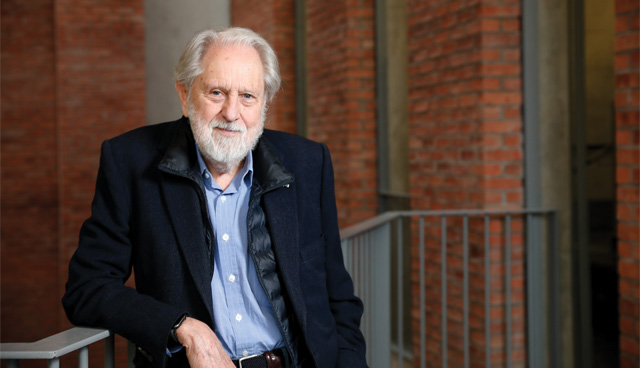

David Puttnam

Puttnam’s career and influence has evolved far beyond those early days of filmmaking. Following an extensive career in film, he was appointed as a life peer in the House of Lords in 1997 and went on to chair the joint scrutiny committee on the Communications Bill. He was successful in informally amending the legislation over concerns around the influence of large media ownership across multiple platforms.

In 2012, he was named Ireland’s Digital Champion by then Communications Minister Pat Rabbitte. However, his current passion is in his role as Chair of the special House of Lords Democracy and Digital Technologies Committee, set up to investigate the impact of digital technologies on democracy.

Following extensive evidence gathering, the Committee recently released a report urging the UK Government to act immediately to deal with a “pandemic of misinformation”, which it argues “poses an existential threat to our democracy and way of life”.

Puttnam himself said that the UK was “living through a time when trust is collapsing”.

“People no longer have faith that they can rely on the information they receive or believe what they are told. That is absolutely corrosive for democracy. Part of the reason for the decline in trust is the unchecked power of digital platforms.”

Puttnam wants to improve the education of younger people to ensure that they can comprehensively assess the origin and validity of information online, an interesting outlook for a filmmaker utilising both fact and fiction.

The producer suggests that both fact and fiction can be useful tools in storytelling. “I teach a seminar on the very topic of fact or fiction and what I try to get across is that fact can inform fiction and vice versa. The example I tend to use is that of The Killing Fields film. In a particular scene the character enters his apartment and on the TV is the real showing of Nixon talking about policy in Cambodia. The deliberate scene was crucial to the film because it destroyed the argument that the film was polemical. Here was Nixon, out of his own mouth, validating the movie. So, it’s a slightly false division and sometimes you have to take liberties.”

Elaborating, he says: “If you are a purist and documentarian then all facts matter but if you’re making a feature film and the overall point you are making about human behaviour or human nature still rings true, then it doesn’t.”

Puttnam accepts that in presenting complex issues on screen, the use of simplification can sometimes be accused of falsification but believes the use of simplification comes down to an individual’s ethical basis.

A good example he recites is a scene in Chariots of Fire where Eric Liddell discovers while boarding the boat to the Olympics that his heat will be on a Sunday, the Sabbath day his Christian beliefs prevent him from running on. In reality, he had received the news in advance of his departure. “Factually it’s false but we needed it to be a moment for the purpose of the film,” explains Puttnam.

Ensuring an understanding of the difference between simplification and falsification is undoubtedly a key element of Puttnam’s interest in digital technologies influence of younger generations.

“I’m most interested in young people having the discipline to check their sources. Instead of just accepting what is easily spoon feed to them. If Wikipedia becomes your encyclopaedia, at some stage you’re going to make a horrible misjudgement about something.”