A low skills equilibrium

Senior economist at the NERI Paul Mac Flynn analyses whether a low skills equilibrium exists in Northern Ireland.

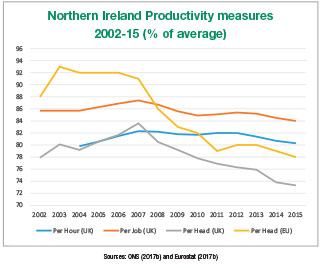

On any number of measures Northern Ireland’s economy is clearly in difficulty. Productivity is the most obvious area of economic weakness and here the trend is increasingly negative. Gross Value Added (GVA) per head in Northern Ireland has never reached the UK average and is currently falling further behind it. In 2006, total output per person in Northern Ireland was 81.5 per cent of the UK average, by 2016 that had fallen to 77.6 per cent.

Wages in Northern Ireland have underperformed the UK average every year for which data is available and Northern Ireland is consistently ranked amongst the three lowest paid regions of the UK. The median weekly wage in Northern Ireland was 92 per cent of the UK average in 2016 up from 91 per cent in 2006.

Another area where Northern Ireland falls behind is in skills and this may be where the greatest policy failure lies. The issue of skills has not suffered from a lack of attention, there have been many conferences, many commissioned reports and many government schemes. Unfortunately, the headline statistics in Northern Ireland remain bleak to say the least. In 2016, 16 per cent of 16 to 64-year-olds did not have a level 1 National Vocational Qualification (NVQ). To have less than a level 1 NVQ means less than 5 GCSEs at A-C grade. The equivalent for the UK as a whole was half that at just 8 per cent.

Productivity is directly linked to skills. A better-qualified and a better-trained worker will be able to produce far more with the same resources than an unskilled worker. Therefore, it is logical enough to draw a line from Northern Ireland’s low skills base to its poor productivity. Similarly, a lack of workforce skills goes much of the way to explaining the chronic underperformance of pay in Northern Ireland.

However, it would be a mistake to focus solely on the level of skills attainment by workers – this is only half of the problem. There is clearly an issue with the supply of skills in Northern Ireland, but much less attention has been given to the demand for skills.

In most cases people will seek out new skills in the hope that they will be rewarded with higher wages. Therefore, the supply of skills in the labour market is directly linked to what people perceive the demand for skills to be. Firms will demand skilled workers if they are planning on investing in new technology or research and development. But firms that want to move up the value chain can only do so if the skills that they require for this are available in the labour market.

In an ideal labour market, the signals of supply and demand are clear and the decisions of economic actors will ensure that the appropriate amount of skills is provided. However, in Northern Ireland it would appear that this situation has broken down. Workers do not feel incentivised to upskill because of a lack of skilled job opportunities. Firms are engaged in low value-added production because they do not feel there is a sufficient skills base to grow from. Northern Ireland is in essence trapped in a low productivity, low wage and low skilled economic dynamic. Economists describe this vicious circle as a low skills equilibrium.

A low skills equilibrium is a situation where a lack of supply and a lack of demand for skills are mutually causal. Workers do not invest in skills because they do not feel that they will be rewarded with higher wages or better paid jobs. This in turn means that firms do not have access to a skilled workforce and do not invest in innovation. Companies can then only offer low-skilled low paid jobs. Workers therefore have no incentive to change their original decisions.

It is difficult to capture a low skills equilibrium in any one single measure but the available data does provide some interesting insights. Despite Northern Ireland’s comparatively low skills base, there appears to be no mismatch between the skills of the workforce and those required by employers. In fact, Northern Ireland has the lowest rate of skills mismatch of any OECD economy. Only 9 per cent of workers in Northern Ireland feel they do not have the level of skills required for their job.

Very few workers in Northern Ireland reported having taken part in training in the last year, and of those that did undertake training of some kind, very few did so for job related reasons. Workers in Northern Ireland are also found to be significantly less likely to identify training opportunities irrespective of whether they actually take part in them or not.

“In an ideal labour market, the signals of supply and demand are clear and the decisions of economic actors will ensure that the appropriate amount of skills is provided. However, in Northern Ireland it would appear that this situation has broken down.”

For firms, the data is equally stark. Firms in Northern Ireland are significantly less likely to have skills shortages or to have vacancies that cannot be filled due to lack of skills. Firms are more likely to have trouble retaining staff because of a lack of opportunities for career progression within the firm than because of competition from other employers. Firms lack the systems in place to identify talent and are found to be more focused on purely price competition.

It would appear then that workers are not incentivised toward upskilling and firms have little appetite for investment; and because these two positions are well matched, nothing is likely to change.

In order to break out of this skills trap, policy must be focused equally on boosting both supply and demand. It is no use launching another programme of upskilling, incentivising people to gain skills that will ultimately get them no further in their career progression. Likewise, it is no use lecturing firms about the need to scale up and invest if the economy cannot provide the skilled workforce such an effort requires.

The solution to a low skills equilibrium is co-ordination. There needs to be a mechanism whereby firms are incentivised toward investment in innovation and where workers are incentivised toward investment in skills. Both of these actions need to happen in tandem.

The UK economy does not do co-ordination well. Decades of deregulation mean that it doesn’t have the institutional levers to affect this kind of change in the labour market. It probably goes much of the way to explaining how Northern Ireland ended up in this situation too.

Breaking out of this vicious cycle of low productivity and low skills will therefore require a departure from current economic policy. It can start small, focusing on one industry and a few firms, but a framework needs to be found whereby firms and workers embark on investment together. Without such a change in policy, our current malaise is only going to become more entrenched.

The full report: ‘A Low Skills Equilibrium in Northern Ireland?’ is available on www.NERInstitute.net