A legal footing?

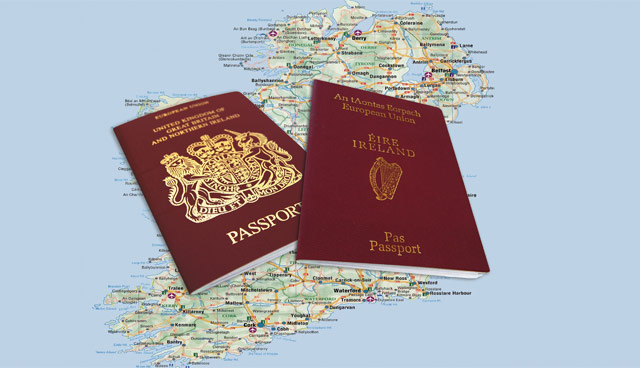

The formal commitment by the British and Irish governments to maintain citizens’ rights under the long-standing Common Travel Area (CTA) has been welcomed but there are concerns about the legal standing of such an agreement in the face of evolving relations.

The Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was signed in early May, formalising co-operation on immigration matters which has existed between the two countries since 1922.

The reciprocal arrangement between Ireland and the UK, the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands allows citizens to travel freely and reside between the two jurisdictions. The agreement also facilitates associated rights and privileges including the right to reside, work, study and access social security benefits and health services; and to vote in local and national parliamentary elections.

However, the bilateral agreement’s legal value has been raised as a concern and potentially problematic in the future, as the CTA agreement will be expected to accommodate complications which arise from Brexit.

Negotiations to formalise the maintaining of citizens’ rights have been ongoing for two years but the Memorandum of Understanding falls short of an international treaty on mutual rights which had been the favoured outcome of most.

Many of the rights agreed under the CTA had been legally underpinned by EU legislation when both countries joined the bloc in 1973, however, with the UK’s future relationship with the EU still uncertain, there exists an ambiguity around the assumptions of the CTA now, and into the future.

Agreements under the CTA were also built into the Good Friday Agreement, fortified by joint EU membership, and the Tánaiste Simon Coveney said upon the memorandum’s announcement that the CTA “underpins the Good Friday Agreement in all its parts”, a claim that will certainly be put to the test as Brexit throws up more and more challenges to the relationship between the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

Notwithstanding Brexit, further challenges exist that have yet to be addressed and seem unlikely to be addressed without a formalised and rock-solid CTA, such as the ongoing case of northern-born Irish citizen Emma DeSouza. Concerns abound despite recent promises from the administrations in both London and Dublin to address issues around immigration and citizenship. The DeSouza case has exposed the British Government’s failure to legislate the right to Irish citizenship for those born in Northern Ireland into their laws and raises further questions of what status those who have both Irish and British citizenship, whether knowingly or unknowingly, could or should claim based on where they reside.

While the CTA agreement covers personal rights such as freedom of travel and extends to education and training, such as EU level fees and SUSI grants for UK students in Ireland, the agreement does not extend to goods and services and how they will be affected once Brexit’s impact becomes a clearer reality.

After the announcement, the Conservative MP and Deputy Chair of the Brexit-supporting European Research Group Mark Francois said that the agreement showed that it was possible to maintain “normal” relations between Britain and Ireland and “why the dreaded backstop has really been unnecessary from the word go”. Given that the backstop is almost exclusively concerned with trade, goods and services, these claims are amiss and do not reflect the reality of what any CTA agreement drives at.

For the CTA to guarantee that “nothing will change”, as both Coveney and David Lidington MP promised, the agreement will most likely need to be subject to regular introductions of new legislations in either country in a manner similar to the Nordic Passport Union.

For the CTA to guarantee that “nothing will change”, as both Coveney and David Lidington MP, Minister for the Cabinet Office and the Prime Ministers

de facto deputy, promised, the agreement will most likely need to be subject to regular introductions of new legislations in either country in a manner similar to the Nordic Passport Union. Given that the tightening of Britain’s borders was one of the major arguments put forward by the successful Leave campaign, how that tightening will exclude Irish citizens will need to be addressed, likewise Irish laws for non-EU citizens will likely need to be altered for British citizens post-Brexit.

Speaking after the announcement, Fianna Fáil Spokesperson for Brexit, Lisa Chambers TD, said that she welcomed the agreement, but expressed reservations over its shaky legal basis. “The reality is that the outcome and shape of Brexit is unknown, and I would have preferred if greater legal certainty had been given to the CTA to guarantee the status quo into the future,” she said. “The CTA is an intrinsic part of the fabric of UK-Irish relations and whilst this MOU is welcome, I believe greater consideration should have been given to making this an internationally binding treaty.

“The threat of a no deal Brexit has receded somewhat but there is no room for complacency when it comes to protecting our country’s interests. It is imperative that we secure the best outcome for Ireland and do all we can to maintain existing arrangements and ensure in as much as feasibly possible that they are on a legally sound footing.”

Questions remain over the exact status of Irish citizens in Britain and vice versa due to the agreement’s non-binding nature. For example, it is unclear whether access to public services will be provided to them as de facto citizens or as favoured immigrants. It is also unclear what, if any, limitations have been placed on the provision of such services.

In a statement announcing the agreement, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade said that the MOU was the “culmination of over two years work and codifies the shared principles and common understanding between Ireland and the UK of what the CTA entails and covers” and that it “reaffirms the existing CTA arrangements” and “recognises the shared commitment of both to protect the associated reciprocal rights and privileges”. Notably, the MOU is referred to as an “enabler of the cross-border freedoms central to the lives and livelihoods of the people of Northern Ireland and the border region”. Tánaiste Coveney called it a “practical demonstration of the enduring strength of the British-Irish relationship and of our people to people ties”.

How those ties will be tested and how they have been protected by the signing of the MOU will only become truly clear when Brexit and its implications finally come to pass.