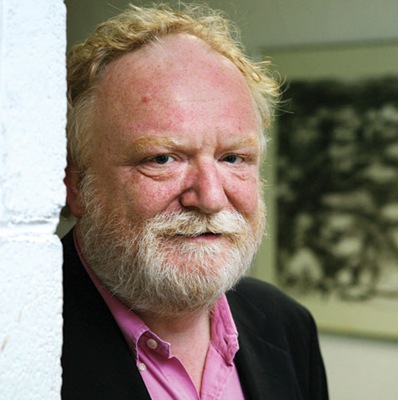

Frank McGuinness interview: waiting for the spark to come

Frank McGuinness, famous Donegal playwright and Professor of Creative Writing at University College Dublin, takes time out from preparing lectures to tell Meadhbh Monahan about the events in his life that have helped shape his work and how he is still “terrified” to watch his plays being performed on opening night.

Suicide, homosexuality, death and war. Frank McGuinness has dealt with these topics and more throughout his illustrious 27 year career.

Born in Buncrana, on the Inishowen Peninsula, County Donegal, McGuinness’ most famous plays include: The Factory Girls, Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme, Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me (based loosely on the experience of Brian Keenan and the other hostages in Lebanon) and Dolly West’s Kitchen. He has also adapted Greek tragedies Hecuba, Phaedra and Oedipus, and has written screenplays for Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa and a TV film about assisted suicide called A Short Stay in Switzerland.

Childhood

Growing up in rural Donegal did not inspire McGuinness to become a playwright because there were few opportunities apart from Drámscoil and local pantomimes. However, when he “got the buzz” for theatre during his time as English teacher in the University of Ulster at Coleraine, his hometown of Buncrana became the setting of his first play and he used his childhood experiences as material for his work.

The Factory Girls is set in a shirt factory in Buncrana and tells the story of how a group of female employees organise a sit-in when faced with losing their jobs.

“My mother, my grandmother and my aunt all worked in a shirt factory so it was inevitable that that would be the first subject of my first play,” McGuinness says.

While he was growing up he was in “a very strange position” because “the vast majority of the labour-force in Buncrana were women.” McGuinness notes: “This was not usual in the Ireland of the 50s and 60s.”

Another factor which influenced McGuinness as he grew up was his extended family.

“There were an awful lot of cousins and aunts and uncles and we all congregated at our grandmother’s house.”

As a result McGuinness was “exposed from a very early age to a lot of adult conversation”. He remembers how he had to “attune my ear to the subtlety of adult speech very quickly”. This gave the writer “an awareness of how people talk, what they talk about, and more importantly, what they don’t talk about.”

The Other

Through visiting Derry, his “natural” capital city, McGuinness gained “a very strong awareness of difference and the other.”

He states: “That can only be an advantage to a writer, when you are aware that there is more to this world than yourself.”

McGuinness agrees that his awareness of the other had some influence in his writing Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme. But the strongest factor influencing that play was his experience of working in Coleraine.

“That was my first time living in a predominantly Protestant community. I had never really been exposed to their cultures and the differences within their culture and also the key dates in their history.”

McGuinness notes that “the Battle of the Somme was a key date in Irish history as well as a significant day in Ulster Protestant history.”

He recognises that “in terms of impact, it was as powerful as Easter 1916 was for the nationalists” and laments that as a pupil in the southern education system he was “kept in the dark about the tremendous importance of that date.”

Sexuality

The play follows eight men from the 36th Ulster Division on the French battlefield and is told through the memory of the sole survivor, a gay upper-class Protestant called Pyper.

McGuinness acknowledges that this play explores both war and homosexuality and, as a result, it received mixed reviews.

“It received pretty positive feedback because at the time people were willing to talk about it and wanted to recognise how important it was. There were many people who had uncles and fathers who fought and died in that war still around in the eighties.”

He has received negative feedback due to the theme of homosexuality in some of his plays and to this he says: “I genuinely don’t have time for bigots. Bigotry is [cleverer] now and more disguised. Bigotry can learn to change its spots but I can smell it very easily. I now refuse to have the good manners to deal with them because they have no manners.”

Coming to terms with his own sexuality at an early age “didn’t really have a bearing” on his plays.

Coming to terms with his own sexuality at an early age “didn’t really have a bearing” on his plays.

“The Iris Robinsons of this world, I have given up trying to have any conversation with. They are lost in their own loneliness and their own sorrow. I think there is a terrible wound inside people who hate homosexuals and I can’t heal it; only they can heal it.”

McGuinness says that his work is very much influenced by “sexual politics”. He is “very interested” in the role of women. “I enjoy writing for women and working with women.”

He says it is “inevitable” that sexual politics are going to colour the way you interpret the role of women in a society.

His play Dolly West’s Kitchen is an example of where he “very deliberately made women at the very heart of the play.”

Set in Buncrana in 1943, the play centres around Dolly West who has returned home from Italy before the beginning of WWII. The idea of Irish neutrality is blown apart when Dolly’s mother Rima invites an English soldier (and ex-lover of Dolly) and two American soldiers into the house where Dolly’s brother (a staunch nationalist and junior officer in the Irish army) lives.

“When I wrote ‘Dolly West’s Kitchen’ I wanted to look at the impact of WWII and how it radically altered the characters’ perceptions of themselves and what they do with their lives.”

Death

During the writing of Dolly West’s Kitchen another event occurred that was to have an “enormous impact” on McGuinness and his work. His mother died at the age of 67, leaving him “breathless with shock.”

McGuinness’ loss is evident in the play when Dolly’s mother dies in the second half.

“It was very much part of my grieving process that I incorporated the death of the mother into the play. It’s a terrible shock in the play and it’s a shock that she is not there anymore. That’s parallel to my own experience.”

He continues: “I wrote the death scene in Venice and I think my mother would have liked that. I also wrote that the coffin was carried by Irish, English and American soldiers and I think she would have liked that because she was a remarkably openminded woman.”

Ten months after his mother’s death, McGuinness’ father also died.

“I would have dealt with one death better than the two deaths coming upon each other with such ferocious speed,” he reflects.

“What happens when one of your parents dies is that you become more aware of your own mortality, no matter what age you are. Until you lose a parent there is some part of you that is in denial about the fact that you are going to die. But once you lose someone as close as your mother or father, it registers at every level of your being. Everything changes, everything is different.”

McGuinness’ sadness is evident as he says: “you have also lost an extremely important friend, no matter how you get on with them. The savagery of the grief and the realisation that they are not there anymore to give you advice or to listen; it’s too late. Losing my parents really brought home the finality of death and that takes a lot of stuffing out of you.”

Thirteen years after their death he still misses his parents. “I am still coming to terms with my sorrow. On some level I believe they are still there.”

Creativity

When asked how he writes a play, McGuinness says he begins by doing a “huge amount of research”.

“I think about it an awful lot and take a long time to find what area I am going to work on and who is going to be there. I then try to evolve a plot and piece it together very gently.”

He likens the experience to kindling a fire and says he waits “for a spark to come.”

McGuinness reveals: “I tend that spark until it is built up into a fire. Then I warm myself at that fire and let the heat and hands of the fire move and start to fill the pages. I don’t know where exactly I am going or who will be coming with me.”

He says that his characters are alive as he writes. “They are there with me. I usually enjoy their company or sometimes I am frightened by their company but I have to be with them, nurture them and bring them into being.”

He adds, “I don’t have a formula. I don’t work from 10am to 10pm, I work when I need to but since I stopped smoking eight years ago I can’t work at night. That was a big change.”

McGuinness has to balance the “spark” and creativity of writing a play with his job as lecturer in UCD.

“I like students who really want to read and interrogate the subject, but organising and conducting the lecture really does drain you. It has to be well organised.”

“I like students who really want to read and interrogate the subject, but organising and conducting the lecture really does drain you. It has to be well organised.”